Photojournalism: Pondering the Power of Images and the Risks Taken by Those Who Make Them

James Nachtwey’s book “Inferno” is a collection of 382 photographs depicting the horrific brutality and suffering of people who are entrapped by war, famine or political unrest. Its publication offers an opportunity to reflect not only on his extraordinary and courageous career as a photojournalist but on how, in this time of visual onslaught, images such as these are absorbed and their messages acted upon.

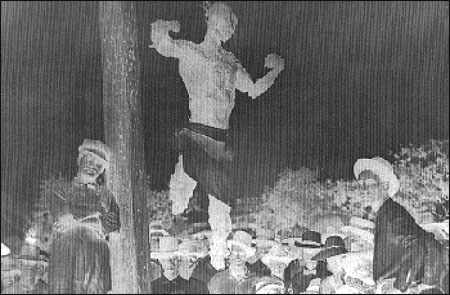

The lynching of Jesse Washington, May 16, 1916, in Robinson, Texas. From the exhibition “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.” Photo courtesy of The New-York Historical Society.

April 9, 2000 The New York Times

Most us have witnessed things that we would be better off never having seen. The writer Susan Sontag applies this distinction to the Holocaust photographs she stumbled upon in a bookstore at the age of 12 in 1945, years before she could conceptualize what the Holocaust even was. Writing of the experience in her landmark book “On Photography,” Ms. Sontag recalled that when she looked at those photographs “Some limit had been reached and not only that of horror…something [in me] went dead; something is still crying.”

The modern era takes it on faith that images of suffering stimulate sensitivity to that suffering. But Ms. Sontag argues that little good comes of viewing photographic horrors that you can barely imagine and have no power to relieve. A few photographs retain their power to shock, becoming moral reference points, she writes. But in general, repeated exposure to photographed horror inures us to that horror, leading us to view even the most grotesque images as “just pictures.”

This warning came immediately to mind recently as I toured The New-York Historical Society’s exhibition “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America,” which opened last month and runs through July 9. The photographs mainly depict black men with hideously elongated necks, swinging sometimes in threes and fours at the end of ropes tied to light poles, trees or gallows. One of the most frightening pictures shows hundreds of well-dressed men in a field, pressing forward for a better view of a naked black man who has just been hanged and is now being mutilated and burned on a pyre.

Like the 12-year-old Susan Sontag in that bookstore, I reached my “limit” quickly and left the room. I returned briefly to take some notes and was on my way, never to return. There is an unbearable measure of horror here that I have no interest in learning to endure.

Lynching scholars tell us that the scenes in this exhibition were repeated thousands of times—often before the entire citizenry of a given town—and were common throughout much of the country until the 1940’s. These “lynching bees” or “Negro barbecues” were often cast as carnivals, to which the residents of nearby towns brought picnic baskets and their children—some of whom are shown in these photographs posed and smiling next to disfigured black corpses. The pictures in this show were mainly postcards that commemorated the “entertainment” and were sent regularly through the mail until it became illegal to do so.

The show opened under the name “Witness” this winter at a small gallery in Manhattan, and consisted mainly of photographs without explanation, mounted on the gallery walls. The Historical Society’s version of the show includes lengthy descriptive captions and an added section on the figures in the anti-lynching movement who eventually brought this horror to an end, among them James Weldon Johnson, W. E. B. Du Bois and the heroine of the movement, Ida Wells-Barnett. Looking at this new section of the exhibition, I was reminded that Ms. Wells-Barnett was sparing in her use of pictures or even illustrations, understanding that likenesses of these events were a form of brutality in themselves. Her first three works on lynching—“Southern Horrors,” “A Red Record” and “Mob Rule in New Orleans”—relied for their power on forensic descriptions of the burnings and lynchings and shared only a single photograph among them.

The Atlanta collector James Allen, who found these photographs, had hoped that they would provoke a discussion on the public nature of racial brutality in the early 20th century and the role that era played in shaping the racial attitudes of today. In particular, Mr. Allen had hoped for a probing inquiry into the nature of what he calls “community violence,” which leads to the bloodlust shown in the pictures. The written material that was added to “Without Sanctuary” has given the exhibition some depth, but not enough to produce the thoughtful meditation Mr. Allen had wished for.

Instead, as he told me recently, “White people feel guilty and reticent; black people look at these pictures and just get angry.” Having worked with these pictures for years, Mr. Allen is less susceptible to their horror and was surprised when I told him that I could not bear seeing them.

A sober inquiry into racial violence has failed to materialize not just in the galleries, but in much of the news coverage as well. Some people were upset when news magazines reprinted the photographs with too little historical context—essentially repeating the acts of those who took and distributed the pictures in the first place. Mr. Allen had hoped to sensitize us to long-buried horrors of America’s racial past. But by choosing to do this through photographs, he chose the most unwieldy method of all. With these horrendous pictures loose in the culture, the ultimate effect could easily be to normalize images that are in fact horrible.

Brent Staples writes editorials on politics and culture for The New York Times and is author of “Parallel Time: Growing Up in Black and White.” Column © 2000 by The New York Times Co. Reprinted by permission.