Truth in the Age of Social Media

Verifying information has always been central to the work of journalists. These days the task has taken on a new level of complexity due to the volume of videos, photos, and tweets that journalists face. It’s not only the volume that presents challenges but the sophisticated tools that make it easier than ever to manipulate information. This issue of Nieman Reports looks at how the BBC, the AP, CNN, and other news organizations are addressing questions of truth and verification.

|

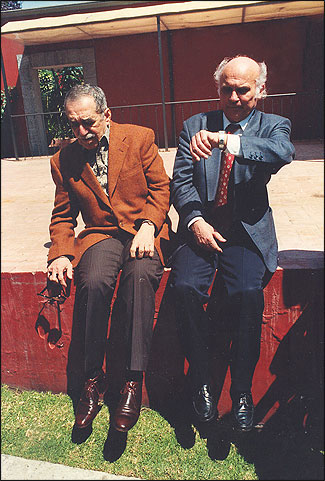

| Accuracy was a hot topic when Ryszard Kapuscinski, right, taught journalists at the invitation of Gabriel García Márquez. Photo courtesy of the Ibero-American New Journalism Foundation. |

Ryszard Kapuscinski: A Life

By Artur Domoslawski

Translated By Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Verso. 464 pages.A clumsy moment of stonewalling—self-revealing in retrospect—jars an otherwise sleek 2004 documentary about the fabled Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski: When the film's interviewer asks Kapuscinski, deferentially, about the multiple death sentences he allegedly survived while covering dictatorships and coups in the developing world, the famously mild, self-effacing writer grows defensive. He shakes his head in annoyance. In accented English, he cuts off the questioner. "I am not talking about these problems—never. Never answer these questions," he mutters. Following an emphatic pause, he adds stiffly, "Next one please."

Five years after dying from complications of cancer, Kapuscinski remains one of the most celebrated chroniclers of human suffering in our time: a solitary philosopher-reporter who was catapulted to fame by reporting from the world's danger zones, usually on the shoestring budget of the Polish Press Agency, and who shaped his daily dispatches into books of luminous prose adored by millions, among them literary giants such as John Updike and Salman Rushdie.

But in "Ryszard Kapuscinski: A Life," the journalist Artur Domoslawski strips away Kapuscinski's mythic Lone Ranger mask. And what emerges beneath is a haunting portrait of a man who felt increasingly oppressed by his legacy—a storyteller compelled by ultimate truths and deep history, yet desperate to shield his readers from manufactured elements of his own past. He died, ill and steeped in dread, still trying. "I will sell you for nothing an idea for the title of your book," a close friend of Kapuscinski sadly tells the biographer. " 'Kapuscinski—the price of greatness.' "

Tough Love

Published two years ago in Polish, Domoslawski's book ignited fierce debate in Kapuscinski's homeland, where the author of "Imperium," "The Soccer War," "The Emperor," "Another Day of Life" and other works of lyrical reportage has been elevated to the status of Journalist of the Century. Yet Domoslawski's book is a mournful expos-, and so his revelations are gently rendered. A former acolyte of the famed war correspondent, he describes Kapuscinski's improbable trajectory from a childhood of genteel poverty in a backwater called Pinsk to the glittering banquet halls of Europe and the Americas with love—albeit a tough love. He locates, for example, evidence from government files that implicates the young Kapuscinski in intelligence gathering abroad.

Many Eastern Bloc foreign correspondents were forced to collaborate with communist regimes during the Cold War. But for Kapuscinski, whose oeuvre returns again and again to ordinary people's struggles against power, the shame of cooperation was gutting. In Africa, foreign ministry officials assigned him to keep tabs on American companies and agencies. (The Polish embassies' vaudevillian code for making contact with the journalist was, "Greetings from Zygmunt." Kapuscinski's countersign was "Has he sold the car?") In Latin America the security service handlers knew Kapuscinski by his code name "Vera Cruz." By then, however, Kapuscinski had grown famous enough to push back. He pulled the freelancer's old trick of recycling articles—in this case, by presenting them as intelligence reports.

An anecdote from the early 1990s, when Poland's right-wing press was gleefully outing intellectuals compromised by the ancien régime, reveals the terrible power of this kept secret. Kapuscinski—by all accounts a gnomish, affable personality—exploded after a cocktail party where a post-communist bureaucrat glibly named Polish diplomats he thought had been Soviet agents. "How dare you, you bastard!" the writer shouted, pinning the startled official to the wall by his lapels.

"I begin to think he was crushed by fear—and not merely of revelations of his cooperation with the intelligence service," Domoslawski writes of the aging Kapuscinski's final, anxiety-riddled years. "It was about far more than that."

He is referring, of course, to Kapuscinski's controversial habit of conflating journalism and literature.

Kapuscinski himself often described his reporting method as creative: He insisted he wrote to the "essence of the matter." Domoslawski records him explaining to a colleague how tinkering with the sequence of real events is acceptable because it "sometimes helps to convey a deeper meaning. It all depends how it is done, and whether it sits within the particular realities, within the climate, or whether it is artificial, invented, deceptive."

This type of literary reportage, Kapuscinski's defenders have always noted, is rooted in an Eastern European tradition that used allegory to navigate around the culture of censorship prevalent behind the Iron Curtain. To be fair, Kapuscinski's text does brim with dreamlike imagery that clearly signals the imagination at work. An old Indian inexplicably cranks an antique gramophone in the middle of a Mexican desert. Or the inhabitants of a Siberian town stagger about in a frozen fog, leaving discernible tunnels through it. His books never include disclaimers.

Meanwhile, during his three years of research, Domoslawski unearths more fictions that have little to do with art.

It appears that Kapuscinski transferred his "magical realism" to the pages of his own life. Traveling in the great wanderer's footsteps, Domoslawski finds eyewitnesses who contradict several famous Kapuscinski-ian incidents of derring-do. It's unlikely, he concludes, that Kapuscinski faced death by firing squads in Africa or South America, as his book jacket blurbs assert. (Hence, perhaps, his evasiveness in the documentary.) Kapuscinski also appears to have grossly exaggerated his friendships with leftist liberation icons such as Che Guevara, Salvador Allende, or Patrice Lumumba. He may have never met them at all.

Domoslawski defers to a former New York Times correspondent who knew Kapuscinski to sum up such mythomania: "As the years went by, he became a member of the intelligentsia … but he came from a poor background, from the provinces, from ignorance," said the late Michael T. Kaufman. "He had to make a super-human effort and do some incredible work on himself to get to the top, to reach the position he achieved at the end of his life."

Burdened by his self-made legend, Kapuscinski died planning one more improbable journey, to the islands of Oceania, a place he had never been.

Was it an escape? His last notebook entries, written after he was hooked up to a feeding tube, still hold the master's trademark beauty, and can be read, as the best Kapuscinski always will be, on multiple levels. "A terrible feeling of helplessness, I'm losing touch with the world, with the light, with my surroundings, with reality, it's all drifting away, disappearing."

Paul Salopek is a Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent. While on fellowship at the Nieman Foundation, he researched an around-the-world journey he'll make on foot to tell the story of human migration out of Africa 50,000 years ago.