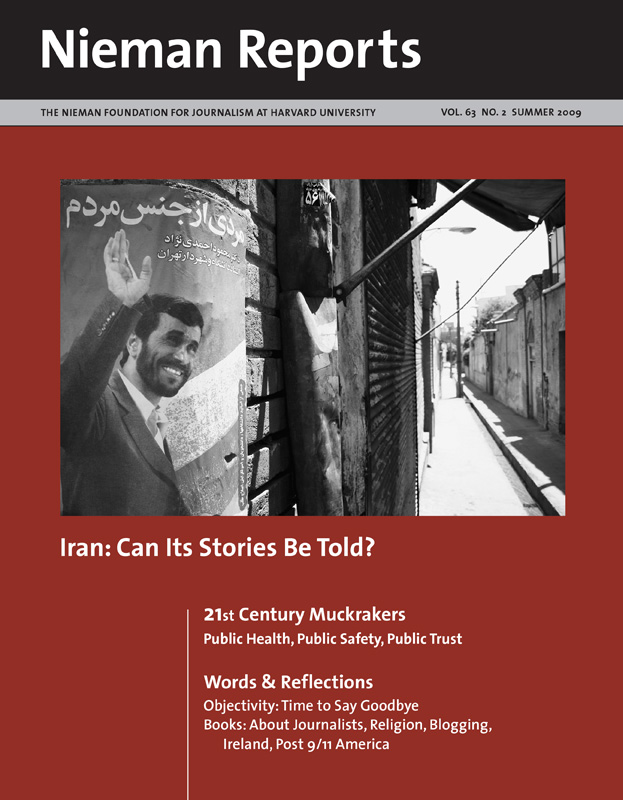

Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?

Journalists — Iranians and Westerners — share their firsthand experiences as they write about the challenges they confront in gathering and distributing news and information about Iran and its people. Their words and images offer a rare blend of insights about journalists’ lives and work in Iran. In the fifth part of our 21st Century Muckrakers series about investigative and watchdog reporting, the focus turns to coverage of issues involving public health, safety and trust. And in Words & Reflections, essays touch on objectivity, religion, blogging, Ireland and post 9/11 America.

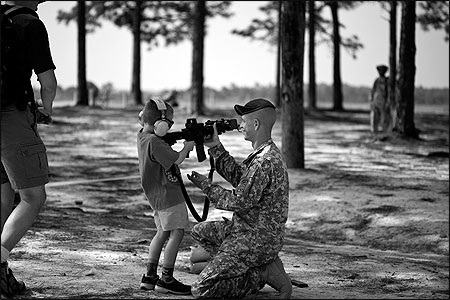

“All America Day” at Fort Bragg, home of the 82nd Airborne, is a time when the public can enter the base and take part in military games. Here, a soldier helps a boy fire a rifle equipped with a laser at human targets who drop to the ground and play dead when hit, part of the day’s festivities. Fort Bragg, North Carolina. 2006. Photo and text by Nina Berman.

The influence of war and militarism on American life, at a time when so many of our human and material resources are dedicated to military pursuits, lies at the heart of my present-day journey as a photographer. How do we, as a culture, visualize war? How do we fantasize about it? What role does the burgeoning homeland security apparatus—evermore present in our lives—play in the creation and dissemination of these fantasies?

I’ve collected my images in “Homeland,” a book published last year. The book shows scenes from daily life: bombers entertain sunbathers on summer weekends, suburban families clutch antinuke pills, small-town police train to hunt terrorists, and children dress up as would-be killers at spectacles of military recruitment.

Across the country, at simulation drills costing millions and involving thousands of participants, terrorist scenarios are imagined and played out. There are Islamic terrorists with nuclear bombs or hijacking planes, biological and chemical terrorists, school bus and shopping mall terrorists. There is even a defense contractor who specializes in casting the terrorists’ make-believe victims. Some of these events have the look and feel of state-sponsored performance art in which participants experience a powerful sense of identity and community through a militarized experience.

In trying to decode these scenes, I asked myself how much of this security represents a rational response to a legitimate threat. Or, I wondered, is it a well-funded show designed to keep Americans fixated on fear?

As I photographed small-town efforts to deter terror, I asked police and volunteer patrollers how they judge whether what they are doing is effective. “Because nothing has happened,” they’d respond. The logic of this answer revealed to me not so much the efficacy of their enterprise, but an inflated sense of their capacity to influence events. Challenge this assumption, as I sometimes did, and I’d be met with a response such as “Don’t you want security?” To answer “no” was to be labeled as a traitor; to say “yes,” led down the inevitable path of no armament being too expensive, no training without merit, no procedures too invasive.

When soldiers are about to be deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, sensitivity training is designed to simulate potential real-life experiences. At Fort Polk in Louisiana, scenarios are played out in a 100,000-acre area known as “the Box.” Last year, when I visited there, I was introduced to goats, not one but dozens, all of them tagged as government-issued extras in a war on terror script. They were there to provide the appearance of truth to a staged encounter between soldiers and a make-believe Iraqi farmer. At Fort Polk, the goats keep reproducing, and the geese, too, so they must be fed and fenced and taken care of by military farm hands. When one of the animals dies, I was told, the paperwork is a nightmare.

In southern Indiana I watched nuclear war played out on grassy hills and rubble piles at a facility that once housed the mentally disabled. Hundreds of civilians were paid nearly twice the local hourly wage to play victims of an Islamic terrorist attack in a Northern Command game that lasted eight days. Hundreds of first responders, joined by Army and Air Force soldiers and Marines, squeezed into a space designed to mimic downtown Indianapolis after a nuclear detonation. I witnessed total confusion, with rescue teams arriving late and getting lost, but the victims were happy—after all, this meant they were collecting overtime. Teams of National Guard photographers and videographers documented everything. They were making a movie to show members of Congress how well the exercise went so its organizers could apply for money for more training, and so it goes.

Every Memorial Day weekend, the Navy comes to New York City for rest and relaxation. News stories feature sailors having fun in Times Square. But other Fleet Week activities play out in the city through a series of five landing missions, such as the one I attended at Orchard Beach in the Bronx. Attack helicopters circled. Marines painted children’s faces in camouflage colors. New recruits pumped their fists and screamed, “This is what Iraq will be like!.” When the helicopters landed, a tarp was unfurled on the ground. It was filled with real weapons. The locals—children and adults—dove in, grabbed guns, and pointed them at each other. They took pictures with their cell phones as they lived it up under the gaze of Marine recruiters. The landing missions that year were considered so successful that the next year they were increased from five to nine, and one of them moved north to suburban Westchester County.

Photos and text by Nina Berman.

The White House communications officers take cover under a makeshift camouflage tent, set up during a visit by President George W. Bush to Shanksville, Pennsylvania, site of the 9/11 hijacked plane crash. 2002.

A woman caked with fake blood and tagged “priority one” earns $15 an hour playing a casualty of a nuclear weapon attack by Islamic terrorists at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center, a newly opened military facility that formerly housed the mentally disabled. Butlerville, Indiana. 2007.

Local residents are hired at $12.87 an hour to dress up as Iraqis and act out various scenarios designed to help soldiers train for deployment. In this photo, a car accident has occurred. Fort Polk, Louisiana. 2008.

Marines land attack helicopters, paint children in camouflage, and unfurl infantry weapons, including pistols with silencers, for the public’s amusement, with the unspoken aim of recruiting new Marines. Orchard Beach, Bronx, New York. 2007.

“Islamic terrorists” attack Midway Airport during a Homeland Security drill in Chicago, Illinois. The drill lasted several days and cost $16 million. 2003.

Nina Berman is the author and photographer of “Purple Hearts: Back from Iraq” and “Homeland,” published by Trolley Books. She is based in New York City. Her work can be viewed at www.ninaberman.com.