Covering Indian Country

As a young reporter at The Rapid City Journal, Tim Giago was seldom allowed to cover stories on the nearby Pine Ridge Indian Reservation where he was raised. As one editor told him, being Native American meant he could not be objective in his reporting. In 1981 he moved back to the reservation to start a community newspaper called the Lakota Times. At that time it was the only independently owned weekly Indian publication in the United States. In this collection of stories, Native Americans and non-natives who tell stories about the lives of Indian peoples talk about their obligation to fairness and the skills they need to live up to this responsibility.

No education in tribal government compares to the one I’ve had during the 29 years and 11 months I worked as reporter and editor for the Wotanin Wowapi, my tribal newspaper. As I look back, I see that the path I walked was one that has been taken by no other nonelected person among our 10,000-member tribe. The path led me into the hallowed chambers of our tribal government and, once there, I watched and learned what was going on among our elected leadership. Most importantly, I became the first person to report what I saw and heard to our people.

My reporting journey started in March 1976 when I dropped out of Haskell Indian Junior College in Lawrence, Kansas—the only all-Indian junior college in the nation—three months short of graduating with an associate’s degree in general studies. When I returned to the Fort Peck Reservation, home to several bands of the Assiniboine and Sioux nations in northeastern Montana, I got a job as a reporter for our tribes’ biweekly newspaper only because, by chance, I’d signed up for a journalism class that I never completed.

The Wotanin newspaper had been started in the winter of 1970 by a group of young people sent to our reservation by Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), a program started in the 1960’s to send young service volunteers to disadvantaged urban and rural areas of America. In the beginning, it was a four-to-six page biweekly newsletter copied onto legal-sized paper out of an office in the tribal offices in Poplar.

On its pages was printed the log of actions passed by the tribal council. Never before had there been such a tribal publication available to the Indian people to read about actions taken by their government. But what they learned was only what happened, not how it had happened or what it meant to them. Nor did the items go into detail about who had initiated it or who had supported it. Slowly the Wotanin evolved into a tabloid-sized newsletter that contained a few of the community happenings on the reservation, some sports activities, and some major national news of interest to Indian people. Still, coverage of our tribal government was scant.

By the time I went to work as a reporter, the Wotanin’s editor was taking tiny steps into tribal government coverage by publishing stories about major issues affecting the Fort Peck Tribes. To augment this, he placed me in the council chambers with instructions to write down all that took place during the council’s deliberations. This was one of the first major steps taken by the Wotanin to become a watchdog of tribal government on the Fort Peck Reservation.

Watchdog Reporting

I was serious, and I took my editor’s instructions seriously. Never mind that I was being paid by a federal trainee program that could end abruptly once the money allocated for my position was depleted. I took the plunge and learned to swim. From that point on, I sat in on every biweekly council meeting of our tribes’ government, and I also started sitting in on the committee meetings, since all of the council’s actions started at committee level before being taken to the full council for ratification. The more I listened, the more I learned. And the more I learned, the more I wrote down, and the more I was able to comprehend what was happening. It was an invaluable lesson in how this tribal government worked, a lesson not many people have ever had.

I covered in great detail the committee meetings, where policies and actions that affect our tribes are initiated. Using my own-fashioned speedwriting, I jotted down everything that was said and done, including who wanted what and why. Most importantly, I wrote down the positions that our elected officials took on all the issues that were going to be presented to the full council for action. In the Fort Peck Tribes’ form of government, each of the 12 council members sit on one committee each day, and this is where they discuss the actions they plan to take. Soon I began to draft stories before the full council would meet in which I wrote about issues that were going to be addressed at those meetings. And once an issue got to the full council, I wrote a story on the decision-making and the final outcome.

Tribal Leaders Respond

After one year of being a reporter, I was appointed to the job of acting editor while the paper’s editor went on leave to farm. Only then did I become aware of the anxiety my reporting of tribal government was causing the tribal council. I can recall the first time I was called before one of the committees. At that time, the council’s members were what can be described as “old school.” Some believed that the official actions they took were based on the number of votes these actions would get them in an upcoming election and not based on what was good for the people as a whole. Reporting how they voted—who was for or against an issue and what they said in their discussions—and putting this all into print for community members to read was a totally new experience for them and for our readers.

The newspaper staff accompanied me to the council chamber that day. I didn’t know what to expect since this event was another first in our tribes’ history. The members of the council told me that tribal members living off the reservation (who received the Wotanin by mail) were calling some of them to ask what was going on at home and expressing concern about news they were reading, not all of which was positive.

“OK,” I said in response.

In different ways, they kept asking me why I was doing these stories. Very calmly, and as respectfully as I could because I was speaking to our elected officials, I told them, “I’m not creating this news. I’m only reporting what you’re doing. I’m only doing my job.” As they wrung their hands in frustration, and after a few more comments they made among themselves about how bad the Wotanin was making some of them look, we were excused and told to return to work.

The council’s next move was to create a board of directors for the Wotanin. They picked an all-male group of tribal employees and one elected official to serve on this board. I was called to their first organizational meeting and informed of their existence. I didn’t like it, but I was cordial. I asked the council politely, “What is the role of this board? Will you be looking over and deciding what news goes to print?”

“Yes,” the chairman of the Wotanin’s new board of directors responded.

I took a photograph of the board members and published the picture on the next issue’s front page. Along with the photo, I published a short article explaining that the tribal council had named a board, the purpose of which was to begin censoring the news.

The reaction from our readership was swift. They did not favor any censorship of the news, and they let their elected officials know. Other news outlets that subscribed to or exchanged news with us—such as a television station in Williston, North Dakota, some 70 miles to the east of the Fort Peck Reservation and one of the first national Indian newspapers, the Wassaja—also reacted to this article with more coverage of what was happening.

Public pressure stopped the censorship, but not the council’s attempt to stop our tribal newspaper’s coverage of our elected government. The next thing they did was advertise the position of editor. I’d been named “acting” editor in the summer of 1976 and was still working in that capacity in 1977. One day I was stopped on the street and asked whether I was resigning, since the position was being advertised in the Poplar Shopper, a non-Indian weekly newspaper that only covered the happenings in that community. For some reason, the board of directors did not advertise it in the reservationwide Wotanin Wowapi. I applied for the position and was eventually selected and voted in by a majority of the council.

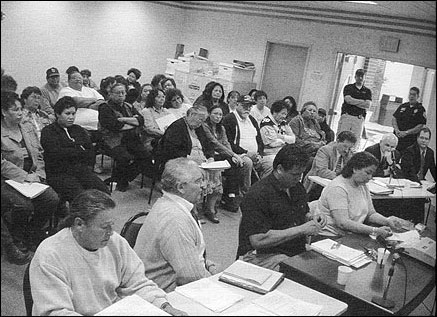

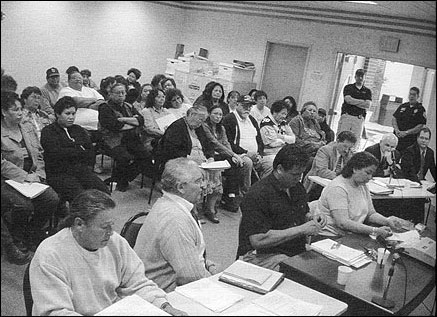

There was tension in the tribal council chambers when John Morales was removed as Fort Peck tribal chairman. June 2004. Photo by Louis Montclair.

The Paper’s Commitment

From that time forward, I became accepted by the council, the tribal employees and those who staffed their programs, and the community in general. I continued to attend most of the committee meetings and all of the tribal council meetings. In the newspaper I created a format in which to report all statements and actions made by our elected officials, our programs and employees, including federal employees who worked for agencies that were there to serve our people, such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service.

I did not back away from controversy. Soon employees—who had insight into situations that were not right and needed to be brought to light in the newspaper—brought issues to my attention. These were situations not readily visible to people who didn’t keep the books or were not aware of what happened in some of the meetings, such as those held by various boards of directors. One tribal chairman had himself appointed to a board of directors of a tribal industry without following policy. He eventually took himself off that board and let the process move ahead in the proper way, but this only happened after I disclosed the irregularities in a front page story placed above the fold.

I approached my job strictly from the perspective of a journalist, without animus toward those on whom I reported. To my surprise, so did the council chairman who never seemed to hold a personal grudge against me and was always forthright in any interviews I did with him during the more than two decades he served on the council after serving one term as a chairman.

During the 1970’s and 80’s, there was strong support in the community for freedom of the press as I faithfully and happily covered our tribal government and its programs. Often I stayed up late into the night, typing with great detail each bit of news about the actions of our tribal council. Sometimes my minutes of the meetings took up two to four full newspaper pages, which is what people wanted and expected.

The process seemed to be smooth and, as time went by, people began to share with me all kinds of information that was being provided to our elected officials. At each full meeting of our government, the chairman’s office would provide each of the 12 council members a packet of correspondence received by his office, including memos and opinions from our tribes’ attorneys, travel requests, committee minutes, and any correspondence related to committee business, even copies of who was approved for enrollment in our Fort Peck Tribes. At each council meeting a packet was set aside for me, with my name on it, and I wrote stories about most of what I learned from reading its contents. If the matter was of interest to our tribal membership, I would use the letters or documents provided to me and make calls to add information to these stories.

One longtime tribal official, who served 50 years on the council and died while in office, understood and was supportive of freedom of the press. He served on the council and was also tribal chairman and was a strong leader who was well known on the local, state and national levels of government. He was the person who told the council that it should be OK for me to sit in on closed-door discussions between them and the tribes’ attorneys on a variety of important issues such as water rights, gaming, taxation and even personal issues such as the holding of incapacitated persons for treatment. He explained that in doing so I’d gain a good background when it came time to report on these issues. And it became quite a learning experience, one in which I gained a lot of knowledge about an issue’s historical perspective. Soon I was invited to travel with the council on some of their more important delegations so that I could see first hand what they were doing and report on it, which I did.

One October a young, rambunctious, popular man was elected to serve on the council. Eventually he came to frown on the Wotanin’s reports of some of the council’s actions, particularly when the stories involved him. Council members who also wanted to return to how things used to be quickly joined his side in what was becoming an uncomfortable confrontation. I was not willing to stop my reporting, so this councilman began writing his side of the story, while also trying to cut down the Wotanin. We published his words in the opinion section and let him have his say. He was eventually able to get some of the tribes’ funding of the newspaper cut, and he became someone who stood in opposition to freedom of the press on the reservation.

Several years later, when he was no longer on the council, he attended a Native American Journalists Association conference and saw and heard the efforts of the Wotanin lauded by other tribal press. Later, when he came back to the Fort Peck Reservation and ran again for tribal office, he came to the newspaper and apologized for his earlier actions. By then, however, inroads he’d made against the paper were being rejoined. In 2000, the tribal chairman was convinced by others to stop providing copies of committee minutes to the newspaper until the day of the full council meeting. (The only way we could find out what the committees were doing was to sit in on the meetings, but we were not able to sit in on every one of them. If we did, there would not be any other type of news in the paper.) Because of this change, we lost our edge in getting word out to the people what the council would be considering at their next meeting. Information, in general, provided to the press dwindled after that. By 2001, the press packet included only copies of committee minutes and the travel log.

The councils that were elected in 2001, 2003 and 2005 have used in many instances the “executive session” rule in Robert’s Rules of Order in conducting their meetings. In an effort to keep some issues out of the public eye, the majority of the elected officials have voted for closed sessions, thus keeping the press out. This means that the people do not learn what has gone into the decisions their tribal leaders are making.

In February 2005, what I saw as the final blow to the press occurred when the tribes’ “random” drug-testing policy was leveled on the four-member staff of the paper, all at the same time. I refused to abide by it because this testing was anything but random. As a result, I was fired from my job as editor. I didn’t take this matter to the people, as I had in the past. Nor did I file a grievance, which I had a right to do. I walked away in an act of defiance.

My termination did not mean the end of the paper. At the Wotanin, I had four freelance reporters who had their own beats to cover. One of them stepped forward and is acting editor. But my departure ended a lot of tribal council coverage, since that was my beat.

The Wotanin was my baby. I raised it, along with my four children. I took it from a tabloid-sized biweekly newspaper to a weekly full-sized paper that was bursting with news of our people. Each year our dependence on tribal monies to operate grew less and less, while the advertising and revenue from newspaper sales grew. Today, wherever I go, I come across people who tell me they miss me at the paper. I miss it, too.

Bonnie Red Elk, a Lakota-Dakota, served the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes as reporter/editor for nearly 30 years. The Native American Press Association presented her with two awards for Best Coverage of Tribal Government. She now freelances for the local non-Indian weekly newspaper on the Fort Peck Reservation.

My reporting journey started in March 1976 when I dropped out of Haskell Indian Junior College in Lawrence, Kansas—the only all-Indian junior college in the nation—three months short of graduating with an associate’s degree in general studies. When I returned to the Fort Peck Reservation, home to several bands of the Assiniboine and Sioux nations in northeastern Montana, I got a job as a reporter for our tribes’ biweekly newspaper only because, by chance, I’d signed up for a journalism class that I never completed.

The Wotanin newspaper had been started in the winter of 1970 by a group of young people sent to our reservation by Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), a program started in the 1960’s to send young service volunteers to disadvantaged urban and rural areas of America. In the beginning, it was a four-to-six page biweekly newsletter copied onto legal-sized paper out of an office in the tribal offices in Poplar.

On its pages was printed the log of actions passed by the tribal council. Never before had there been such a tribal publication available to the Indian people to read about actions taken by their government. But what they learned was only what happened, not how it had happened or what it meant to them. Nor did the items go into detail about who had initiated it or who had supported it. Slowly the Wotanin evolved into a tabloid-sized newsletter that contained a few of the community happenings on the reservation, some sports activities, and some major national news of interest to Indian people. Still, coverage of our tribal government was scant.

By the time I went to work as a reporter, the Wotanin’s editor was taking tiny steps into tribal government coverage by publishing stories about major issues affecting the Fort Peck Tribes. To augment this, he placed me in the council chambers with instructions to write down all that took place during the council’s deliberations. This was one of the first major steps taken by the Wotanin to become a watchdog of tribal government on the Fort Peck Reservation.

Watchdog Reporting

I was serious, and I took my editor’s instructions seriously. Never mind that I was being paid by a federal trainee program that could end abruptly once the money allocated for my position was depleted. I took the plunge and learned to swim. From that point on, I sat in on every biweekly council meeting of our tribes’ government, and I also started sitting in on the committee meetings, since all of the council’s actions started at committee level before being taken to the full council for ratification. The more I listened, the more I learned. And the more I learned, the more I wrote down, and the more I was able to comprehend what was happening. It was an invaluable lesson in how this tribal government worked, a lesson not many people have ever had.

I covered in great detail the committee meetings, where policies and actions that affect our tribes are initiated. Using my own-fashioned speedwriting, I jotted down everything that was said and done, including who wanted what and why. Most importantly, I wrote down the positions that our elected officials took on all the issues that were going to be presented to the full council for action. In the Fort Peck Tribes’ form of government, each of the 12 council members sit on one committee each day, and this is where they discuss the actions they plan to take. Soon I began to draft stories before the full council would meet in which I wrote about issues that were going to be addressed at those meetings. And once an issue got to the full council, I wrote a story on the decision-making and the final outcome.

Tribal Leaders Respond

After one year of being a reporter, I was appointed to the job of acting editor while the paper’s editor went on leave to farm. Only then did I become aware of the anxiety my reporting of tribal government was causing the tribal council. I can recall the first time I was called before one of the committees. At that time, the council’s members were what can be described as “old school.” Some believed that the official actions they took were based on the number of votes these actions would get them in an upcoming election and not based on what was good for the people as a whole. Reporting how they voted—who was for or against an issue and what they said in their discussions—and putting this all into print for community members to read was a totally new experience for them and for our readers.

The newspaper staff accompanied me to the council chamber that day. I didn’t know what to expect since this event was another first in our tribes’ history. The members of the council told me that tribal members living off the reservation (who received the Wotanin by mail) were calling some of them to ask what was going on at home and expressing concern about news they were reading, not all of which was positive.

“OK,” I said in response.

In different ways, they kept asking me why I was doing these stories. Very calmly, and as respectfully as I could because I was speaking to our elected officials, I told them, “I’m not creating this news. I’m only reporting what you’re doing. I’m only doing my job.” As they wrung their hands in frustration, and after a few more comments they made among themselves about how bad the Wotanin was making some of them look, we were excused and told to return to work.

The council’s next move was to create a board of directors for the Wotanin. They picked an all-male group of tribal employees and one elected official to serve on this board. I was called to their first organizational meeting and informed of their existence. I didn’t like it, but I was cordial. I asked the council politely, “What is the role of this board? Will you be looking over and deciding what news goes to print?”

“Yes,” the chairman of the Wotanin’s new board of directors responded.

I took a photograph of the board members and published the picture on the next issue’s front page. Along with the photo, I published a short article explaining that the tribal council had named a board, the purpose of which was to begin censoring the news.

The reaction from our readership was swift. They did not favor any censorship of the news, and they let their elected officials know. Other news outlets that subscribed to or exchanged news with us—such as a television station in Williston, North Dakota, some 70 miles to the east of the Fort Peck Reservation and one of the first national Indian newspapers, the Wassaja—also reacted to this article with more coverage of what was happening.

Public pressure stopped the censorship, but not the council’s attempt to stop our tribal newspaper’s coverage of our elected government. The next thing they did was advertise the position of editor. I’d been named “acting” editor in the summer of 1976 and was still working in that capacity in 1977. One day I was stopped on the street and asked whether I was resigning, since the position was being advertised in the Poplar Shopper, a non-Indian weekly newspaper that only covered the happenings in that community. For some reason, the board of directors did not advertise it in the reservationwide Wotanin Wowapi. I applied for the position and was eventually selected and voted in by a majority of the council.

There was tension in the tribal council chambers when John Morales was removed as Fort Peck tribal chairman. June 2004. Photo by Louis Montclair.

The Paper’s Commitment

From that time forward, I became accepted by the council, the tribal employees and those who staffed their programs, and the community in general. I continued to attend most of the committee meetings and all of the tribal council meetings. In the newspaper I created a format in which to report all statements and actions made by our elected officials, our programs and employees, including federal employees who worked for agencies that were there to serve our people, such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service.

I did not back away from controversy. Soon employees—who had insight into situations that were not right and needed to be brought to light in the newspaper—brought issues to my attention. These were situations not readily visible to people who didn’t keep the books or were not aware of what happened in some of the meetings, such as those held by various boards of directors. One tribal chairman had himself appointed to a board of directors of a tribal industry without following policy. He eventually took himself off that board and let the process move ahead in the proper way, but this only happened after I disclosed the irregularities in a front page story placed above the fold.

I approached my job strictly from the perspective of a journalist, without animus toward those on whom I reported. To my surprise, so did the council chairman who never seemed to hold a personal grudge against me and was always forthright in any interviews I did with him during the more than two decades he served on the council after serving one term as a chairman.

During the 1970’s and 80’s, there was strong support in the community for freedom of the press as I faithfully and happily covered our tribal government and its programs. Often I stayed up late into the night, typing with great detail each bit of news about the actions of our tribal council. Sometimes my minutes of the meetings took up two to four full newspaper pages, which is what people wanted and expected.

The process seemed to be smooth and, as time went by, people began to share with me all kinds of information that was being provided to our elected officials. At each full meeting of our government, the chairman’s office would provide each of the 12 council members a packet of correspondence received by his office, including memos and opinions from our tribes’ attorneys, travel requests, committee minutes, and any correspondence related to committee business, even copies of who was approved for enrollment in our Fort Peck Tribes. At each council meeting a packet was set aside for me, with my name on it, and I wrote stories about most of what I learned from reading its contents. If the matter was of interest to our tribal membership, I would use the letters or documents provided to me and make calls to add information to these stories.

One longtime tribal official, who served 50 years on the council and died while in office, understood and was supportive of freedom of the press. He served on the council and was also tribal chairman and was a strong leader who was well known on the local, state and national levels of government. He was the person who told the council that it should be OK for me to sit in on closed-door discussions between them and the tribes’ attorneys on a variety of important issues such as water rights, gaming, taxation and even personal issues such as the holding of incapacitated persons for treatment. He explained that in doing so I’d gain a good background when it came time to report on these issues. And it became quite a learning experience, one in which I gained a lot of knowledge about an issue’s historical perspective. Soon I was invited to travel with the council on some of their more important delegations so that I could see first hand what they were doing and report on it, which I did.

One October a young, rambunctious, popular man was elected to serve on the council. Eventually he came to frown on the Wotanin’s reports of some of the council’s actions, particularly when the stories involved him. Council members who also wanted to return to how things used to be quickly joined his side in what was becoming an uncomfortable confrontation. I was not willing to stop my reporting, so this councilman began writing his side of the story, while also trying to cut down the Wotanin. We published his words in the opinion section and let him have his say. He was eventually able to get some of the tribes’ funding of the newspaper cut, and he became someone who stood in opposition to freedom of the press on the reservation.

Several years later, when he was no longer on the council, he attended a Native American Journalists Association conference and saw and heard the efforts of the Wotanin lauded by other tribal press. Later, when he came back to the Fort Peck Reservation and ran again for tribal office, he came to the newspaper and apologized for his earlier actions. By then, however, inroads he’d made against the paper were being rejoined. In 2000, the tribal chairman was convinced by others to stop providing copies of committee minutes to the newspaper until the day of the full council meeting. (The only way we could find out what the committees were doing was to sit in on the meetings, but we were not able to sit in on every one of them. If we did, there would not be any other type of news in the paper.) Because of this change, we lost our edge in getting word out to the people what the council would be considering at their next meeting. Information, in general, provided to the press dwindled after that. By 2001, the press packet included only copies of committee minutes and the travel log.

The councils that were elected in 2001, 2003 and 2005 have used in many instances the “executive session” rule in Robert’s Rules of Order in conducting their meetings. In an effort to keep some issues out of the public eye, the majority of the elected officials have voted for closed sessions, thus keeping the press out. This means that the people do not learn what has gone into the decisions their tribal leaders are making.

In February 2005, what I saw as the final blow to the press occurred when the tribes’ “random” drug-testing policy was leveled on the four-member staff of the paper, all at the same time. I refused to abide by it because this testing was anything but random. As a result, I was fired from my job as editor. I didn’t take this matter to the people, as I had in the past. Nor did I file a grievance, which I had a right to do. I walked away in an act of defiance.

My termination did not mean the end of the paper. At the Wotanin, I had four freelance reporters who had their own beats to cover. One of them stepped forward and is acting editor. But my departure ended a lot of tribal council coverage, since that was my beat.

The Wotanin was my baby. I raised it, along with my four children. I took it from a tabloid-sized biweekly newspaper to a weekly full-sized paper that was bursting with news of our people. Each year our dependence on tribal monies to operate grew less and less, while the advertising and revenue from newspaper sales grew. Today, wherever I go, I come across people who tell me they miss me at the paper. I miss it, too.

Bonnie Red Elk, a Lakota-Dakota, served the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes as reporter/editor for nearly 30 years. The Native American Press Association presented her with two awards for Best Coverage of Tribal Government. She now freelances for the local non-Indian weekly newspaper on the Fort Peck Reservation.