Two things have dominated much of my professional and personal life during the 37 years since I graduated from journalism school in the United States: following American college sports and following Middle East politics, society and culture. Reading the U.S. mainstream press, especially in the early spring, I often have a hard time distinguishing between American media coverage of March Madness and Middle East Madness—both defined by intense emotions and extreme confrontation.

Through my professional lifetime of experience working for and with quality American and European journalists, and following their work daily, what I regret most is their tendency to report on the Middle East almost exclusively as an arena of aberration and violence. This is only exacerbated (and at times mystified) by the shattering combination of ignorance and fear of alien cultures and faiths.

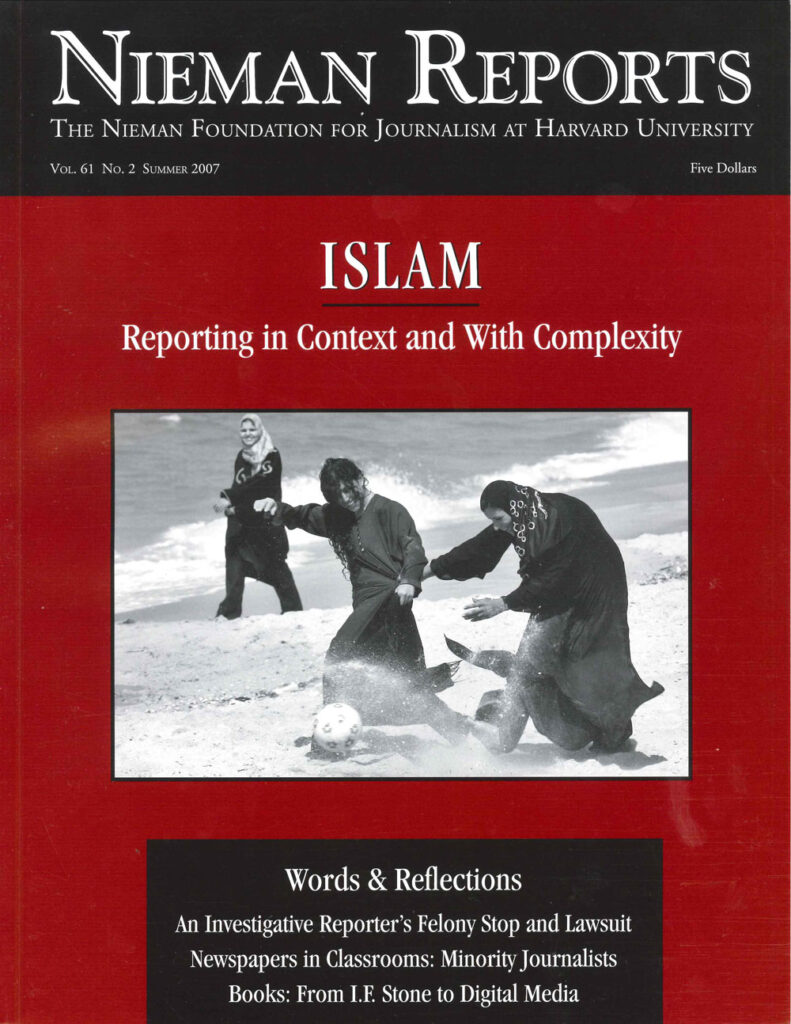

It is unfair and inaccurate to generalize too much, of course, but my critique of how this story has been mishandled stands the test of time. For the past half century, reporting about this region has been told primarily through the lens of conflict, extremism and violence; at the same time, the realities of hundreds of millions of ordinary Arabs, Iranians, Israelis, Turks and other small populations, whose daily lives are not defined by warfare or dominated by conflict, have been largely ignored. The prevalent news and imagery convey—and are defined by—emotionalism, exaggerated religiosity, and deep ethnic or religious prejudice, while the underlying human rhythms, prevailing moral norms, and routine cultural and political values of the 300 million or so Arabs are not presented accurately, fully or at all. Between the intemperance and drama of Dubayy, Gaza, Fallujah and Hizbullah, the U.S. news media have very little appetite for stories about Arabs who don't carry knives, shoot machine guns, launch grenades, or talk on gold-plated cell phones.

It is not surprising, therefore, that what I see from office, home and car windows throughout the Middle East does not match the images I see on U.S. newscasts. The juxtaposition is extreme and deeply frustrating. Reporting by the written press is only slightly better. This circumstance is brought about, in part, by the nature of the news media. I know because for 40 years I, too, have written "newsworthy" leads and headlines. Tension trumps routine yet, for those, like me, who have worked to foster better communication, journalistic coverage, and understanding between Arabs and Americans, this creates two problems:

Journalists in the West are missing the most important story in the Arab world: the quest by millions of ordinary people to create a better political and socioeconomic order, anchored in decent values, open to the world, pluralistic and tolerant yet asserting indigenous Arab-Islamic values. The wholesale attempt to transform autocracies into democracies and corrupt and often incompetent police states into more satisfying and accountable polities is a saga of epic and often heroic proportions. Most of the U.S. news media refuse to acknowledge or cannot even see this because of a relentless focus on Islamist violence, Israel, Hizbullah, Iran, Syria, terrorism, oil and the American army in Iraq.

A high price is paid for covering the Arab world primarily in terms of its public and political deviance, rather than its human ordinariness and the rhythms of its many different neighborhoods. This price is denominated in three interlocking and dangerous currencies that create a cycle of disdain and death that serves to define us today: (a.) a one-dimensional and largely negative and usually fear-filled image of the Arab world set in the mind of ordinary Americans; (b.) emotional and political support for the U.S. government in pursuit of its Middle East policies, with disastrous consequences for all concerned; (c.) the counterreaction from much of the Arab world, where a large majority of ordinary people and ruling elites are contemptuous of American policy; a very small band of criminal fanatics in al-Qaeda and associated groups goes a step further and wages war against Americans at home or abroad.

Such coverage of the Middle East—and Arab countries in it—is an integral element in perpetuating and exacerbating existing tensions and fear. (Arab coverage of Americans shares a lot of these same weaknesses.) All of this is made worse by the inherent bias—reflecting long-standing U.S. government policy and Israeli perspectives—embedded in most of this coverage. And when what is reported also stresses the Arab's anti-Israel and anti-U.S. sentiments of Arabs—and these are real—little space remains for reporting on the defining reality of ordinary Arab lives. This reality is the heroic durability and epic stoicism as ordinary Arabs demand to be treated in their countries as citizens with rights instead of as subjects, victims and chattel of modern Arab authoritarianism.

This narrative is all too familiar to American reporters; they've told this story often and with eloquence and persistence when, for example, Russians and Poles fought against Communism, and Chinese students and black South Africans waged struggles against their oppressive systems, and girls and women in Afghanistan battled for their rights at great risk. But this story is rarely told in Arab lands, where instead death and hatreds take center stage in stories filed by Western reporters—stories routinely insinuating the inscrutability of exotic and alien values and an inherently violent faith.

A half-century ago many in the American media ignored entirely or provided a distorted, incomplete and one-dimensional coverage of African Americans, then called Negroes. Reporters then, as now, accurately reflected prevalent values in much of American society. Journalists did not create this racism or oppression; they only reflected it in what they covered—and what they didn't report on—and, in doing so, aided in perpetuating its flaws and crime. Something similar is happening in reporting on the Arab world today, as prevailing political interests and norms, with a nod to crass commercialism, defeat what might otherwise be journalists' better instincts.

This is a difficult—and even profound—professional challenge. How do journalists make the lives and aspirations of Arab men and women who will not succumb to criminality or terror relevant to Western audiences? How do they do this when there is no iconic image of a solitary man standing before a tank, as happened in Tiananmen Square? The spirit of Arab defiance and self-assertion in the face of police states and foreign occupiers is the stuff of drama. It is also the force behind mass politics in the Arab world—a force that is increasingly being exploited and misused by extremist leaders far afield, such as Iran's president. Osama bin Laden and his gang of criminals has also tried desperately and repeatedly to tap into this mountain of discontent, in most cases without success.

Masses of ordinary, discontented Arabs have refused to turn violent to express their angst as they also refuse foreign hegemony or occupation as an antidote to their domestic abuse of power. They cling to religion and traditional social values, while demanding more accountable and participatory governance. They adhere to their powerful religious dictates of charity and tolerance and, in most parts of the Arab world, they insist on living in pluralistic societies. And despite the West's perception, almost desperately they seek to engage meaningfully with Americans, Europeans and others abroad who would reciprocate the quest for mutually beneficial relations.

With policies and rhetoric seemingly locked in place, along with gun sights, it is perhaps too much to expect Western political leaders to see this human reality beneath the surface of the political brutality of a regime such as Hosni Mubarak's in Egypt. Or to understand the mass anger tapped by Moktada al-Sadr in Iraq. I do, however, expect my journalist colleagues in the Western press to focus on this extraordinary human dynamic that defines this entire region.

It's a great story. It's also the most likely route to our mutual salvation and exit from the cycle of warfare and extremism that our incompetent leaders have fostered and that degrades us all.

Rami G. Khouri, a 2002 Nieman Fellow, is a Palestinian-Jordanian-American national. He is a Beirut-based internationally syndicated columnist (www.ramikhouri.com), director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, and editor at large of The Daily Star newspaper.