The hype is true. The changes sweeping journalism, and political journalism in particular, are fundamental. And they are irreversible. Whether this is exciting or frightening depends on your vantage point, or — as in my case — on your mood on any given day.

As a cofounder of Politico, a new publication that has placed a large bet on the business and editorial future of Web journalism, I can be a very ardent proselytizer for the new era of journalism. I am persuasive enough that, a year and a half after our launch, I run a newsroom of more than 40 people. They were recruited by Executive Editor Jim VandeHei and me to join our experiment — supported by Politico publisher Robert Allbritton — in trying to produce first-rate political journalism outside the traditional confines of a big national or metropolitan daily. So far, our bet is paying off in both traffic and revenue.

There's one point, however, I don't usually emphasize in the recruiting pitch: I never wanted a new era of political journalism. I liked the old era. What's more, it is far from clear to me that the new culture of political reporting is serving the public as well as the old one did. On some days, in some ways, it's obvious that the answer is no.

What I mean by the "old era" is the established order in political journalism that existed in 1985 — and for several decades before that, and maybe 10 years after. I choose 1985 as my personal marker because that was the year I arrived at The Washington Post as a summer intern, and then I stayed for the next 21 years becoming one of that paper's political correspondents.

In the old order, a relatively small handful of reporters and editors working for a relatively small handful of newspapers had enormous influence to set the agenda of coverage of presidential campaigns and national politics generally. Television networks, of course, had larger audiences. But the campaign narrative was shaped in basic ways by the reporting and analytical judgments of reporters for newspapers such as the Post, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal. Of course, there were a few other print publications whose influence in shaping the national political debate ebbed and flowed during the past two decades.

The people who held this influence as a rule were (and are) serious and substantive. People like reporter and columnist David S. Broder and executive editor Leonard Downie, Jr., both mentors, defined their careers above all by a sense of institutional responsibility. They knew the power of the Post platform and knew it made a big difference to the country how well they did their jobs. The country could do a lot worse than these two and the many others of that generation of journalists who shared their values.

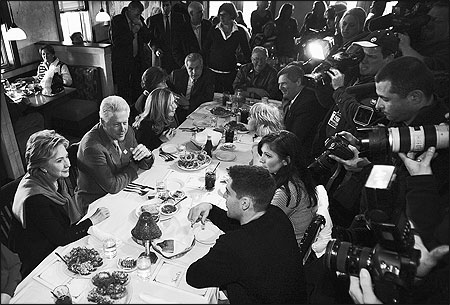

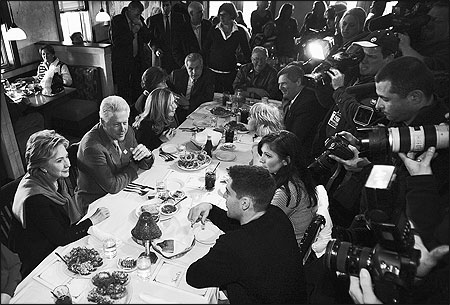

Cameras were focused on Senator Hillary Clinton, former President Bill Clinton, and daughter Chelsea during a lunch with voters at the Latin King restaurant in Des Moines, Iowa. January 2008. Photo by Christopher Gannon/Des Moines Register.

The New Order

Inheriting the old order was not an option for my generation of journalists. The Web has demolished the exclusive franchise of big newspapers to set the agenda. It has imperiled, to put it mildly, the business model by which traditional publications prospered. And it has created a whole new set of incentives and opportunities that are reshaping the profession — which reporters and publications have impact, which ones drive the conversation.

Politico was an effort to reckon with these new incentives and opportunities. There were two ideas about journalism that animated us — entrepreneurship and specialization.

Print journalism has shifted from an institutional to an entrepreneurial age. It used to be that the most important thing about a reporter was what paper he or she worked for. These days, the most influential reporters are ones who have used the power of the Web to build their individual brands. The particular platform they work — what paper or Web site — is secondary.

One example is Mark Halperin, a friend of mine and coauthor with me of a book on politics. In 2004, he created an enormous and influential audience for The Note, a daily digest of news and analysis that started as an internal e-mail at ABC News. In 2008, he's done something similar at The Page, a minute-by-minute narration of the campaign for Time.

Here's the important point. No one is going to The Page thinking, "I wonder what Time magazine's take is on today's news." They are thinking, "I wonder what Halperin's take is on today's news."

Another example is Mike Allen. Like me, he grew up covering Virginia politics (Mike at the Richmond Times-Dispatch, me at the Post.) Like me, he was someone brought up in journalism's institutional age who has chosen to cast his lot with an entrepreneurial model. After leaving the Times-Dispatch, Mike worked at The Washington Post, The New York Times, the Post again, and Time magazine, before joining the launch of Politico. At every step of the way, Mike has added to his own franchise as one of Washington's best-connected, most energetic reporters. He is a classic case of a reporter who has built his own brand.

The other great journalism trend driven by the Web is toward specialization. Increasingly, it seemed to us, readers gravitate less to general-interest sites and more to ones that place them in the middle of specific conversations they want to be a part of — whether the conversation is about stocks or stock-car racing. We knew there was a large audience of people, in Washington and around the country, who shared our interest in politics and policy, and — if the journalistic content was good — would read everything we could produce on the subject.

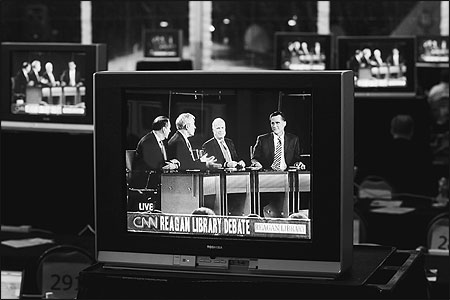

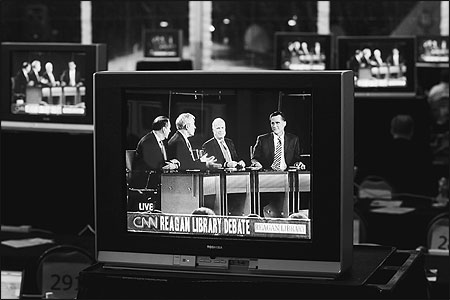

GOP candidates Mike Huckabee, Ron Paul, John McCain, and Mitt Romney appear on television monitors inside the media filing room at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library during the final debate before Super Tuesday. January 2008. Photo by Brian Baer/Sacramento Bee/McClatchy Tribune.

Political Coverage on the Web

So, is the content good — not just at Politico but also in the flood of coverage produced on the Web in this election year?

A lot of it is very good — as good or better than any the Broder generation turned out, produced in greater volume and with more speed. That speed and volume, of course, is reason for skepticism — the main reason I still wonder if the new era is really better than the old.

The big problem for journalism, vividly on display in 2008, is keeping its sense of proportion in a Web-driven era, when the best and most important coverage gets merged constantly with the lightest and most entertaining — and all of it tends to get overtaken in an instant by the nonstop news cycle.

Ben Smith is one of the most talented, most productive and, as our Web traffic makes clear, most-read writers at Politico. He is well known for some of the most perceptive analysis and biographical work on both Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. He's also the guy who broke the story, in just a few paragraphs on his blog, about John Edwards's $400 haircut. He knows the difference between what's important and what's just buzz. But can our political culture discern the difference?

I find myself stunned all the time by big stories that somehow fail to have the impact they deserve, just as I am stunned by the trivial firestorms that can consume cable news for a day or two before passing on. For a time in early 2007, Ben was a poster child for one hazard of the fast-paced nature of the Web — when for a few minutes he posted on his blog what turned out to be an inaccurate item about Edwards dropping out of the presidential race when his wife's cancer returned.

But he — and his news reporting of this story — is also a poster child for journalistic transparency. Within an hour of that error, he posted — and his editors left on the home page for 36 hours — an extensive reconstruction of how the error happened. That willingness to acknowledge error, engage with critics, and practice self-examination in public is the kind of thing that comes naturally to a younger generation of reporters (Ben is 31), who have grown up on the Web. It does not, in my experience, come naturally for the traditional big news organizations.

It is the Ben Smiths and Jonathan Martins and Carrie Budoff Browns — all among the Politico reporters under 35 whose work has stood out this election cycle — that is the best thing about this new era of Web journalism. Unlike me (at 44), they don't seem to brood about a receding old order. Instead, they plunge in, fully confident that there is a robust future for the news business. Their talent increases my own confidence that traditional values — fairness, relevance, serious devotion to good journalism's role in our civic life — can be defended and vindicated in a wild new era.

John Harris is editor in chief of Politico, at www.politico.com. He coauthored with Mark Halperin a book about presidential politics entitled, "The Way to Win: Taking the White House in 2008."

As a cofounder of Politico, a new publication that has placed a large bet on the business and editorial future of Web journalism, I can be a very ardent proselytizer for the new era of journalism. I am persuasive enough that, a year and a half after our launch, I run a newsroom of more than 40 people. They were recruited by Executive Editor Jim VandeHei and me to join our experiment — supported by Politico publisher Robert Allbritton — in trying to produce first-rate political journalism outside the traditional confines of a big national or metropolitan daily. So far, our bet is paying off in both traffic and revenue.

There's one point, however, I don't usually emphasize in the recruiting pitch: I never wanted a new era of political journalism. I liked the old era. What's more, it is far from clear to me that the new culture of political reporting is serving the public as well as the old one did. On some days, in some ways, it's obvious that the answer is no.

What I mean by the "old era" is the established order in political journalism that existed in 1985 — and for several decades before that, and maybe 10 years after. I choose 1985 as my personal marker because that was the year I arrived at The Washington Post as a summer intern, and then I stayed for the next 21 years becoming one of that paper's political correspondents.

In the old order, a relatively small handful of reporters and editors working for a relatively small handful of newspapers had enormous influence to set the agenda of coverage of presidential campaigns and national politics generally. Television networks, of course, had larger audiences. But the campaign narrative was shaped in basic ways by the reporting and analytical judgments of reporters for newspapers such as the Post, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal. Of course, there were a few other print publications whose influence in shaping the national political debate ebbed and flowed during the past two decades.

The people who held this influence as a rule were (and are) serious and substantive. People like reporter and columnist David S. Broder and executive editor Leonard Downie, Jr., both mentors, defined their careers above all by a sense of institutional responsibility. They knew the power of the Post platform and knew it made a big difference to the country how well they did their jobs. The country could do a lot worse than these two and the many others of that generation of journalists who shared their values.

Cameras were focused on Senator Hillary Clinton, former President Bill Clinton, and daughter Chelsea during a lunch with voters at the Latin King restaurant in Des Moines, Iowa. January 2008. Photo by Christopher Gannon/Des Moines Register.

The New Order

Inheriting the old order was not an option for my generation of journalists. The Web has demolished the exclusive franchise of big newspapers to set the agenda. It has imperiled, to put it mildly, the business model by which traditional publications prospered. And it has created a whole new set of incentives and opportunities that are reshaping the profession — which reporters and publications have impact, which ones drive the conversation.

Politico was an effort to reckon with these new incentives and opportunities. There were two ideas about journalism that animated us — entrepreneurship and specialization.

Print journalism has shifted from an institutional to an entrepreneurial age. It used to be that the most important thing about a reporter was what paper he or she worked for. These days, the most influential reporters are ones who have used the power of the Web to build their individual brands. The particular platform they work — what paper or Web site — is secondary.

One example is Mark Halperin, a friend of mine and coauthor with me of a book on politics. In 2004, he created an enormous and influential audience for The Note, a daily digest of news and analysis that started as an internal e-mail at ABC News. In 2008, he's done something similar at The Page, a minute-by-minute narration of the campaign for Time.

Here's the important point. No one is going to The Page thinking, "I wonder what Time magazine's take is on today's news." They are thinking, "I wonder what Halperin's take is on today's news."

Another example is Mike Allen. Like me, he grew up covering Virginia politics (Mike at the Richmond Times-Dispatch, me at the Post.) Like me, he was someone brought up in journalism's institutional age who has chosen to cast his lot with an entrepreneurial model. After leaving the Times-Dispatch, Mike worked at The Washington Post, The New York Times, the Post again, and Time magazine, before joining the launch of Politico. At every step of the way, Mike has added to his own franchise as one of Washington's best-connected, most energetic reporters. He is a classic case of a reporter who has built his own brand.

The other great journalism trend driven by the Web is toward specialization. Increasingly, it seemed to us, readers gravitate less to general-interest sites and more to ones that place them in the middle of specific conversations they want to be a part of — whether the conversation is about stocks or stock-car racing. We knew there was a large audience of people, in Washington and around the country, who shared our interest in politics and policy, and — if the journalistic content was good — would read everything we could produce on the subject.

GOP candidates Mike Huckabee, Ron Paul, John McCain, and Mitt Romney appear on television monitors inside the media filing room at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library during the final debate before Super Tuesday. January 2008. Photo by Brian Baer/Sacramento Bee/McClatchy Tribune.

Political Coverage on the Web

So, is the content good — not just at Politico but also in the flood of coverage produced on the Web in this election year?

A lot of it is very good — as good or better than any the Broder generation turned out, produced in greater volume and with more speed. That speed and volume, of course, is reason for skepticism — the main reason I still wonder if the new era is really better than the old.

The big problem for journalism, vividly on display in 2008, is keeping its sense of proportion in a Web-driven era, when the best and most important coverage gets merged constantly with the lightest and most entertaining — and all of it tends to get overtaken in an instant by the nonstop news cycle.

Ben Smith is one of the most talented, most productive and, as our Web traffic makes clear, most-read writers at Politico. He is well known for some of the most perceptive analysis and biographical work on both Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. He's also the guy who broke the story, in just a few paragraphs on his blog, about John Edwards's $400 haircut. He knows the difference between what's important and what's just buzz. But can our political culture discern the difference?

I find myself stunned all the time by big stories that somehow fail to have the impact they deserve, just as I am stunned by the trivial firestorms that can consume cable news for a day or two before passing on. For a time in early 2007, Ben was a poster child for one hazard of the fast-paced nature of the Web — when for a few minutes he posted on his blog what turned out to be an inaccurate item about Edwards dropping out of the presidential race when his wife's cancer returned.

But he — and his news reporting of this story — is also a poster child for journalistic transparency. Within an hour of that error, he posted — and his editors left on the home page for 36 hours — an extensive reconstruction of how the error happened. That willingness to acknowledge error, engage with critics, and practice self-examination in public is the kind of thing that comes naturally to a younger generation of reporters (Ben is 31), who have grown up on the Web. It does not, in my experience, come naturally for the traditional big news organizations.

It is the Ben Smiths and Jonathan Martins and Carrie Budoff Browns — all among the Politico reporters under 35 whose work has stood out this election cycle — that is the best thing about this new era of Web journalism. Unlike me (at 44), they don't seem to brood about a receding old order. Instead, they plunge in, fully confident that there is a robust future for the news business. Their talent increases my own confidence that traditional values — fairness, relevance, serious devotion to good journalism's role in our civic life — can be defended and vindicated in a wild new era.

John Harris is editor in chief of Politico, at www.politico.com. He coauthored with Mark Halperin a book about presidential politics entitled, "The Way to Win: Taking the White House in 2008."