In recent years, journalism in Ukraine and other post-Soviet states has been in flux, with editorial independence reliant on foreign entities, funding in constant deficit, and press freedoms wavering. Now, as Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to drag on, the work of journalists in the country has become more urgent — and dangerous — than ever.

As civilian deaths mount, journalists, too, have lost their lives reporting on the war’s horrors. Nieman Reports takes a look at how Ukrainian journalists are reporting on the war in their home, the costs of reporting accurately on the invasion, and the growing threats to press freedom under Putin.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion has already cost thousands of lives, including those of four journalists. Most civilian casualties are from aerial bombardment. “It just reminds me exactly of Chechnya,” says Carlotta Gall of The New York Times. “Those terrible days in Grozny and the absolute disregard for everything.”

Russia’s urban warfare strategy is brutally simple: Surround, pound, probe, and clear. Forces try to lay siege to a city, pulverize whole neighborhoods with artillery and missiles, send in small groups to probe enemy defenses and eventually take the city street by street with tanks and infantry. “My experience of the Russians is they have no regard for civilian areas, for hospitals, for humanitarian columns, for refugees fleeing, none of that,” Gall says.

Hundreds of foreign journalists have poured into Ukraine since Russia invaded the country on February 24. Most are now concentrated in the capital of Kyiv and in the western city of Lviv, near the border with Poland. A lot of journalists haven't experienced conflict in the former Soviet Union under Russian fire, notes Gall, “and I think some of them don't quite realize how ruthless Russian forces can be.”

The first part of the Kremlin’s military playbook has already been on display in the besieged southeastern port of Mariupol. Most international journalists left the city weeks ago, but some Ukrainian reporters stayed behind.

“In Mariupol I realized that nowhere is safe,” says Ukrainian freelance photojournalist Evgeniy Maloletka, who has worked for numerous Western outlets, including the Associated Press. “Rockets can reach basements, destroy buildings, and kill people regardless of where they are hiding. Being encircled is the worst. I would highly recommend against ending up in an encircled city." Maloletka and a fellow Ukrainian journalist working for AP in the city produced an unforgettable story of the horrors of this war.

While much has been said about how Russia is employing similar tactics against Ukraine to the ones it used in Syria, journalists who have covered both conflicts say Ukraine could become even more dangerous.

“In Syria, a decade ago, I started saying, ‘Women and children are not close to the frontline, they are the frontline,’” says the BBC’s chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet. “The difference with Syria is the Syrian government, backed by Russia and Iran, gave very few visas to Western media and almost no access to the heart of the battlefield to Western media. In this war, journalists are arriving in great numbers in Kyiv and have been going to the outskirts, where control is constantly shifting between Russian and Ukrainian forces.”

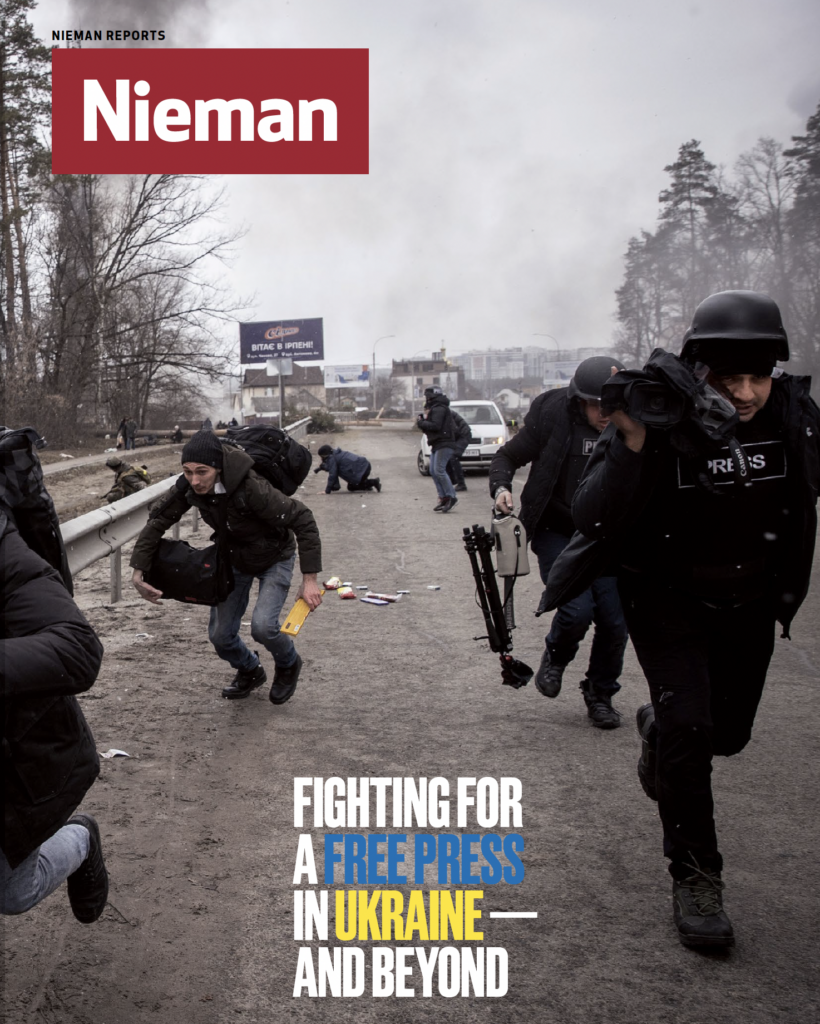

All four media deaths so far have occurred in and around the capital. News crews who have driven northwest towards the adjacent city of Irpin have come under fire. That was where U.S. filmmaker Brent Renaud was shot dead on March 13 while covering refugees fleeing Russian forces on the far side of Irpin. It is still not clear who fired on him and his colleague Juan Arredondo, who was wounded, but Ukrainian authorities blamed Russian troops.

The mayor of Irpin banned foreign journalists from visiting the city after the attack. A day later in the nearby town of Horenka, a Fox News team came under fire. Ukrainian journalist Oleksandra Kuvshynova and cameraman Pierre Zakrzewski were killed. Ukrainian camera operator Yevhenii Sakun was killed in a missile strike on a Kyiv TV tower on March 1.

If journalists cluster at the site of an attack mingling with Ukrainian civilians and military, or if they stay too long in one place, they become potential targets for Russian artillery and snipers. Photographers and videographers are particularly vulnerable since they need to get up close for pictures. Unlike in the U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, there are few opportunities for reporters to embed with the armed forces. No Western outlets are with the Russian military, of course. But even the Ukrainian regular forces have taken only a handful of foreign embeds. Consequently, international news outlets have relied partly on Ukrainian military-supplied footage and content generated by civilians on smartphones.

One foreign correspondent who did travel with Ukrainian forces is the BBC’s Quentin Sommerville who reported from besieged Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city. Sommerville covered the war in Syria from the rebel side. He said that conflict was worse for journalists but added: “At least for the moment, the threat is different. In Syria the risk wasn’t from artillery — it was that gnawing threat of kidnap. Afghanistan [was] IEDs [improvised explosive devices]. Here it’s artillery and cruise missiles which worry me.”

Another veteran of the Middle East conflict, Nabih Bulos of the Los Angeles Times, agrees: “This is early days. We haven't even begun to see the sorts of artillery and mortar barrages that can be expected once the Russian army properly unleashes its military might.”

That prospect haunts even war-hardened Ukrainian journalists.

"This time we didn't travel to a war zone. Instead war came to us, straight into our homes,” says videographer Roman Stepanovych, who worked with U.S. outlets and co-founded the independent Ukrainian outlet Zaborona. “Having families and kids here makes us vulnerable."

Some Ukrainian journalists have been covering conflict since Russia invaded the east of the country in 2014. Others have been thrust into the war. They say they need hostile environment training and protective equipment, such as anti-ballistic vests and helmets, which are in short supply globally. “As journalists we face difficulties in everything, including weak communication channels with combat units, paranoia from local residents, and lack of access to state officials,” Stepanovych says. “There's also [a] certain incompetence on the side of fellow-journalists. Not all of them know how to evaluate risks properly, have experience in hostile environments and follow journalistic ethics. I've covered Crimea, Donbas, Turkey-Syria, and Myanmar. But this war is unpredictable and deadly like no other. It's truly terrifying.”

Additional reporting by Iulia Stashevska in Berlin.

Robert Mahoney is CPJ’s executive director. He writes and speaks on press freedom and has led CPJ missions to global hot spots from Iraq to Sri Lanka. He worked as a reporter, bureau chief and editor for Reuters around the world. In 2022, he co-authored with former CPJ executive director Joel Simon The Infodemic, How Censorship and Lies Made the World Sicker and Less Free which will be published April 26. Follow him on Twitter @RobertMMahoney.