Photographer Rob Finch and I walked at one point through a shattered village where we’d met a man who had lost a son. “Some things,” Rob said, “are unphotographable.” The two-time international newspaper photographer of the year would go on to prove himself wrong. But I knew what he meant. What we were witnessing couldn’t all be contained in a frame.

So we confronted the arcane question—arcane, I mean, relative to the life and death around us and mainly of interest to journalists on deadline: How does one cover a disaster of such magnitude, a calamity that defies description? Where does one begin to extract meaning from mass destruction?

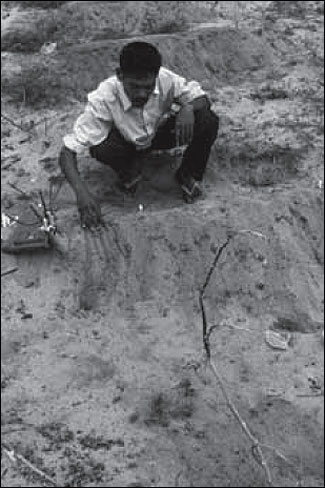

In the tiny fishing village of Palameen Madu, Iruthayanathan Justin visits the grave he dug for his oldest daughter, Jeromica. Photo by Rob Finch/The Oregonian.

Using a Tight Focus

Our answer was to focus in tight. We picked a few families, a few aid workers, a few towns. Only by seeing people up close, we felt, could readers appreciate the dimensions of the devastation. We presented these people in scenes that began to form chapters in a narrative. I tried to include details that newspaper writers often omit—bickering among aid workers, for example, or dissembling by a pilot who forgot to engage his landing gear—but that later seem to engross friends over beers. I don’t know if we succeeded, but I like to think the stories differed from pieces I used to write. They had more developed characters and more sense of place.

This disaster also differed from wars and other calamities I’ve covered. It affected an entire coastal region, leaving more than 290,000 dead or missing. It singled out children and old people unable to withstand the towering waves. It leveled whole towns, meaning journalists had to show up with survival gear, fully self-sufficient.

Like most people covering the tsunami’s fallout, Rob and I had little time to prepare. I was halfway down a central Oregon ski trail when I got word to go. Rob made the rounds of Portland outdoor stores, gathering mosquito nets, bug juice, and a water filter. We got inoculations, grabbed cash, and met at the airport, where a shipping clerk thrust a bulky Internet satellite gizmo into our hands. We stuffed the unit and its tangle of cables into oversized shopping bags. We boarded the plane with two doctors and two nurses from Northwest Medical Teams, an organization that dispatches volunteers to wars and disasters.

A 10-hour flight got us to Tokyo, where we filed a story on the team members and their motivations. Another 10-hour flight got us to Colombo, where we filed again on this aid team’s hurried preparations. A 10-hour truck ride, narrowly avoiding head-on collisions, got us to Sri Lanka’s east coast, where we filed once again, this time a story about the discord within the exhausted team.

The initial coverage might have resembled an aid-workers’ reality show. But we wanted to bring readers along with the volunteers, seeing the situation through their eyes. Like journalists, these relief workers tried to beat others to the scene. They were genuinely eager to help. They also knew that the sooner they reported progress on their organization’s Web site, the faster donations would roll in.

They hurried to begin treating survivors in the one-room schoolhouse of a fishing village near Batticaloa. The next day they worked in a camp for hundreds of homeless people. Survivors arrived with gashes, bruises, fevers and diarrhea. The doctors took the diarrhea especially seriously, watching for water-borne diseases such as cholera that could explode into epidemics. One man’s body was twisted and broken from evident torture years before in Sri Lanka’s civil war. Another man showed up weeping, with no physical symptoms. The ocean had taken his son. “He just needed someone to listen,” said Dr. Tom Hoggard, a veteran volunteer who fought back tears himself.

Later Hoggard introduced us to the Justin family. The father, a subsistence fisherman, told a horrific story of saving two of his children while losing a daughter to the waves. “Over and over,” I wrote, “Iruthayanathan Justin replays what might be the most horrible predicament a parent could face. Running desperately to save two of his children from roaring tsunami waves, he had to let a third child fall behind. His two younger daughters looked back to see a mammoth wave carry their 13-year-old sister to her death.”

Justin took us back to the family’s battered home and explained how the sea suddenly turned reddish brown, how the first wave caught him by the knees, and how the biggest black wave claimed his beloved daughter, Jeromica. He showed us the grave he dug himself. Justin cried. I did, too. But he seemed grateful that people would come halfway around the world and care enough to ask what happened.

Moments Tell Larger Stories

We had planned to follow the family until the next turn in their lives. But our editors urged us to press on for Indonesia. On Sumatra two days later, we clambered aboard a Cessna carrying dried fish to Meulaboh, a shattered coastal town southeast of Aceh province. From the air, we could see the devastation was far worse this close to the fault line. Huge swaths of land were flattened, houses exploded as if by a hurricane. Yet here and there, just as in California during the fires, a single house remained by some fluke.

Survivors’ responses varied as well. Some families stood or sat, immobilized, on the concrete pads that used to support their homes. Next door, people stacked beams, tiles and roofing. The rebuilders reminded us of barefoot Sri Lankan carpenters we had seen framing a teahouse, constructing a business on a minimal investment in nails and tea bags.

In both countries, I wrote about government officials and humanitarians struggling to cope. In Sri Lanka, I parked myself in the archaic office of a deputy governor inside a crumbling Portuguese fort. I caught the dialogue as the administrator, who had lost an aide and a stenographer to the tsunami, pressed for food deliveries to camps holding tens of thousands.

I watched as a legislator representing minority Tamils entered and browbeat the deputy governor, demanding more aid from the Singhalese-majority government. During a raucous meeting the next day, the deputy repeatedly rang a bell to quiet local officials and foreign relief workers arguing about how to run camps. The meeting made another scene in my ongoing narrative accounts.

Reporters confronted physical and emotional challenges. Writer Hal Bernton and photographer Betty Udesen, of The Seattle Times, stayed in tents next to ours at a Meulaboh school. But we never saw them; they were stuck on a boat somewhere. Betty gashed her leg, which got infected; she was evacuated to a U.S. Navy ship’s hospital, where doctors saved her leg. And I didn’t learn until later that Robert Whymant, a talented British reporter whom I knew years ago in Tokyo, had died when the tsunami wrapped around Sri Lanka.

Back in Oregon, I think of Robert a lot, and of the Justins and others we met. The Justins will be able to rebuild, replace their fishing boat and return their surviving children to school—courtesy of generous Oregonian readers moved by their plight. I won’t look at the ocean quite the same way ever again. I’ve learned on a visceral level that the sea can exceed its bounds, just as we discovered that planes can be flown intentionally into buildings.

Predictably, our satellitephone gizmo never worked. I was thankful to encounter Jocelyn Ford—another former Tokyo cohort based in Beijing for Public Radio International’s “Marketplace”—who transmitted my final story after my modem melted down. After I encountered her in that schoolyard, I watched Jocelyn sit with curious children as they arrived for class in the one room not occupied by relief workers. She smiled and laughed with them in the bright morning sun, getting them accustomed to her microphone.

The children wore red and white uniforms matching the Indonesian flag above the school. In clear voices, they sang the national anthem as they might every morning, their words punctuated by giggles as a boy yanked a girl’s hair. Jocelyn recorded it all. Her soundtrack reflected a tone of innocence and promise that I have tried to keep alive inside ever since.

The tsunami washed away four kilometers of a major commercial roadway in Sri Lanka. Photo by Rob Finch/The Oregonian.

Rich Read, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winner who covers international affairs for The Oregonian.