When Theodore H. White wrote his landmark book, “The Making of the President 1960,” he helped invent a new style of political journalism. His insider, fly-on-the-wall style of reporting made for fascinating, insightful reading, and the rest of us have been imitating him ever since.

But now, it’s become too much of a good thing in the Iowa caucus campaigns. One reporter quietly hanging around the candidate and a campaign can provide useful reading at the end of the campaign. Hundreds crowding around that candi-date—now outfitted with a body microphone or two—and filing instantly and constantly into the 24hour news cycle changes the very nature of the story. Here, caucus campaign events are no longer quaint, intimate gatherings of neighbors who talk politics before passing a verdict on candidates. Often, they are mob scenes.

For better or worse, an early test of presidential candidate strength occurs in my backyard—Iowa—every four years. This year 124,331 Iowa Democrats trekked to 1,991 precinct caucuses to pass judgment on their party’s presidential candidates. This verdict was covered by about 1,200 media people—an average of one journalist for every 100 caucus-goers and about 240 per each of the five candidates who actively campaigned here. It’s a bit much. Too much. The crush of media attention, while welcomed by Iowa’s hotel and restaurant businesses, has changed the nature of presidential politics in these early caucuses.

This evolution from intimate to intimidating started after 1972, when a young Gary Hart engineered one of those “unexpectedly strong second-place showings” by George McGovern against Edmund Muskie in the Democratic caucuses here. That winter about a dozen journalists showed up to chronicle the campaign events. McGovern then went on to upset Muskie for the nomination that year, and in doing so he put Iowa’s precinct caucuses on the map as a test of strength. The verdict in Iowa now meant something.

Four years later, Jimmy Carter raised the Hart/McGovern strategy to an art form, with many more media people watching. When Carter went from obscurity in Iowa to the White House in Washington, we knew that in 1980 events here would get even more attention. They did, and each election cycle more and more reporters arrive to watch Iowans quiz the candidates and attend their caucuses.

It’s a not-so-virtuous circle. It feeds on itself. The selection of a President is a big story. So it’s natural journalists want to cover it, and new technologies make it easier for more people to do. New media outlets—like Web sites and 24-hour cable TV—create a never-ending demand for content. Other states, jealous of the media attention given the early states of Iowa and New Hampshire, have moved their caucuses and primaries closer to the two leadoff events and triggered the law of unintended consequences. Now the political community puts forward the expectation that candidates must do well in Iowa and New Hampshire in order to stay alive and go on to win in later contests; they have no time to recover if they don’t. Therefore, candidates increase their spending and campaigning time in Iowa, with a growing cadre of digitized journalists in hot pursuit.

What were once small meetings of party activists held in living rooms have morphed into large gatherings that candidates work hard to pack with their supporters. Only four percent of the caucuses this year were held in living rooms. No longer do candidates quietly move around the state as Carter did in 1975. Only in the very earliest days do you see that sort of campaigning here, but it’s not long until C-SPAN, the cable networks, and the Webcasters show up to beam these events to the rest of the world.

The smallest gaffe can become magnified. Suddenly, the off-Broadway performances that Iowa and New Hampshire used to afford candidates have become the main event themselves. Yet this isn’t all bad. After all, this is the start of a presidential campaign, and whenever and wherever the nation starts picking a President it’s going to be a big story. Move the start to some other state and the same media overkill will happen there.

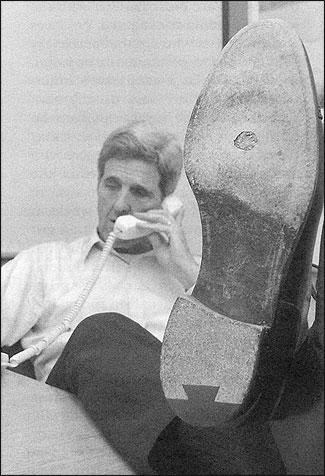

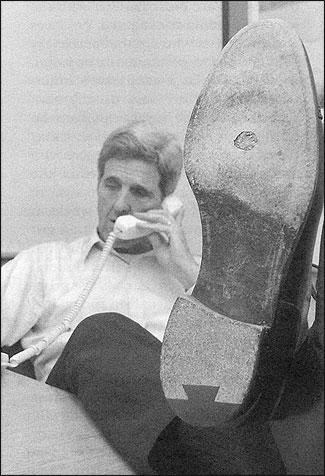

Senator John Kerry put his feet up and made phone calls during a day of campaigning in New Hampshire in November. Photo by Jim Korpi/Concord Monitor.

Improving Horserace Journalism

But I come not to damn horserace journalism but to praise it. I’m a great practitioner of horserace journalism. In a presidential campaign, the big story is always who is most likely to win. I’ve covered politics in Iowa for 30 years, and every four years all sorts of people come up to me with one question: “Who’s going to win?” That’s understandable. They want to know who their President is going to be. No one has ever come up to me and asked: “What’s Howard Dean’s infrastructure policy?”

What I’d like is for horserace journalism to be better than it is now, and that does not mean just packing more handicappers into the press box. Every four years the nation’s best political writers and reporters—well, most of them—trek out here, but they spend too much time on the candidates and not enough on the voters. (There are some who think they can cover Iowa by sitting in their offices in Washington and Manhattan just reading the polls, The Hotline, or ABC News’s The Note. Such reading is required, but so is some lab work.)

It’s time to break up the press pack. Let wire service reporters or pools of journalists do the “death watch” and the “gaffe watch” on candidates. (Let’s admit that’s why much of that pack is there, waiting for one of those two things to happen.) It’s time for more of us horserace journalists to get down into the paddocks, talk to the jockeys, the owners, and the breeders as well as the fans. By spending an evening with a bunch of vets at a Legion Hall in Osceola, Iowa, I learned much about Senator John Kerry’s growing appeal to veterans. They’d gathered to hear Kerry’s old friend, former Vietnam vet and senator from Georgia, Max Cleland. Veterans from a variety of wars—along with their spouses—complained about the direction of the country they’d fought for, the poor treatment they felt veterans are getting, and the need to do something about this. It became clear to me that something was going on here, and the candidate wasn’t even around.

During this campaign, nearly every political journalist wrote (and then wrote some more) about the explosion of Internet-based politics, thanks to Dean and his first campaign manager, Joe Trippi. Perhaps that story was overdone. Before the caucuses, about 60 percent of likely caucus-goers told the Iowa Poll they had gotten no information about the campaign from the Internet. While we are entranced with our BlackBerries, most voters aren’t. They still make their decisions the old-fashioned way—by reading, watching TV, and by talking things over with kin, friends and neighbors. In Iowa, what turned out to be the most effective weapon wasn’t the Internet organization that Dean used to raise money and recruit volunteers. It was the personal networks of veterans and local firefighters that Kerry built.

Did the political press make too much of the Internet effect on this campaign and not enough of the old-fashioned, personal work of campaigning? Perhaps. Had I spent more time in Legion halls and less time on the Internet, I would not have gone on “Fox News Sunday” the day before the caucuses and flippantly predicted a Dean win in Iowa. (Kerry won.) When it comes time for my job review, I will point to the prescient column I wrote in December—in part based on that Legion Hall experience—about Kerry’s rising fortunes in Iowa and just hope the boss wasn’t watching “Fox News Sunday.”

It turns out that Iowa’s caucus-goers had moved beyond anger at President Bush over the Iraq War to a desire to do something about it, like defeat him. As the Iraq War’s beginning diminished as a top voting issue, Kerry’s locally built organization and his sharper message turned out to be much more effective than the one Dean built over the Internet.

It’s back to the future next time. Shoe leather beats BlackBerries for getting to the bottom of the story. And next time seems to be happening earlier than we might like. The 2004 Democrats cleared out of here just two weeks ago, and now signs of the early stirring for 2008 can already be found: Rudy Giuliani was down the street last night speaking at the local chamber of commerce dinner. It was his second visit to Iowa this month.

David Yepsen is The Des Moines Register’s political columnist. He has covered Iowa politics for 30 years, and in the fall of 1989 he was a fellow at the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

But now, it’s become too much of a good thing in the Iowa caucus campaigns. One reporter quietly hanging around the candidate and a campaign can provide useful reading at the end of the campaign. Hundreds crowding around that candi-date—now outfitted with a body microphone or two—and filing instantly and constantly into the 24hour news cycle changes the very nature of the story. Here, caucus campaign events are no longer quaint, intimate gatherings of neighbors who talk politics before passing a verdict on candidates. Often, they are mob scenes.

For better or worse, an early test of presidential candidate strength occurs in my backyard—Iowa—every four years. This year 124,331 Iowa Democrats trekked to 1,991 precinct caucuses to pass judgment on their party’s presidential candidates. This verdict was covered by about 1,200 media people—an average of one journalist for every 100 caucus-goers and about 240 per each of the five candidates who actively campaigned here. It’s a bit much. Too much. The crush of media attention, while welcomed by Iowa’s hotel and restaurant businesses, has changed the nature of presidential politics in these early caucuses.

This evolution from intimate to intimidating started after 1972, when a young Gary Hart engineered one of those “unexpectedly strong second-place showings” by George McGovern against Edmund Muskie in the Democratic caucuses here. That winter about a dozen journalists showed up to chronicle the campaign events. McGovern then went on to upset Muskie for the nomination that year, and in doing so he put Iowa’s precinct caucuses on the map as a test of strength. The verdict in Iowa now meant something.

Four years later, Jimmy Carter raised the Hart/McGovern strategy to an art form, with many more media people watching. When Carter went from obscurity in Iowa to the White House in Washington, we knew that in 1980 events here would get even more attention. They did, and each election cycle more and more reporters arrive to watch Iowans quiz the candidates and attend their caucuses.

It’s a not-so-virtuous circle. It feeds on itself. The selection of a President is a big story. So it’s natural journalists want to cover it, and new technologies make it easier for more people to do. New media outlets—like Web sites and 24-hour cable TV—create a never-ending demand for content. Other states, jealous of the media attention given the early states of Iowa and New Hampshire, have moved their caucuses and primaries closer to the two leadoff events and triggered the law of unintended consequences. Now the political community puts forward the expectation that candidates must do well in Iowa and New Hampshire in order to stay alive and go on to win in later contests; they have no time to recover if they don’t. Therefore, candidates increase their spending and campaigning time in Iowa, with a growing cadre of digitized journalists in hot pursuit.

What were once small meetings of party activists held in living rooms have morphed into large gatherings that candidates work hard to pack with their supporters. Only four percent of the caucuses this year were held in living rooms. No longer do candidates quietly move around the state as Carter did in 1975. Only in the very earliest days do you see that sort of campaigning here, but it’s not long until C-SPAN, the cable networks, and the Webcasters show up to beam these events to the rest of the world.

The smallest gaffe can become magnified. Suddenly, the off-Broadway performances that Iowa and New Hampshire used to afford candidates have become the main event themselves. Yet this isn’t all bad. After all, this is the start of a presidential campaign, and whenever and wherever the nation starts picking a President it’s going to be a big story. Move the start to some other state and the same media overkill will happen there.

Senator John Kerry put his feet up and made phone calls during a day of campaigning in New Hampshire in November. Photo by Jim Korpi/Concord Monitor.

Improving Horserace Journalism

But I come not to damn horserace journalism but to praise it. I’m a great practitioner of horserace journalism. In a presidential campaign, the big story is always who is most likely to win. I’ve covered politics in Iowa for 30 years, and every four years all sorts of people come up to me with one question: “Who’s going to win?” That’s understandable. They want to know who their President is going to be. No one has ever come up to me and asked: “What’s Howard Dean’s infrastructure policy?”

What I’d like is for horserace journalism to be better than it is now, and that does not mean just packing more handicappers into the press box. Every four years the nation’s best political writers and reporters—well, most of them—trek out here, but they spend too much time on the candidates and not enough on the voters. (There are some who think they can cover Iowa by sitting in their offices in Washington and Manhattan just reading the polls, The Hotline, or ABC News’s The Note. Such reading is required, but so is some lab work.)

It’s time to break up the press pack. Let wire service reporters or pools of journalists do the “death watch” and the “gaffe watch” on candidates. (Let’s admit that’s why much of that pack is there, waiting for one of those two things to happen.) It’s time for more of us horserace journalists to get down into the paddocks, talk to the jockeys, the owners, and the breeders as well as the fans. By spending an evening with a bunch of vets at a Legion Hall in Osceola, Iowa, I learned much about Senator John Kerry’s growing appeal to veterans. They’d gathered to hear Kerry’s old friend, former Vietnam vet and senator from Georgia, Max Cleland. Veterans from a variety of wars—along with their spouses—complained about the direction of the country they’d fought for, the poor treatment they felt veterans are getting, and the need to do something about this. It became clear to me that something was going on here, and the candidate wasn’t even around.

During this campaign, nearly every political journalist wrote (and then wrote some more) about the explosion of Internet-based politics, thanks to Dean and his first campaign manager, Joe Trippi. Perhaps that story was overdone. Before the caucuses, about 60 percent of likely caucus-goers told the Iowa Poll they had gotten no information about the campaign from the Internet. While we are entranced with our BlackBerries, most voters aren’t. They still make their decisions the old-fashioned way—by reading, watching TV, and by talking things over with kin, friends and neighbors. In Iowa, what turned out to be the most effective weapon wasn’t the Internet organization that Dean used to raise money and recruit volunteers. It was the personal networks of veterans and local firefighters that Kerry built.

Did the political press make too much of the Internet effect on this campaign and not enough of the old-fashioned, personal work of campaigning? Perhaps. Had I spent more time in Legion halls and less time on the Internet, I would not have gone on “Fox News Sunday” the day before the caucuses and flippantly predicted a Dean win in Iowa. (Kerry won.) When it comes time for my job review, I will point to the prescient column I wrote in December—in part based on that Legion Hall experience—about Kerry’s rising fortunes in Iowa and just hope the boss wasn’t watching “Fox News Sunday.”

It turns out that Iowa’s caucus-goers had moved beyond anger at President Bush over the Iraq War to a desire to do something about it, like defeat him. As the Iraq War’s beginning diminished as a top voting issue, Kerry’s locally built organization and his sharper message turned out to be much more effective than the one Dean built over the Internet.

It’s back to the future next time. Shoe leather beats BlackBerries for getting to the bottom of the story. And next time seems to be happening earlier than we might like. The 2004 Democrats cleared out of here just two weeks ago, and now signs of the early stirring for 2008 can already be found: Rudy Giuliani was down the street last night speaking at the local chamber of commerce dinner. It was his second visit to Iowa this month.

David Yepsen is The Des Moines Register’s political columnist. He has covered Iowa politics for 30 years, and in the fall of 1989 he was a fellow at the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.