Photojournalism Dead? It's Just Changing With the Times

In the next 50 pages Nieman Reports take stock of photojournalism today. While problems are noted, the report is positive. The articles and the photo essays by 10 Nieman Fellows demonstrate the special value of pictures to news. As noted photographer Edward Steichen summed it up at the dinner celebrating his 90th birthday in 1969: “The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function.”

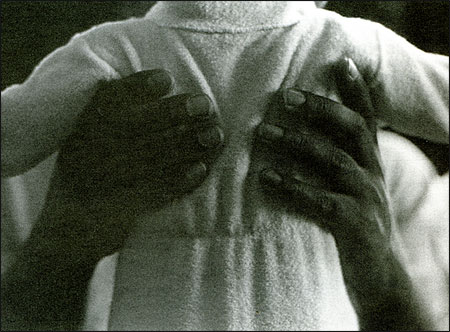

“Bill & Son, 1962,” from ”Roy DeCarava: A Retrospective.”

Roy DeCarava doesn’t occupy a space, he blends with it. But to say that his approach to photography is stealth-like is to attribute to him a potential for discord that does him a disservice. With DeCarava there is no hidden agenda; his is a harmonious presence. In his carefully composed black-and-white images of the common man, we are allowed to see the colors of shadows. Rich and evocative, they render his subjects in what one essayist calls “a reflective state of grace.”

For close to 50 years, DeCarava has consistently explored one subject, New York City, primarily Harlem. It is this community that educated and nurtured him, and provided this only child with a surrogate family among whom he always found a place at the table. To paraphrase the poet, unlike the smoke that forgets the earth from which it ascends, DeCarava never betrayed or strayed from what appears to be a solemn trust. The love and care with which he embraced this family is repaid in the access he is given to their lives. Through his images, we become part of his extended family.

DeCarava made a decision early in his career to chart his own course, “aspiring to his own values,” as he puts it. It is a decision that has cost him dearly. Both his choice of subjects and his approach to his art would put him outside the commercial loop. As a professional, he would later do a two-year stint at Sports Illustrated; it was not a match made in heaven. For a man who believes in “listening to the moment,” keeping his eye on the ball was not conducive to making good pictures.

But to suggest that DeCarava fails as a photojournalist is to confuse style with content. That he chooses to render his subject in what some consider an artistic fashion need not be taken as evidence that he abandoned the tenets of photojournalism. His pictures simply tell a story about a different black America, one that is not in a constant state of trauma. The results attest to a vision unencumbered by preconceived attitudes about his choice of subjects. Indeed, it can be argued that his pictures speak to a higher truth about his subject in a style that embraces their humanity rather than denies it.

At its best, photojournalism is simply a way of telling a story where the content of the images minimizes or exceeds the necessity for copy. DeCarava does this superbly, with an expanded, richer vocabulary. His nuances in shades of gray and black are his adjectives and adverbs used to describe his subject and their condition, his four “w’s” and an “h.” If some of us see it as art perhaps it points to an unfamiliarity with the style and language rather than tampering on the part of the photographer.

In the profession of journalism, the photographers’ contribution usually serves to augment or support the copy of the writer. It is the wordsmith who not only tells the story, but also sets the parameters for the photographer’s participation. And if anything is to be cut, it is usually the picture first. Picture magazines like Life and Look reversed that equation, and television totally changed things. DeCarava’s approach to photojournalism, and his choice of subjects, set him apart at a time when the image-makers were encroaching on the turf of the writers.

That DeCarava found greater acceptance in the salon than the newsroom says a lot about the opportunities that existed for photographers who wanted their pictures to tell their own stories. And one who selected Harlem as his beat put limits on his acceptance and his options. Ultimately, great photojournalism ends up in galleries and museums. DeCarava got there early.

“Roy DeCarava: A Retrospective” opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in January 1996. The exhibition of DeCarava’s photographs was shown in Houston and San Francisco and is currently in Atlanta. The exhibition will end its run at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington in January 1999.

Roy DeCarava was born on December 9, 1919. His parents separated long before he got to know his father. His mother encouraged him in music and the arts, and he decided at age 9 to become an artist. As a youngster, DeCarava was a latch-key child who sold shopping bags or newspapers and hauled ice. At movies, according to one writer, “he absorbed the visual aesthetic of black and white films.”

At Textile High School, DeCarava was introduced to the work of van Gogh, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. His sense of art and his possibilities exploded. He graduated in 1938 and went on to The Cooper Union School of Art. After two years enduring the frustration of racism, he continued his studies at the Harlem Community Art Center, where such luminaries as Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes were a constant presence. Artists such as Romare Bearden, Robert Blackburn, Ernest Crichlow, Elton Fax, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis and Charles White were living, breathing examples for the young black artists frequenting the center.

DeCarava shifted from painting to print-making, particularly serigraphy, and had his first one-man show in 1947 at New York’s Serigraph Galleries. He was soon making photographs to provide himself with material for his prints, and by the end of the 40’s he embraced photography as his sole medium of artistic expression.

DeCarava’s change of venue occurred around the same time that the 35-mm camera became the instrument of choice for aspiring photographers. For him, it was not a weapon, but an instrument of expression that he used, surgeon-like, to delicately expose the soul of his people. DeCarava managed to capture the everyday, seemingly mundane, experiences of his community in a way that neither stigmatizes nor romanticizes them. Many have described the womb-like darkness from which his images emerge as dark and sinister. But to me, the light comes from within, and is therefore all the more precious.

His tireless pursuit of images that speak a universal language is what makes him an important example for other photojournalists.

When I look at his images, I am reminded of why photography is noble and inherently rewarding. There is an incorrect assumption that when we look at an image we see a subject outside ourselves. Not so, says DeCarava. “The subject is not really out there, the subject is just the beginning of in here,” he says, pointing to himself. “What you’re really doing is, you’re really going inside yourself, and describing yourself and what you believe in…. Every picture that you take is another word in your bibliography of experiences. You really don’t have to find a subject; when you have a subject, the subject really reminds you of something interior, and you hang on to that because that subject opened up the door.”

Whether it’s in the photograph of “Bill and Son” or “Three Figures, Halsey Street,” DeCarava’s images speak to humankind’s determination to prevail. His still lifes live; there is hope in his abstracts; affirmation resounds in “Curtains and Light.” There is light at the end of all of his tunnels.

Lester Sloan, a 1976 Nieman Fellow, is a contributing essayist to National Public Radio’s Weekend Edition and a freelance photojournalist living in Los Angeles.