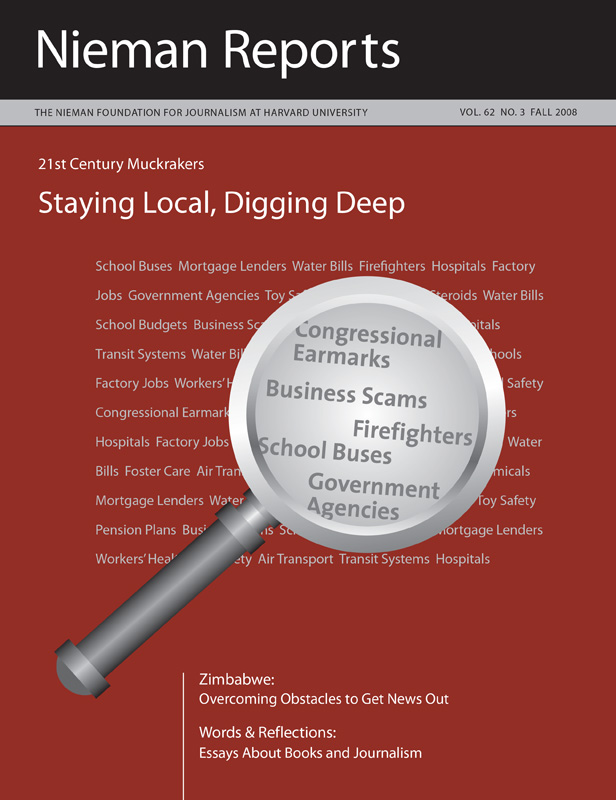

21st Century Muckrakers: Staying Local, Digging Deep

On this point, editors, reporters and newspaper readers agree. In a time of cutbacks and a shrinking news hole, at a moment when print is in peril and digital is dominant, watchdog and investigative reporting must remain at the core of journalism’s mission. In this third part of our 21st Century Muckrakers project, editors and reporters speak to how metro and regional newspapers are confronting the enormous challenges of today and offer clues to where this kind of reporting will likely be headed tomorrow.

In retrospect, I would like to be able to describe the Star-Telegram’s investigative team as a well-oiled engine that relentlessly pushes forward. But our team’s dynamics just didn’t work that way during the four months this year when we joined forces on a project. Stress, the mesh of personalities, and the heat of the moment—with deadline pressures intensified by newsroom cutbacks and our topic’s own timeline—created a different kind of combustion.

There were arguments, days of strained (if any) communication among us, and at least one smartly slammed door. There was also exultation, and a few eureka moments, and the time one of us dubbed “geeky pants day,” to commemorate when something went our way.

We set out with a simple plan to analyze a complex public hospital system. JPS Health Network operates three dozen clinics and two hospitals in and around Fort Worth, Texas; the network employs 4,000 nurses, doctors, technicians and janitors, and treats 156,000 patients each year. Reporter Anthony Spangler’s job was to dig out how much money the public hospital had in the bank. Yamil Berard was to probe the sources of its wealth. I was to hunt for people denied access to the system.

We expected our plan to change, and we weren’t disappointed. It twisted and morphed, at times on a daily basis. Remaining flexible—“shift and fire,” they call it in the military—became our strength. In the end, what emerged was a solid six-part newspaper series, and consequences followed for some whose actions and policies we’d investigated along the way. The hospital’s chief executive officer was shown the door. The chief financial officer also resigned. State inspectors and a health care accrediting agency launched surprise inspections, turning up dozens of violations. The cleaning service was fired. The board of directors began studying the impact copayments have on medical care for the poor. Board members left. And angry county commissioners and community groups lashed out.

Making Plans, Hitting Walls

In our newsroom, there had been talk for years about investigating the “hospital district,” which is the primary provider of health care for the poor. In 2005, the Star-Telegram had uncovered serious problems in jail inmates’ health care provided by JPS. Yet a year later, efforts to launch an investigation of the hospital district had fizzled due to the complexity that the reporting of this story required combined with the lack of newsroom resources. Still, a steady trickle of complaints and tips kept coming our way as the local medical society blasted JPS for failing its mission, and a survey of doctors showed concerns over hygiene and staffing as comments such as “we don’t help the poor” surfaced.

So in late 2007, Lois Norder, who oversaw investigative projects, drafted a team of two investigative reporters—Berard and myself—along with Spangler, who had covered the district as part of his county government beat. She’d already spent months sending out public information requests to state and federal government to gather financial details, which she’d carefully analyzed and put in spreadsheets. Our first assignment: to enter reading hell as we tackled scholarly articles and journals and slogged through government reports mostly without a working coffeemaker. We sifted through JPS’s annual audits cover to cover; most challenging was deciphering the mysteries of hospital finance.

Then, our real frustration began. Despite being a public institution subject to state public records law, the hospital district stonewalled some of our requests, though officials there said they were unaware of others. More than once I sent long e-mails detailing unanswered requests and then days or weeks later district officials would ask me what requests hadn’t been fulfilled. When information did reach us, it was sometimes unusable. At times JPS used the nuance in the wording of a request to skew their answers. None of this was surprising. JPS board members and county commissioners had long grumbled that the hospital district administrators were not forthcoming.

For our project, however, such delays were damaging. We could feel time rushing by and yet we were missing crucial chunks of essential financial information. We were told, for example, that the district didn’t know how many nurses it employed prior to 2006. We also suspected that enrollment in the hospital’s charity care program was flat even though the need for such medical services had increased with the growth in the county’s population. But we couldn’t get answers even as the statutory deadline to provide us the information passed.

Two months into our investigation, we were staring at a largely financial story, which was not what we’d envisioned, nor a story our readers would want to digest. At the district’s clinics, people I interviewed seemed resigned to long waits and were muted in their complaints about their care. For them, this was the only medical option they had. But we also had some success, mostly thanks to Spangler’s county sources, in getting a highly respected surgeon to go on the record with his critical observations about practices at the hospital, words he was willing later to repeat on video for our online presentation.

Berard, in the meantime, wrapped up an eye-opening analysis of hospital pricing and then set up a meeting with local religious leaders who had done their own review of the hospital’s finances. Though they were largely advocating for allowing illegal immigrants to access the hospital district’s health care, they also knew of patients who were angry about their treatment by JPS.

A Buried Report Is Found

One of my most challenging writing assignments during the project may have been the hour I spent carefully crafting an e-mail suggesting a meeting between the three reporters on the project to “talk about what we’ve got, what we need, and where we’re going with it.” In the end, we managed only a two-thirds majority and, as the project wore on, we began to grow impatient with one another. We were occasionally tripping over one another’s sources. Our meetings weren’t always going smoothly. But as we began to share potential sources, that helped lead to some breakthroughs. Berard, for instance, sacrificed a couple of her solid patient sources to us. She also initiated contact with another source whose information proved enormously valuable.

Spangler followed up and learned more that led to the discovery that JPS had commissioned a consultant’s study but kept its findings under wraps. Asking for the report from the public hospital would likely mean another long, drawn-out fight. The hospital district had contested releasing to us similar information about an American College of Surgeons report. (The college verifies trauma centers.)

Spangler arranged to get the series of consultant’s reports from another source. Late on a Thursday, he told us breathlessly about 600 pages depicting a hospital system replete with filth, ineptitude and callousness. That was what he called our “geeky pants day,” a phrase he says refers to a time “when one is so enthralled by something of a wonky nature that one begins to dance, metaphorically of course, in one’s ‘geeky pants.’”

And so we did, in a manner of speaking, as our editor, Tony, and I spent the weekend studying the reports. In them, we discovered information and data that corroborated the almost unbelievable stories that patients and doctors had been telling us, as word spread about our project. Unlike those whom we’d tried to interview at the clinics, these individuals sought us out with information about what they’d experienced and observed. Some told of flies buzzing around beds, bloodstained mattresses, and hostile treatment.

What we now had was an exhaustive inside look at critical areas of the hospital and its clinics. Just as the community groups had suspected and patients had conveyed, serious deficiencies were widespread. Large numbers of medical records were missing. Unnecessary tests were being performed. Nurses readying operating rooms that they’d thought were clean found blood, bone and fat globules on tables and on the floor.

Given what we’d learned, I went back and interviewed several patients three or four more times. One woman complained she’d been locked in a room at a hospital clinic, separated from her service dog. An asthma patient told me he was left off the food distribution list after being admitted to the hospital. A weeping mother told me how her son had gone to the hospital with chest pains and been sent home. He died hours later at another hospital. One surgeon told us that his patients were turned away because they could not afford the $20 copay, and he suspected some had died as a result. Another said that money, not quality of care, was driving the district’s decisions.

At about this same time, I sent another e-mail to the hospital district spelling out all of the information they’d said they couldn’t provide. I copied it to the board chairman. Suddenly about a dozen spreadsheets were sent our way. As we suspected, one showed the district had fewer people enrolled in its charity care program than five years earlier. Despite this, we knew from looking at the financial records that year after year the hospital district had deposited tens of millions of dollars into its bank accounts—money that was supposed to go toward providing medical care for the poor.

With notebooks of three reporters now bulging and spreadsheets proliferating, Norder created order out of our informational chaos. Using huge sticky notes, she broke down by category the hospital district’s systemic flaws. Her notes became my cue cards, which as the project’s lead writer I used to synthesize the work we’d done as individual reporters and as a team. Discussing this later with Norder, we agreed that completing this project was akin to falling in love. At first, there was the desire to maintain control, even as it seemed everything was spinning out of control. Then came the realization of liking being in this new place, even though getting here required relinquishing control.

RELATED WEB LINK

JPS: Prescription for Profit

—www.star-telegram

.com/jps/With our project available in multimedia on our Web site, our investigative reporting on related topics goes on, though in different ways. No longer are the three of us intertwined by one specific project; instead, each of us is building on the expertise gained on this assignment and using it in more frequent enterprise reporting. Stories I’ve done recently about Texas laws that keep from the public information about the quality of hospital and physician care are a natural outgrowth of this project, as is the ongoing work of the others on this team.

Public reaction was overwhelming to our series, but the comments I heard from the higher-ups at the paper were also gratifying. Coming off a round of layoffs, with morale low, the project served as a reminder in these troubling times of what a newspaper can accomplish for the community it serves.

Darren Barbee is a staff writer at the Fort Worth (Tex.) Star-Telegram.

There were arguments, days of strained (if any) communication among us, and at least one smartly slammed door. There was also exultation, and a few eureka moments, and the time one of us dubbed “geeky pants day,” to commemorate when something went our way.

We set out with a simple plan to analyze a complex public hospital system. JPS Health Network operates three dozen clinics and two hospitals in and around Fort Worth, Texas; the network employs 4,000 nurses, doctors, technicians and janitors, and treats 156,000 patients each year. Reporter Anthony Spangler’s job was to dig out how much money the public hospital had in the bank. Yamil Berard was to probe the sources of its wealth. I was to hunt for people denied access to the system.

We expected our plan to change, and we weren’t disappointed. It twisted and morphed, at times on a daily basis. Remaining flexible—“shift and fire,” they call it in the military—became our strength. In the end, what emerged was a solid six-part newspaper series, and consequences followed for some whose actions and policies we’d investigated along the way. The hospital’s chief executive officer was shown the door. The chief financial officer also resigned. State inspectors and a health care accrediting agency launched surprise inspections, turning up dozens of violations. The cleaning service was fired. The board of directors began studying the impact copayments have on medical care for the poor. Board members left. And angry county commissioners and community groups lashed out.

Making Plans, Hitting Walls

In our newsroom, there had been talk for years about investigating the “hospital district,” which is the primary provider of health care for the poor. In 2005, the Star-Telegram had uncovered serious problems in jail inmates’ health care provided by JPS. Yet a year later, efforts to launch an investigation of the hospital district had fizzled due to the complexity that the reporting of this story required combined with the lack of newsroom resources. Still, a steady trickle of complaints and tips kept coming our way as the local medical society blasted JPS for failing its mission, and a survey of doctors showed concerns over hygiene and staffing as comments such as “we don’t help the poor” surfaced.

So in late 2007, Lois Norder, who oversaw investigative projects, drafted a team of two investigative reporters—Berard and myself—along with Spangler, who had covered the district as part of his county government beat. She’d already spent months sending out public information requests to state and federal government to gather financial details, which she’d carefully analyzed and put in spreadsheets. Our first assignment: to enter reading hell as we tackled scholarly articles and journals and slogged through government reports mostly without a working coffeemaker. We sifted through JPS’s annual audits cover to cover; most challenging was deciphering the mysteries of hospital finance.

Then, our real frustration began. Despite being a public institution subject to state public records law, the hospital district stonewalled some of our requests, though officials there said they were unaware of others. More than once I sent long e-mails detailing unanswered requests and then days or weeks later district officials would ask me what requests hadn’t been fulfilled. When information did reach us, it was sometimes unusable. At times JPS used the nuance in the wording of a request to skew their answers. None of this was surprising. JPS board members and county commissioners had long grumbled that the hospital district administrators were not forthcoming.

For our project, however, such delays were damaging. We could feel time rushing by and yet we were missing crucial chunks of essential financial information. We were told, for example, that the district didn’t know how many nurses it employed prior to 2006. We also suspected that enrollment in the hospital’s charity care program was flat even though the need for such medical services had increased with the growth in the county’s population. But we couldn’t get answers even as the statutory deadline to provide us the information passed.

Two months into our investigation, we were staring at a largely financial story, which was not what we’d envisioned, nor a story our readers would want to digest. At the district’s clinics, people I interviewed seemed resigned to long waits and were muted in their complaints about their care. For them, this was the only medical option they had. But we also had some success, mostly thanks to Spangler’s county sources, in getting a highly respected surgeon to go on the record with his critical observations about practices at the hospital, words he was willing later to repeat on video for our online presentation.

Berard, in the meantime, wrapped up an eye-opening analysis of hospital pricing and then set up a meeting with local religious leaders who had done their own review of the hospital’s finances. Though they were largely advocating for allowing illegal immigrants to access the hospital district’s health care, they also knew of patients who were angry about their treatment by JPS.

A Buried Report Is Found

One of my most challenging writing assignments during the project may have been the hour I spent carefully crafting an e-mail suggesting a meeting between the three reporters on the project to “talk about what we’ve got, what we need, and where we’re going with it.” In the end, we managed only a two-thirds majority and, as the project wore on, we began to grow impatient with one another. We were occasionally tripping over one another’s sources. Our meetings weren’t always going smoothly. But as we began to share potential sources, that helped lead to some breakthroughs. Berard, for instance, sacrificed a couple of her solid patient sources to us. She also initiated contact with another source whose information proved enormously valuable.

Spangler followed up and learned more that led to the discovery that JPS had commissioned a consultant’s study but kept its findings under wraps. Asking for the report from the public hospital would likely mean another long, drawn-out fight. The hospital district had contested releasing to us similar information about an American College of Surgeons report. (The college verifies trauma centers.)

Spangler arranged to get the series of consultant’s reports from another source. Late on a Thursday, he told us breathlessly about 600 pages depicting a hospital system replete with filth, ineptitude and callousness. That was what he called our “geeky pants day,” a phrase he says refers to a time “when one is so enthralled by something of a wonky nature that one begins to dance, metaphorically of course, in one’s ‘geeky pants.’”

And so we did, in a manner of speaking, as our editor, Tony, and I spent the weekend studying the reports. In them, we discovered information and data that corroborated the almost unbelievable stories that patients and doctors had been telling us, as word spread about our project. Unlike those whom we’d tried to interview at the clinics, these individuals sought us out with information about what they’d experienced and observed. Some told of flies buzzing around beds, bloodstained mattresses, and hostile treatment.

What we now had was an exhaustive inside look at critical areas of the hospital and its clinics. Just as the community groups had suspected and patients had conveyed, serious deficiencies were widespread. Large numbers of medical records were missing. Unnecessary tests were being performed. Nurses readying operating rooms that they’d thought were clean found blood, bone and fat globules on tables and on the floor.

Given what we’d learned, I went back and interviewed several patients three or four more times. One woman complained she’d been locked in a room at a hospital clinic, separated from her service dog. An asthma patient told me he was left off the food distribution list after being admitted to the hospital. A weeping mother told me how her son had gone to the hospital with chest pains and been sent home. He died hours later at another hospital. One surgeon told us that his patients were turned away because they could not afford the $20 copay, and he suspected some had died as a result. Another said that money, not quality of care, was driving the district’s decisions.

At about this same time, I sent another e-mail to the hospital district spelling out all of the information they’d said they couldn’t provide. I copied it to the board chairman. Suddenly about a dozen spreadsheets were sent our way. As we suspected, one showed the district had fewer people enrolled in its charity care program than five years earlier. Despite this, we knew from looking at the financial records that year after year the hospital district had deposited tens of millions of dollars into its bank accounts—money that was supposed to go toward providing medical care for the poor.

With notebooks of three reporters now bulging and spreadsheets proliferating, Norder created order out of our informational chaos. Using huge sticky notes, she broke down by category the hospital district’s systemic flaws. Her notes became my cue cards, which as the project’s lead writer I used to synthesize the work we’d done as individual reporters and as a team. Discussing this later with Norder, we agreed that completing this project was akin to falling in love. At first, there was the desire to maintain control, even as it seemed everything was spinning out of control. Then came the realization of liking being in this new place, even though getting here required relinquishing control.

RELATED WEB LINK

JPS: Prescription for Profit

—www.star-telegram

.com/jps/With our project available in multimedia on our Web site, our investigative reporting on related topics goes on, though in different ways. No longer are the three of us intertwined by one specific project; instead, each of us is building on the expertise gained on this assignment and using it in more frequent enterprise reporting. Stories I’ve done recently about Texas laws that keep from the public information about the quality of hospital and physician care are a natural outgrowth of this project, as is the ongoing work of the others on this team.

Public reaction was overwhelming to our series, but the comments I heard from the higher-ups at the paper were also gratifying. Coming off a round of layoffs, with morale low, the project served as a reminder in these troubling times of what a newspaper can accomplish for the community it serves.

Darren Barbee is a staff writer at the Fort Worth (Tex.) Star-Telegram.