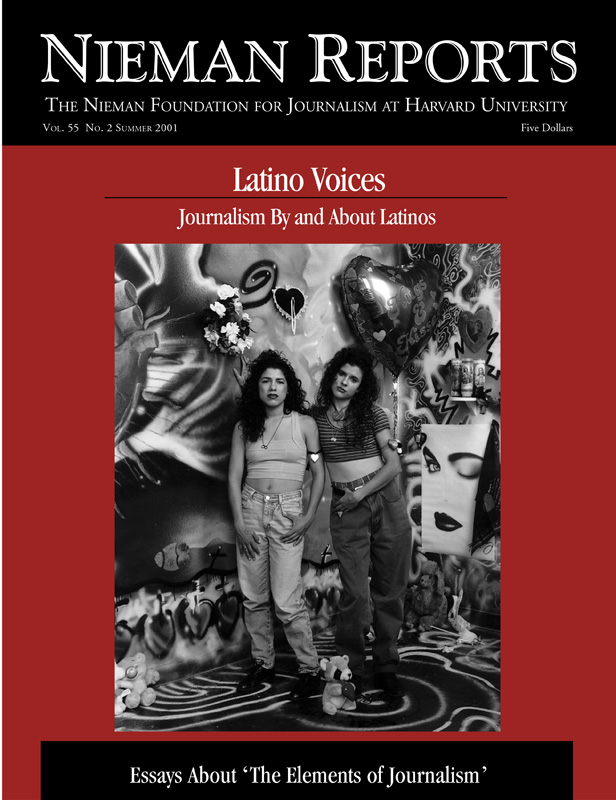

Latino Voices: Journalism By and About Latinos

How is the rapid increase in Hispanic American population affecting communities? What are the economic, social, cultural and educational benefits and hardships brought about by this significant demographic shift? Will the numbers and force of Hispanic voters alter the nation’s political landscape? The questions to be raised and stories to be told vary as greatly as do people portrayed by the word “Hispanic.”

Photo by Alejandra Villa.

I remember my first real job interview. The editor, a debonair man in his late 40’s, pulled off his glasses and looked me in the eye. “Cindy, we normally don’t hire straight out of college, but….”

He had to do something. Latino leaders, small in number but vocal in their demands, were seething mad. For months, they had complained that the only time, it seemed, a Latino appeared in the paper, he was in handcuffs. So after publicizing for weeks an upcoming education forum, these community leaders assumed the Syracuse Herald-Journal would send a reporter to cover it.

The all-day Latino education forum drew people from throughout the city. There were sessions on combating truancy, about bilingual education, and on how students could move from getting mediocre grades to getting all A’s. But the next day, all that appeared in the paper was a photograph of two Puerto Rican teenagers dancing salsa.

Ensuing letters and phone calls spurred editor Timothy Bunn to do something drastic: hire a Latino.

Thus, in May of 1990, I became the first Latino reporter hired at the Syracuse Herald-Journal. That first year was a tough one for a girl raised in Harlem, who was used to big-city surroundings and a diverse array of cultures, living on her own in a city where the word “minority” meant you could practically fit all the city’s Latinos in a couple of high school gymnasiums.

In the newsroom, I was the only and the lonely. My mentors were white. They could help me blossom as a reporter and writer, but when it came to balancing the objectiveness that journalism aspires to with my innate need to see multi-dimensional Latinos portrayed in the paper, I was on my own.

At first, when Latinos complained to me about the barrage of negative stories they saw, I defended the paper. Members of the media don’t create crime in their community; “We just report it,” I’d say. Stories about successful Latinos weren’t as interesting, I explained. “We don’t want to write puff pieces.”

But, in time, I began to see a pattern: For small city newspapers, where local news is everything, defining what’s important news came from the top. The problem was that the top people knew hardly anything about Latino culture, nor did they have any meaningful contact with Latinos (aside from the occasional obligatory meetings with leaders).

So I came to the scary realization that if the newspaper was going to make inroads in the community, the responsibility was pretty much on my shoulders.

When I was growing up, I created family newspapers on sheets of loose-leaf paper. All I dreamt of was becoming a gritty newspaper reporter. I wanted to be like Jimmy Breslin, like Pete Hamill. But now that I was a reporter, I realized I couldn’t just focus on becoming a better writer. Instead, in trying to mesh who I was with the job I needed to do, I was about to be labeled by people on polar-opposite sides.

When I wrote hard-hitting stories exposing a problem in the Latino community, members of that community considered me disloyal, while editors praised me. When I wrote profiles about successful Latinos, colleagues said I was not being objective, but Latinos applauded. If I complained about the lack of other Latinos in the newsroom, I was a malcontent. Of course, I also had to prove myself more than other reporters for it was assumed that because I am Latina I was therefore: a) a token, and b) incompetent.

I came into journalism during a time when newspapers hired reporters of color in an attempt to have their staff mirror the communities they covered, when newspapers spent money on “diversity training,” when retention of journalists of color sometimes meant promoting someone earlier than might otherwise be the case. Those noble efforts have died. With some notable exceptions, newspapers just got tired of the effort. I’ve visited many big-city newsrooms to see friends, so I know what I’m talking about when I say many have a bare minimum of minorities. But among all minorities, Latinos usually number the fewest, even in cities where there are sizeable Latino communities.

My own newsroom is testament to that. At The Boston Globe, I am the only Latino reporter on a metro desk of about 50. There are no Latinos on the business desk. No Latino feature or entertainment writers. No Latino editorial writers or columnists. No Latino page designers. No Latinos on the news copydesk. None in upper management. Our highest-ranking Latino is assistant city editor—a first in that job. We have a Latina education editor, a Latino reporter covering New Hampshire, a Latino photographer, sportswriter, graphics artist, and a Latino on the sports copy desk. Our Latin America correspondent is Latino.

I can count all of us on two hands, and that’s in a newsroom with more than 400 people. We account for less than three percent of the staff in a city that is 14.4 percent Latino and within a county that is 15.5 percent Latino.

It’s troubling to me and to some of the other Latino staffers. But if we speak up—or dare write about it in a publication such as this one—we’re considered traitors.

Latino journalists, like other minorities and women, have long debated the question: Should I focus on work and not worry about this? For the most part, we do. But for minorities who see problems that arise from not having a diverse staff—chiefly the lack of meaningful coverage to take readers beyond coverage of crime and Latino baseball stars—it’s clear that problems ignored continue to gnaw at us.

So we speak up at times. We offer the name of a qualified candidate, suggest stories to other sections of the paper. But it’s tiring. We field calls from politicians, artists, promoters, Spanish-language media, all hoping that because they called a Latino reporter they can get their news in the paper. But since we’re limited in time and in what we can do on our beats, worthy stories end up getting no ink.

Little by little, we withdraw. After all, it’s hard to feel invested in a newspaper, a radio station, a television news program that doesn’t invest time and resources in understanding your community and conveying news from it.

Most marketing experts would just rather ignore us as readers, listeners and viewers. The reasoning is that the median household income of Latinos is too low to serve as an attraction for most big advertisers. What this bit of information overlooks, of course, is that to arrive at the median, wealthy and middle-class professionals are put together with newly arrived, poorer immigrants, bringing the average down to a lower figure.

If the patterns of the past few decades don’t change at media outlets, the revolving door of Latino journalists in American newsrooms will continue, guaranteeing that we’ll have the minimum number of Latino staffers and minimum coverage of Latino issues, culture, arts and music. And all over the country, there will be plenty of Latino journalists just like me: either the only or the lonely.

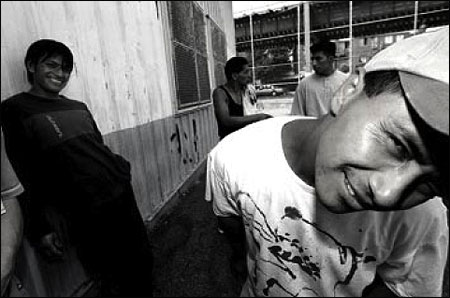

Photo by Alejandra Villa.

Cindy Rodríguez reports on immigration issues and is the chief 2000 Census reporter at The Boston Globe.