While covering Hillary Clinton’s New York senate race for The Associated Press, I happened to read “The Boys on the Bus,” Timothy Crouse’s classic tale of reporters on the McGovern-Nixon campaign trail. Although nearly 30 years had passed since the 1972 presidential race, many aspects of campaign coverage remained unchanged—bad food, silly songs, inside jokes, and speeches we knew by heart.

But there was one big difference. Crouse and his colleagues were nearly all men. When I covered Hillary Clinton, my colleagues were predominantly female. Of course there were exceptions, notably correspondents for New York City’s major dailies, The New York Times, Daily News and New York Post. But they were outnumbered by women from AP, Reuters, Gannett’s suburban daily The Journal News, The New York Observer, Newsday, USA Today, an ABC producer, the WCBS-TV and WCBS radio correspondents, and crews from a local news cable channel, NY1.

Throw in a few female photographers, three out of Clinton’s four press aides, her personal assistants, and female TV correspondents from around the globe (who were always interrupting press conferences about taxes with questions like, “Hillary! What is your message for the women of Italy?”) and I felt like I was back in my all-girl high school. Only instead of giggling with my friends in the stairwell, I was sharing stories about my kids with the other working moms on the minivan that drove us from one campaign stop to another.

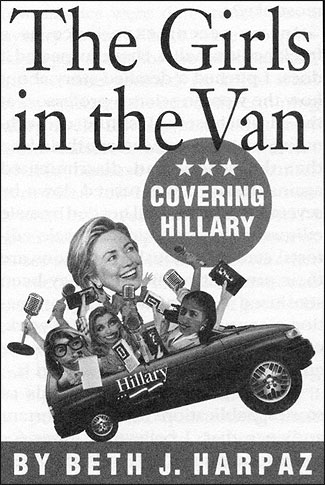

We were no longer the boys on the bus. We were the girls in the van.

How did that make things different? Well, for one thing, if campaign events ran later than scheduled, those of us with kids had to make emergency calls to babysitters and pay late fines to day-care centers. Some evenings I finished dictating my story by cell phone while pushing the stroller home; other nights I relied on campaign staffers (Clinton’s or her opponents’) to call with an update on an event I couldn’t make without upending a complicated routine of homework, bedtime stories, and baths.

Still, I worried that any small kindness the campaign showed towards my children might compromise my integrity. When Clinton surprised me with a copy of her book, “Dear Socks, Dear Buddy,” inscribed to my boys, I sweated buckets worrying that it was an ethical lapse to take her gift. I immediately turned it over to my boss. But it turned out that The A.P. deems a copy of a book from an author to be a token gift, like a cup of coffee, and therefore not a conflict of interest. (I later sent Clinton a copy of my book about the campaign, so I figure we’re even.)

One day when I had to pick my kids up on time, I got word that Clinton was about to release a new campaign ad. The candidate had a favorite phrase to explain some of the choices she makes politically—“conflicting values”—so I e-mailed her press secretary to ask when the ad would be ready and added, “I’m probably walking out the door at four-thirty, so if I need to plan a stop at your office on my way home, I need to know. Sorry, but it’s the old conflicting values dilemma. Hillary on one hand. Seven-year-old Danny and two-year-old Nathaniel on the other.”

Two minutes later, the press secretary e-mailed me back. “Release is going out now. Ads should be available at the office presently. I vote for the kids, by the way.”

Was I wrong to push for the timely release of the ad because I needed to get home? Was I abusing my working mother status? Or was I merely asking for a small scheduling accommodation that might be requested by any reporter, male or female, who had a doctor’s appointment or tickets to a World Series game? This was the kind of question I struggled with daily and hoped that, on balance, my dilemmas were not all that different from anyone else’s.

By the way, I can confidently report that cynicism—the disease that overtakes most political reporters when they watch a candidate up close day after day—is gender-blind. My male and female colleagues were equally prone, when deconstructing campaign developments on the van, to dismiss some new issue promoted by either candidate with an eight-letter word that begins with a noun for a male cow. And both the boys on the bus and girls in the van became very good at aping the first lady’s distinctive way of saying “Thank you so-o-o-o-o much!” or doing skits about some of the subjects that turned up repeatedly in her speeches. (Her obsessions ranged from the human genome to Harriet Tubman.) Most if not all of us refrained from voting in the election, a point of pride for many political reporters who want to be able to say that they do not weigh in with their opinions on the campaigns they cover.

Anna Quindlen, one of the only female reporters to cover city hall when she worked for The New York Times, once wrote that she’d had “years of worrying that the best stories were coming out of conversations in the men’s room.” So it was only fitting that on the first leg of Hillary’s famous “Listening Tour” in upstate New York, a couple of male reporters goaded (Albany) Times Union correspondent Lara Jakes into going after Clinton at a rest stop. Carrying a tape recorder, Lara gamely followed the first lady and an aide into the ladies’ room. “I’m not gonna ambush you in the bathroom,” she said in response to their glares. “I’m just gonna make sure no news happens.”

When Lara got back on the press bus, she wondered if she’d let down her colleagues. “They send me in here to the bathroom and I don’t know if I’m supposed to ask her about Whitewater or what,” she recalled. “…I just don’t really feel comfortable asking her questions in the ladies’ room. I kept thinking, ‘What would a guy do?’”

Despite several other bathroom encounters between Clinton and reporters, I don’t believe anyone ever got a scoop over the sound of flushing toilets. For that matter, I don’t know of any big stories that Mayor Rudolph Giuliani passed on in the men’s room. Nor do I imagine his top press aide, a woman named Sunny Mindel, giving away secrets in the ladies’ room.

But it’s not only access to gender-segregated facilities and work-family juggling acts that are different now; sometimes it’s also the substance of the conversation.

In “Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail 72,” Hunter S. Thompson relates how he got to ride alone with Richard Nixon. There was just one catch: He could only talk about football. I fondly recall my equivalent: the day Clinton asked how my vacation was, and I unthinkingly responded, “It was great! I potty trained my two-year-old.”

The first lady looked at me as if she hadn’t heard me right. “You did what?” she said.

I suddenly realized I should have said something more conventional about my vacation, like “It was so relaxing.” Too late! I repeated the potty training line in a tiny voice, wishing I could disappear.

“You potty trained your two-year-old?” Clinton echoed, as if she couldn’t believe her ears.

I nodded, feeling humiliated. But I needn’t have worried. All of a sudden Clinton looked around at the other reporters and campaign workers and boomed, “This woman deserves a round of applause!”

Apparently when both candidate and reporter are female, a conversation about potty training is no less appropriate than a conversation about the Super Bowl—especially when the candidate’s platform includes not support for the construction of new stadiums but support for child welfare and working families.

That night, the WCBS-TV news broadcast led with a segment on Clinton’s new comfort level with the press corps. The segment included a tape of our conversation about potty training. Unbeknownst to me, the cameras had been rolling, and the station’s correspondent—of course, a woman—deemed it worthy of the 11 o’clock news.

Beth J. Harpaz is on leave from her job as a reporter for The Associated Press, which she joined in 1988 after working for the Staten Island Advance and The Record of Hackensack, New Jersey. She has won feature-writing awards from the New York Press Club and The Newswomen’s Club of New York. Her book, “The Girls in the Van: Covering Hillary” (St. Martin’s Press), chronicles Hillary Clinton’s senate campaign, which Harpaz covered for The A.P. Her second book, “Finding Annie Farrell,” the true story of five sisters from Maine, is due out in 2003.