Trauma in the Aftermath

Reporting in the aftermath of tragedy and violence, journalists discover what happens when people survive crippling moments of horror. Pushing past what is formulaic and numbing, they find ways to craft stories where the touch is raw and real. In this issue of Nieman Reports, journalists are joined by trauma researchers and survivors themselves in telling their stories in their own voices. We invite you to listen in.

One of 400 boxes of files recovered in 2003 from the basement of 50 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City. The building housed The Associated Press from 1938 to 2004. Photograph by Valerie Komor/Courtesy of AP Corporate Archives.

Newspapers, once treated like members of the family, welcomed at breakfast tables and at Sunday brunch, are increasingly estranged. In Denver, the venerable Rocky Mountain News has ceased publication. In Seattle, the Post-Intelligencer has gone, replaced online by a shadow of its former self, although no one knows how long that will last. As months and years roll by, more newspapers surely will disappear.

This realization leads us to raise a related issue: Who, if anyone, is going to save our newspapers’ archives? With each closure or merger, new ownership or online experiment, archival records are imperiled. News librarians, who are typically custodians of “the morgue” and the digital text files, are often among the first to be laid off as ailing papers cut staff. When the last tear is shed and the lights turned off in a just-laid-to-rest newsroom, little is likely to be done to save what’s been filed away. Lost, as a result, will be the back story to the first draft of a community’s history.

Local news media are to their communities—and national media are to the nation—what mortar is to bricks. We chiefly think of this as the impact daily news reporting has on citizens’ conversations about politics, sports, business or whatever matters to them. “To read a newspaper is to know what town you’re in,” Michael Sokolove observed in his August 2009 New York Times Magazine article, “What’s a Big City Without a Newspaper?”

In this vein, it’s reassuring to know that every back issue of the Rocky Mountain News is housed at the Denver Public Library, long a renowned repository for historical Colorado newspapers. But past issues of a newspaper are not the only things worth preserving. The company records are important as well—and for similar reasons. Such files—archivists describe them as “corporate archives”—document a newspaper’s history in financial and legal records, through editorial memoranda and correspondence, photographs and other materials. In reading these, we can learn how the paper developed and organized itself, how editors and reporters approached stories, and how community leaders and ordinary citizens responded to them.

To read the behind-the-scenes story of a newspaper in these files is to peek behind the curtain and see the bumps and bruises, along with the joy and anguish, of our community conversation.

News Archives

Allan Nevins, a leading historian of his day who had a special interest in the press, placed a high value on newspaper archives. In 1956 he made a suggestion over lunch with Arthur Sulzberger and some editors at The New York Times. “I called their attention to the value of an archive preserving confidential materials,” Nevins recalled in a speech several years later. “Mr. Sulzberger then and there gave instructions to have such an archive formed; but whether these directions were ever carried out I do not know.”

RELATED ARTICLE

Steven A. Smith wrote about "Black and White and Dead All Over" in his article "If Murder Is Metaphor," from the Winter 2008 issue of Nieman reports.Sulzberger’s wishes were, in fact, realized. Before the Times moved to its new quarters on Eighth Avenue in 2007, one could consult a vast collection of files in the basement of the old building on 43rd Street—a dark ink-stained cavern that is central to a recent hilarious roman à clef mystery by Times reporter John Darnton, “Black and White and Dead All Over.” In June 2007, the Times donated a large portion of this material—78 linear feet in all—to the New York Public Library, where the now-titled Adolph S. Ochs Papers (1853-2006) have since been catalogued by archivists.

RELATED ARTICLE

John Maxwell Hamilton previously wrote "Afghanistan-ism:An Apt Metaphor for Foreign News Reporting" in the Fall 2009 Nieman Reports.Other troves of material have been similarly saved. The Newberry Library in Chicago has an extraordinary collection of the personal and business papers of Chicago Daily News journalists, thanks to the generosity of newspaper owners and their heirs in Chicago through the years. In 2006, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded the Newberry funding to preserve 39 discrete journalism collections and make them accessible. The archivists there, led by Martha Briggs, have largely completed their work. As one of us learned while conducting research in these collections for the book, “Journalism’s Roving Eye: A History of American Foreign Reporting,” the Daily News is more responsible for creating modern American journalism than any other newspaper—a story that has never been told in full, but now can be.

Two of those with papers at the Newberry—Melville Stone, who created the Chicago Daily News, and Victor Lawson, who took the paper to the heights of journalism—were leaders in establishing the modern Associated Press. Stone became the general manager of The Associated Press (AP) of Illinois in 1893. Lawson served as The AP’s president from 1894 to 1900, the year The AP moved to New York, where the corporation laws were more favorable to cooperatives. AP records piled up over the next century. When Tom Curley became its president and CEO in 2003, thousands of documents lay unattended in filing cabinets in the basement of The AP’s headquarters at 50 Rockefeller Plaza. As one of his first decisions, Curley arranged for this trove to be preserved, organized and made available to researchers—and an archivist (the author, Valerie Komor) was hired in 2003 to oversee this effort.

Minutes from a 1945 meeting of the AP board—found among the materials retrieved from storage—reveal how easily material can be lost without such foresight. By that time, AP’s offices had simply run out of space, forcing an unpleasant choice on the board, which it acknowledged, while announcing its drastic solution: "To secure needed storage room, segregation had been made in the files covering the first 20 years, namely the files of the Illinois Corporation 1893-1900 and of the New York Corporation from 1900-1913. From these early files all the corporate records had been segregated. The Board approved the preservation of the segregated corporate records, and directed that the balance of the old files be destroyed."

What a pity—and a reminder that for every successful instance of archival preservation, there are many more failures. Here is another. When James Hoge Jr. was the publisher of the (New York) Daily News, he directed staff to send the corporate archives to the library at Princeton University for preservation. It never happened. The corporate records of the Rocky Mountain News (financial, legal, human resou

rces, and other executive records) have gone to the Scripps headquarters offices in Cincinnati; let’s hope they are preserved and maintained by an archivist and eventually made available to researchers.

Think of your favorite dead newspaper and see what you can find looking at WorldCat, the largest online union catalog of research library holdings. Here are some hints:

- Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library holds the records (95 linear feet) of the New York World.

- Temple University holds a complete run of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin as well as the papers of Bulletin editors and reporters. (When newspapers were owned by individuals, not large corporations, personal files were virtually corporate files.)

- There is no archive with records from the New York Herald, though the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress hold relatively small collections of the papers of Herald founder James Gordon Bennett.

The same uneven pattern applies to broadcasting:

- Splendid NBC corporate records can be found at the Library of Congress and the Wisconsin State Historical Society, which has one of the best collections of journalists’ papers anywhere. (NBC also sent broadcast discs—150,000 16-inch lacquer discs spanning the years 1935 to 1971—to the Library of Congress’s Recorded Sound section.)

- To our knowledge, no centralized collection of CBS corporate archives exists, although each CBS department maintains its own files. Over the years, individual CBS journalists (many with Texas connections) have given their papers to the University of Texas at Austin, as the late Walter Cronkite has done. Today, the university’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History holds an impressive number of collections of CBS broadcasters, and they have just added to their photojournalism collections with the Eddie Adams archive.

- Local broadcasting records are even harder to find. They are difficult to preserve because the materials produced are generally too costly and voluminous for a single institution to care for long term.

View larger image »

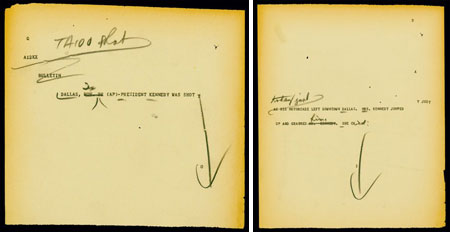

The first two sheets of “A” wire copy announcing the shooting of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963 were edited in pencil before being distributed worldwide. Kennedy Wire Copy Collection/Courtesy of AP Corporate Archives.

Path Toward Preservation

So what is to be done to follow Nevins’ advice on a large, systematic scale? No simple one-size-fits-all answer exists, but some approaches suggest themselves as potential partial solutions. An obvious first step—to set into motion a range of solutions—is to put preservation of archival records high on journalists’ agenda. (Though the desire to do this is already high on the agenda of librarians and archivists at both local and national levels, their voices are unlikely to have the force necessary to make this happen.)

Although the accelerating rate in the demise of newspapers and other traditional news media drives our concerns about creating such archives, the best place to start is with healthy media operations, as happened with the Times, The AP, and NBC. Thoughtful approaches there led to preserving materials in an orderly way and to long-term planning for their use and safe disposition. Thus, owners, corporate executives, and editors need to be educated on why this is important.

Such discussions should be on the meeting agenda of the Newspaper Association of America, made up of publishers and owners, and the broadcast equivalent, the National Association of Broadcasters. Ditto for the American Society of News Editors, and the Radio Television Digital News Association (formerly the Radio Television News Directors Association). A few industry leaders—Belo Corporation, for instance, which donated its print and broadcast archives to Southern Methodist University this fall—could lead the way in such discussion. Meanwhile, archivists at the state and local level can be active in their own educational outreach by approaching local media executives.

When demise is imminent—and such planning has not taken place—more urgent steps need to be taken. It would help if national organizations such as the National Endowment for the Humanities or foundations such as Knight, Pew or even Mellon had emergency funds to help save these valuable files.

One promising idea comes from Bernard Reilly, president of the Center for Research Libraries in Chicago. “The historical record of our society that major newspapers create and maintain is a public good,” he says. “So, would it be possible, for example, to write into the federal tax code incentives for media organizations to provide for their archives?” He is envisioning the government giving full market-value deductibility as donations for making investments in the maintenance of back files.

Something else would help too. While it is important to work on the supply side of preservation, much more can be done to improve the demand side. Many historians are not aware of what is available. This is because the materials that have been preserved are spread out in libraries and archives across the country and not always found in logical places. Why, for instance, would the papers of Negley Farson, one of the great Chicago Daily News correspondents, be at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center? Farson traveled widely in his journalism career, but Wyoming held no particular importance in his career as far as his various memoirs relate.

Almost 20 years ago the Freedom Forum published “Untapped Sources: America’s Newspaper Archives and Histories.” This slim publication was not close to complete then and is entirely out of date today. But it remains useful because nothing else exists. The Library of Congress or the Newseum, created by the Freedom Forum, could build on this concept by developing and maintaining an up-to-date and thorough online listing. By letting historians know where these records reside, collections will receive greater use. In turn, this will make it easier to argue for the value of preserving the colorful, meaningful histories that lie in the files of our news organizations. After all, the experiences

and insights contained in their files collectively constitute one of our country’s vital contributions to the workings of a functioning democracy.

John Maxwell Hamilton is Hopkins P. Breazeale professor and dean at the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University. In 2003, Valerie Komor became the founding director of The Associated Press’s Corporate Archives.