Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

The cybernetic tablets inscribed back when the Internet was beginning to become a sensation—let’s say the mid-1990’s—promised many wonderful things, including a rebirth of journalistic independence, new media profit centers, more news depth, and more diversified news and discussion. There was also renewed hope for salvaging representative government by raising the level of citizen knowledge of—and participation in—public affairs, including electronic town meetings and voting on the Internet. We finally seemed to be approaching the point of disproving press critic A.J. Leibling’s most enduring message, that freedom of the press is limited to those who own one.

Suddenly, any common drudge could become a worldwide publisher with his or her own Web site. Costs were no longer a problem. Infinity was the limit. Nothing inspired such hopes more than the arrival of Salon and Slate, the pioneering Internet magazines. With only $50,000 in seed money from Apple in 1995 and larger sums later from Apple and Adobe, former Hearst journalist David Talbot created the well written, sometimes sordid Salon. Its Initial Public Offering (IPO) in June 1999 attracted some $26 million, topped by $15 million from private sources. Talbot counted on advertising to provide the necessary revenue. Microsoft had a different slant on financing. It launched Slate in 1996 on the assumption that, after an initial run of free editions, quality journalism could attract enough online subscriptions to make a profit without the need for advertising and its pressures to alter the true picture.

By the first year of the new millennium, however, such dreams were fading fast. Salon’s stock price, which once reached $15, was flickering around $1 in October, while its operating funds were steadily disappearing. A year after its successful IPO, it revamped its look (to the dismay of many fans), then revamped the revamping and laid off 13 employees. For the first time, writers were being kept or fired on the basis of viewer “hits” on specific articles. Reality also struck APBnews.com, a creative webzine hooked on crime and justice. [See story about APBnews.com on page 31.] It was forced to dismiss its entire staff of 140. Web publishers were learning some lessons that have long governed printed matter.

Buffeted by similar forces, the profit-conscious Tribune Company fired 34 employees from its Web site, including 20 at the Los Angeles Times. And with a (third?) finger to the ill winds, The New York Times and several other traditional news producers decided to hold back plans to solicit public funds for their Web operations. Microsoft’s window of opportunity also narrowed, forcing the firm to wipe Slate clean of any cost to viewers in favor of subsidized publication. Neither ads nor subscriptions seemed to work for enterprising online journalism.

The crash of dot-com stock prices last spring helped prick the bubble of Internet advertising. According to The Washington Post in October, only about five people out of 10,000 actually click through ad links to other news/info sights. People also click past news that costs money. Princeton Research Associates report that only 11 percent have ever paid for news on the Web.

Reality was also catching up to individual pioneers. Although Matt Drudge (President Clinton calls him “Sludge”) was up and running for many moons before he hit big time with his stolen Monica Lewinsky scoop in early 1998, he still shows no visible means of support, not to mention riches. In October, he claimed some 55 million hits, though Media Metrix, the “Nielsen Rating” of the Internet, put his “unique visitors” at a more modest 889,000, ranking him 18th on the news list. That meant approximately 54,111,000 were repeat visits. Yet this brash young opportunist operating out of a tiny apartment with an outdated computer was turning out to be far less creative than advertised. Despite his reputation for scandalizing the political left with documented and undocumented allegations—like an Internet version of Rush Limbaugh—Drudge has become almost completely dependent on mainline news services for his headlines since his tipsters from the Vast Right-Wing Conspiracy lost their political motivation.

Enterprising journalism is also rare at the sites of large news organizations. The predominant America Online, with all the output of Time magazine and CNN available to it, still relies on AP for news of the nation and world. Even big newspapers lean almost exclusively on AP and Reuters for their Web sites, largely because of the need for rapid updates. A spot check of such addresses in October showed that newspapers tend to offer little more news on their Web sites than what they print. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s ajc.com seems typical, with its use of AP for all national and world news stories online.

Newspapers also don’t seem to be rushing to link printed stories to their Web sites. The Chicago Tribune, widely admired for its melding of radio, TV and print news operations, daily tells readers that it “offers expanded coverage of the day’s news, with content produced specifically for the World Wide Web, audio and visual enhancements and other text of the portal newspaper.” But in the few observed editions, none of the stories in the main news section carried shirttails to Web sites. Ben Estes, editor of chicagotribune.com, said merely that the decision varies by story.

The Cox-owned Atlanta Journal-Constitution was a notable exception, regularly ending major stories with references to outside Web addresses, not its own, for more information. The Washington Post used to carry numerous story tag lines referring to its Web site but seems to have cut back. Requests for an explanation were not answered. The only item on the Tribune’s corporate Web site on October 24 was brief: “Tribune declares quarterly dividend; sets annual meeting date.” Newspapers don’t seem to be trying hard to add depth to their Web presence.

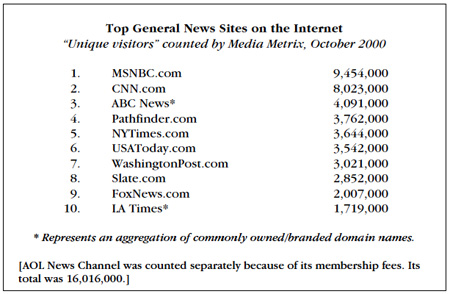

On network evening news shows, however, references to company Web sites are extensive. That might be why TV-owned sites lead the list of most popular ones. MSNBC.com and CNN.com continue in first and second place (with 9.5 million and 8.0 million “unique visitors” respectively), far ahead of others specializing in news, according to Media Metrix data for October. [See accompanying table above.] Surprise: Of the 20 most popular news/info addresses, the 12 offering full news menus were all parts of traditional news organizations. The one exception, Microsoft’s Slate, has a broad sweep but its coverage is not like the others. Three of the other seven focused on weather, two were info browsers, one was the Discovery channel, and one was a campaign site for George W. Bush.

An informal check of a week’s evening news programs in late October showed that CNN, NBC and CBS all exceeded ABC in references to their Internet sites. Naturally, TV Web sites contain far more volume than their regular news programs. Like publisher sites, they also offer lots of color, ads, promos, links and lists, resulting in a rather cluttered appearance. (This article does not address the broadband applications of audio and video, a further diversion enjoyed by only about three million out of some 35 million users of the Web.)

The flip side to this fractured, glitzy stuff, of course, is a motley parade of quirky, frenetic surfers with less and less interest in news details even when available. News sites are turning into little more than bulletin boards increasingly loaded with retail pitches. [See box above below.] The newest craze to customize news to fit viewer wishes further downgrades the potential broadening effect of the Internet. Web journalism seems to be catching a virulent form of tabloidism. It might not be long before Jay Leno and crew all have their own news sites, drawing news seekers away from serious sites with their own take on the headlines. They already are the news anchors of choice for countless dropouts from network news.

The Internet is also encouraging the steady downsizing of serious news that has infected mainstream media, especially during the last decade. The main catalyst has been Wall Street’s power to insist that publicly owned media firms toe the standards for all widget makers: higher profits every quarter. It’s basically this pressure that causes news executives to increasingly omit or cut serious news of the nation and the world and play up trivia and emotion to boost audience figures and ad volume. Under such pressure, it is virtually impossible for even the most conscientious editor to give full attention to what’s important for citizens to stop democracy from hemorrhaging.

Today’s journalism has acquired a drive-by quality, as it hits on a hot topic one day, then runs away from it the next, before anyone can digest the meaning. The TV version is parachute journalism. The Internet adds to the damage by creating drive-by news consumers who skip blithely from bulletin to bulletin while feeling they are keeping up with things. To be sure, the World Wide Web in total offers an ever-growing array of news and information. But its hot-button nature tends to emphasize the worst of journalism rather than the best. The effect can’t help but diminish citizen awareness of public affairs and interest in voting. Media managers have become so hung up on quick ratings and profits that—almost like mad lemmings—they revel in their own freedom while virtually ignoring their obligation to keep the electorate informed enough to maintain a fully representative system of government.

Not only do the mainstream media completely dominate news on the Web. They are continuing their corporate consolidation and homogenization online with shared ownerships, mutual links, even the same ads, photos, news stories, typography and layout. The trend toward massive sharing, including trading journalists, rather than competition has also been cyberized. Forget the promises about diversity. The news business is using the Web to create the most powerful cartel of all. And government regulators continue to doze.

Like many other rebels, the once-proud Salon has been sucked into the fold. Consider its plans for politics2000.com announced a year ago. Its press release boasted of special ties to CBS News, America Online, C-SPAN, United Feature Syndicate, and Isyndicate. It also noted an equity and content agreement with Rainbow Media Holdings, Inc., a subsidiary of Cablevision Systems Corporation and NBC, to produce a TV series. Among organizations agreeing to carry Salon “content” were AOL, a part-owner of Salon, as well as AltaVista, Reuters, CNN.com and CNET. Among “advertising sponsors” were IBM, Microsoft and Intel, plus 275 others.

Is this the new shape of cutting-edge journalism? With Salon on life supports, Slate on subsidies and Drudge living off the wires, it looks as if the future is already past.

—Arthur E. Rowse, with slight embellishments

Arthur E. Rowse is the author of “Drive-By Journalism: The Assault on Your Need to Know,” published this year by Common Courage Press in Monroe, Maine. Rowse, a veteran journalist and media critic, retired from U.S. News & World Report, after serving on the city desks of The Boston Globe, the Boston Herald/Traveler and The Washington Post.