On midterm election night last year, NPR carried out its usual live coverage, coordinating stories from its reporters and from member stations across the country. Most of the audience followed along via these stations’ broadcast signals.

But those not listening to the radio could get updates, too, by asking Amazon’s voice assistant Alexa for an update on election news from the NPR One app. The response to this request was a short report with the latest news.

“Obviously, there are people that are going to be just glued to election returns,” says Tamar Charney, managing director of personalization and curation at NPR. “But we also know there’s a lot of other people who have a lot of other things going on in their life. They’re dealing with their kids, they’re getting ready for the next day, but they may still want to be able to be plugged in.”

The goal of the Alexa offering was to test two hypotheses: Would listeners find an option like this useful? And could NPR give it to them?

The answer to the second question was yes: A staff worked until about 3 in the morning to make updates available twice an hour.

But as to the first question, whether listeners would find it useful—it’s not clear how many found it at all. NPR won’t say how many people tried listening to the news this way, but, then again, the original commercial radio news broadcast in 1920 didn’t draw a massive audience either. “It was our first time trying this out and it was successful because we developed a workflow and best practices for election night so that we are ready for the volume of listeners we will get in the presidential elections in 2020,” Charney says. (Disclosure: While reporting this story, I was on the staff of the show “1A,” which is distributed by NPR and produced by member station WAMU. I am now a senior editor at the station.)

At least 21 percent of Americans own a voice-activated smart speaker—Amazon’s Echo is the most popular, while Google, Apple and other tech companies make such devices, too. And sales are climbing: In 2017, only seven percent of Americans owned smart speakers. Meanwhile, radio ownership and social media use are dropping. The speakers and the artificial intelligence that powers them can replace or augment the functions of a radio or phone. By voice, users can ask their smart speaker assistants to play music, find recipes, set timers, or answer basic questions.

The simple request of asking voice-activated smart speakers for news has the potential to challenge the foundations of radio

Users can also ask for news. And this simple request has the potential to challenge the foundations of radio, turning broadcasts into conversations, changing the stories people hear, and creating individualized streams of information.

Smart assistants have long been a feature on mobile phones, but with smart speakers proliferating in homes and the technology coming pre-installed in cars, voice is pushing to the final corners of consumers’ connected lives, creating new habits and leading users to rethink how they interact with their devices. And news outlets are racing to find a place on the platform. “If [voice] does become an ever more dominant interface, then it will probably have quite profound effects on the way that information and content is consumed,” says Mukul Devichand, executive editor of voice and AI for the BBC.

For many publishers, there’s not much question if voice will grow. The question is whether news will grow with it.

The low listenership to the NPR One election night experiment relative to the NPR broadcast can in part be attributed to the lack of people currently asking their smart speakers for news. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that just 18 percent of American smart speaker owners ask for news every day—this typically involves saying,“What’s in the news?” or a similar phrase and getting back short newscast-style reports from a publisher or publishers of the user’s choice. Podcasts didn’t fare much better: Only 22 percent of American smart speaker owners used the devices to listen to podcasts, according to the Reuters Institute report.

But podcasts and newscasts aren’t designed to be played via voice command. Radio news bulletins are broadcast at specific times, usually with weather, traffic and other soon-to-be-outdated updates. In podcasting apps, shows compete for eyes before ears—attractive art and episode titles have been found to boost listening for NPR’s shows, according to Charney, and “asking people to choose without those cues seems like a nonstarter.”

Asking a speaker for news is straightforward, but it can be frustrating in its own way. Echo owners, for instance, can stack up several updates from different publishers and hear them back-to-back. This can lead to hearing the same story told by different outlets in different ways, possibly at different volumes. There might be sponsorship messages at the end of each publisher’s briefing. Depending on when the user asks, the stories may not have been updated recently. And local offerings are scant. A user who asks for a news update early in the morning could hear three outdated stories followed by yesterday’s weather report.

However, it is possible to get broadcast quality news from a smart speaker: Users just need to ask their device to play a radio station. This is something smart speaker owners have taken to.

The Reuters Institute report notes that more than twice as many people in the U.S. listen to radio on their smart speakers than ask for news every day. And public radio stations have noticed an increase in traffic to the online streams of their live broadcasts. NPR reported that, in the first quarter of 2018, across the entire system of member stations, smart speakers made up about 16 percent of streaming though some stations have seen even more. For KCUR in Kansas City, Missouri, smart speakers accounted for 38 percent of online streaming for a week this January. Mobile phone and desktop computer streaming were each under 30 percent.

For many publishers, there’s not much question if voice will grow. The question is whether news will grow with it

KCUR digital director Briana O’Higgins says these are mostly new listeners to the stream, not people who switched from streaming on their phone to streaming on their speaker. (Data is not yet available to indicate whether smart speakers are replacing listening to analog radio.) O’Higgins attributes the numbers to an on-air campaign encouraging KCUR broadcast listeners to ask their smart assistants to play the station.

KCUR has not invested heavily in creating content exclusively for smart speakers, but the rise in streaming has given the live broadcast a new relevance, and speaker listening at home is playing a role in programming decisions. The station recently moved the interview program “Fresh Air” to an early evening time slot. O’Higgins says the potential for people to listen to the show’s longform conversations on smart speakers as they cook dinner wasn’t the primary reason for the move, but it was discussed. On top of this, some stations have found that listeners who turn on the livestream with their speakers stay tuned in for longer.

“The actual speaker has become a radio replacement product. It is taking the place in people’s homes, the physical location where radios had been—next to the bed, on the kitchen counter, in the living room,” Charney says. “People are now turning to it, I think, to do some of the things they had used the old device, i.e. radio, to do.”

“Play this radio station” is one of the more primitive—albeit intuitive—commands for a smart speaker. As people get familiar with their devices, and as publishers start designing news updates that take advantage of smart speakers’ unique capabilities, streaming could wind up being a transitional behavior. “I think we’re at early days of the general public even thinking of asking for news from a voice assistant,” Charney says.

If the stream gives way to on-demand news on smart speakers, then public radio—or any radio stations offering smart speaker streaming—will have a lot of company on the platform. The list of available flash briefings for the Amazon Echo already includes not only radio outlets but TV networks, print publications, and websites. There are even updates delivered entirely by synthetic voices. “Our organization is very focused on us delivering the news where our audience is, and there is no question that audio is a growing segment of where audiences expect to find news,” says Kelly Ann Scott, the vice president of content for the Alabama Media Group, which manages several publications in Alabama and is owned by the national media chain Advance Local.

Alabama Media Group is working on briefings and updates for voice platforms. The challenge is figuring out what, exactly, users expect to hear, and how it should sound. “When you put your own user hat on and really think about what do you want from these voices that are coming through the speakers in your lives, you can learn a lot,” Scott says.

The Alabama Media Group’s website AL.com has a flash briefing, “Down in Alabama,” hosted by local journalist Ike Morgan. As he runs through the top stories of the day, his casual delivery and Alabaman accent make him sound more like an informed neighbor than a stentorian newscaster. “It has an incredible sense of place,” Scott says of the update, which is also available as a podcast. “That kind of authenticity makes it authoritative, too, when he’s talking about the news. It’s not talking at people. He really treats it like he’s having a conversation with his listener.”

NPR and Google are working separately on news experiences designed specifically for voice

Similarly, on midterm election night, Charney’s team prepared reports for Alexa with the aim of making them sound distinct from a traditional newscast. They didn’t want asking for news to be the same as turning on a radio. “It’s subtle sometimes but there’s a difference between going on the air and giving a report on something and responding to a question,” she says. “Newscasts are a little more presentation, and what we were aiming for is a more genuine answer to a question.” Charney says the goal is to have updates sound more like the “engaging, compelling, human-to-human answer” that an actual person would give, rather than a machine playing back something recorded for millions of people to hear at the same time.

NPR and Google—maker of the second-most-popular smart speaker in the U.S.—are working separately on news experiences designed specifically for voice; they’re open-ended and designed to travel with users wherever they find themselves near a voice device, which is to say, everywhere. Each one is a feed of audio stories curated largely by algorithms that learn a user’s preferences over time.

NPR has been doing this, absent voice commands, since 2011, when it introduced its Infinite Player, later rebranded as NPR One. The app starts with a newscast consisting of a few short stories. The pieces tend to get longer the more a person listens, with news from local public radio stations interspersed where available. Since the beginning, NPR One has been compared to the music service Pandora, which learns listeners’ preferences and plays them music they’re more likely to enjoy.

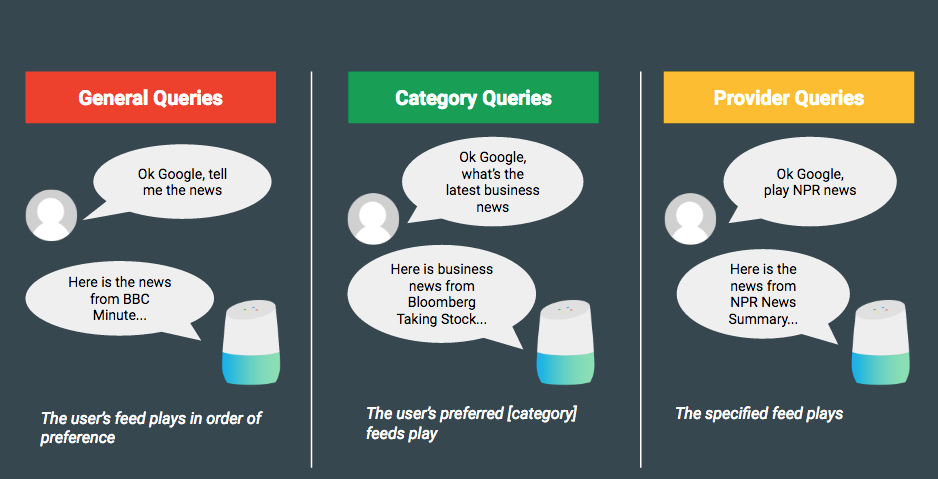

The service Google is developing and testing, called News on Google Assistant, is similar. It uses the Google News algorithms to curate a stream of stories from a variety of news organizations, in and out of radio. Like with NPR One, the feed starts with short pieces and expands to longer stories as listening continues. Its aim is to serve content based not only on user preferences, but also on which stories are the most important in their area, and which ones listeners have already encountered on other platforms.

These feeds cater to voice by removing the need for a listener to ask for a specific station or source each time they want an update (though NPR One still needs to be requested by name). There’s also no need to search through a smartphone application to change settings for news playback, either. The experience is analogous to turning on a radio or opening a news app—with an endless feed of information. Both News on Assistant and NPR One end up sounding something like a radio newsmagazine. But unlike a radio show, “it’s contextually relevant and it’s dynamic,” says Steve Henn a former radio journalist who is now the content lead for audio news at Google.

These products are currently built to respond to a generic request like “what’s in the news” or “play NPR One.” But that’s not the only way Charney and Henn imagine users asking their speaker for news.

Voice could lead to a burst of creativity around traditional beats, or it could lead to stories that don’t connect with audiences vanishing

In an example Henn uses, a listener in California could ask about the bankruptcy of local utility company PG&E and hear a piece from a local news outlet. “In the future you could ask a topical news question and get a story,” Henn says. The technology could also someday allow a user to interrupt a story to get more information—“Alexa, who is this speaking?” “Hey Google, tell me more about PG&E.”

This would require at least two changes: Platforms would need to allow news outlets’ voice apps (called “skills” on Alexa) to respond to questions like this (or users would need to ask these questions of a specific news outlet); and news organizations would need to make sure that voice assistants can find their content and play it as an answer to specific questions.

Already, Google has published instructions for marking up text to point its search engine to the most relevant, newsy information in stories, which can then be read aloud by Assistant’s synthetic voice. For audio to be discoverable by a search engine and played back in response to questions, sound files would need to be indexed and tagged. Speech-to-text technology could also transcribe entire stories for search engines. And this could lead to an even more significant change to audio content than voice alone.

With data on search terms from thousands of users flowing in, audio producers could cater their work to the questions users ask or the topics they most commonly search for when they’re expecting an audio reply. This is common practice for text-based outlets, but new territory for radio producers. Search metrics are more immediate and precise than any other audience data audio producers currently have: Radio ratings take weeks to compile, and while website stats might indicate which topics are popular, they don’t correspond directly to what an audience is willing to listen to. Some radio newsrooms have developed popular series based on answering questions listeners send in; making audio discoverable through search could amplify these efforts. But there are hazards to basing editorial strategy entirely on data. What if no one searches for news on City Hall, for instance?

“Data can be abused,” says Brendan Sweeney, director of new content and innovation at KUOW public radio in Seattle. “And it’s simultaneously true that the myth of a journalist’s or an editor’s gut being the all-supreme thing, that’s also problematic.” The challenge, Sweeney says, is not to assume listeners avoid entire topics, but to instead look at the data more closely to see if something else might be turning them away. “If an important story isn’t finding the audience it deserves, we need to adapt how we tell that story. Experiment with leads, framing, tone, etc.,” Sweeney says.

The most successful ways of telling stories in an algorithmically curated, voice-based news feed will be determined by user data. And many producers are experimenting now to see what works. NPR One provides stations with information on when in a story listeners decide to skip to the next option. Google’s news product could offer similar information, and it’s being developed and tested in partnership with a working group of publishers convened by Google.

Knowing questions users ask and granular details of users’ listening habits could drive audio producers to make stories that almost perfectly fit listeners’ habits and preferences. Conventions of storytelling and production that are common practice could change. Experiments could lead to new standards. However, until the data that could lead to these changes is widely available, the standard radio-style report will likely dominate. For its as-yet-unreleased stream, Google advises producers to keep their stories either under two minutes or between two and 15 minutes, and to make pieces sound-rich by including multiple voices and natural sound, techniques found in abundance on news radio.

Voice could lead to a burst of creativity around traditional beats, or it could lead to stories that don’t connect with audiences vanishing. With algorithmic feeds, though, it’s not just editors who decide which stories users hear. Reporters may experiment with their framing and writing for City Hall stories, but what’s to ensure that they’ll end up in streams that are out of a news outlet’s control?

Henn says the algorithm driving News on Assistant, which surfaces stories of local importance and isn’t based on internet virality, is designed in part to fight filter bubbles, rather than let them build if users skip past certain stories. “Our goal is to provide a diverse range of news, views, and opinions from as wide a variety of authoritative sources so that users can develop their own critical thinking on a story or subject,” he says.

If Alexa tells you it’s true, check it out

And NPR One has “an algorithm that offers other points of view to people who consume a lot of partisan podcasts,” Charney says. “Human curation is a big part of what we do both to better inform and manage what the algorithm is doing, but also at times to ensure that certain stories aren’t subject to any personalization.”

Amazon declined to comment on whether it was planning any kind of algorithmic news product, but said the decision of what makes it into a flash briefing remains up to the user: “We don’t consider Alexa a news outlet, we consider Alexa a conduit for the news—meaning we have hundreds of news sources customers can choose from and we leave that up to them on what they’d like to hear.”

Even if algorithms and journalists keep users’ best interests in mind, listeners could still end up getting slanted coverage through their smart speakers. Voice platforms are no more immune to trickery than any other platforms, and in some ways, they can be more vulnerable. The technology to create “deepfake” videos that show people doing and saying things they never did or said is developing. But the ability to re-edit, impersonate, or synthetically reproduce a person’s voice is already here. In 2016, Adobe showed off a potential new feature in its Audition audio editing application that would allow editors to create new words and phrases from a sample of a person’s voice. The demonstration involved creating new phrases from existing conversations. (It hasn’t yet been commercially released.)

Completely synthetic voices play a large and growing role in voice technology, too. Smart assistants speak in them, and some news organizations are using text-to-voice technology for their news briefings. Quartz, for instance, uses two computer voices to deliver a few minutes of news every day. The text is drawn from the Quartz smartphone app, which is written as a series of conversational text messages.. Voice simulation has improved to the point that John Keefe, Quartz’s technical architect for bots and machine learning, says some users have told him they prefer the machine narration for short updates. “The voices are getting better and better,” he says. “It’s very clear to me that they’re just going to get to the point of human clarity. And probably better.” At the moment, Henn says his data shows machine voices are less engaging than humans. And machines can’t replace the humans who are quoted in stories, and whose voices convey information not just with words, but through tone and timbre.

To maintain trust, identifiers for the source of each story in a voice news feed will be key. Currently, this happens at the beginning of flash briefings. It’s possible for a malicious actor to try and put a fake NPR skill in these devices’ app store, but Amazon certifies new submissions to its flash briefing skill. And the company says it regularly audits available skills on its platform and reviews reports of “offensive or otherwise inappropriate content.” On algorithmic feeds, like the one Google is planning, the identification of a source becomes an issue of sound design and programming. Google’s specifications for creating news for Assistant include an introduction that identifies both the publisher and the person speaking.

To keep the sources on their platforms accurate, Henn says Google continues to research the origins and spread of fake news. The company is also working on using the same technology that creates deepfakes to recognize them, and they’ve invited developers to submit tools to do the same.

There’s also a possibility that false information could spread not through news designed for speakers, but simply from falsehoods posted online. One feature of smart speakers is their ability to do quick web searches and return information—“how tall is the Empire State Building?” for instance. This gets complicated when users ask about news that’s still developing. The Reuters Institute found that asking for the death toll in the 2017 Grenfell Tower Fire in the U.K. led to different answers from Amazon’s and Google’s devices, because they were drawn from different sources. These answers eventually changed to be the same, correct number, though Alexa was not forthcoming about its source, according to the report.

Building trust between a voice and a listener is a challenge publishers and platforms are working to solve

Whether smart assistants can be fooled by false information is a test of how they search for data—if they draw from Wikipedia, it could be edited or faked, while if they draw from other web sources, their algorithms will have to be capable of properly sourcing information. Keefe says trusting a speaker depends on how savvy a listener is, and their willingness to ask it for the source of a fact. He compares it to “the journalist adage: If your mom tells you she loves you, check it out.”

If Alexa tells you it’s true, check it out.

Building trust between a voice and a listener is a challenge publishers and platforms are working to solve. And there’s also a question of trust between the two. As voice develops, publishers are again finding themselves relying on big tech companies to distribute their content, along with the content of their competitors.

The ease of using a voice device is partly due to it simplicity: Only one answer comes back in response to a question and there’s no need to look at a screen (though smart speakers with screens and voice-activated televisions are available). However, this limits how voice platforms can present news, and how much of it they can present. A user may ask for an update on a big story, but rarely does only one news outlet cover a story. Voice assistants will have to figure out how to respond if a user asks “what happened in the Russia investigation” and every national news outlet has a story. “On big stories it’s inevitable that we are going to have multiple partners covering the same event. In that circumstance we will be guided by what’s best for the users,” Henn says. “Often what is best for the user is giving them a choice. We are working on this but today for topical news queries we give users multiple stories on the requested topic and also offer to send them to their phone.”

Increasingly, the story that’s surfaced could be a local story. Google’s working group of publishers testing News on Assistant includes a handful of local outlets. “Already roughly half of our content comes from local sources,” Henn says. “When there are local stories that are nationally significant hearing from a local reporter can add a tremendous amount of context and expertise to a story.” NPR One data shows that listeners who hear a local newscast are more likely to return to the app.

This could be promising for local journalists who are increasingly fighting for space on global platforms. But an algorithm deciding when to play a story, or distributing stories without paying for them, raises familiar fears of tech companies choosing winners and losers in journalism.

“There’s a long history and I think the skittishness is natural,” Henn says. “Until we lay out a clear monetization strategy publishers are going to be worried.” Henn declined to say what this monetization strategy looks like, in part because it’s still being developed. And that development is happening in a partnership between Google and publishers, through the News on Assistant working group. “Ultimately this product will succeed if it works for our partners,” he says.

For monetization, Henn notes that voice creates the opportunity for interactive ads, and Google offers a way for listeners to tell their speakers to donate to nonprofit newsrooms after they hear a story. While flash briefings for Alexa often feature a sponsorship message at the beginning or end of an update, Henn says “we can’t have a call for support after every one-minute-long story, so we’re working on ways to smartly deliver these messages to Assistant users.”

Radio producers moving toward voice have room to experiment in these early stages

One term that’s used in these conversations is “offramp.” It’s a way for users to leave the main feed of stories and build a deeper relationship with publishers whose work they find most valuable. This could mean hearing a feed of just one outlet’s stories, opting into an email newsletter, or simply following them on social media. From there, publishers can try to convert these followers into subscribers, donors, or possibly advertising targets. “The piece we control is this single piece of audio. What all publishers want to have more influence on is what happens during, before and after the listener hears that single piece of audio,” says Tim Olson, the chief digital officer of KQED (another Google working group member, which has also received money as part of the Google News Initiative).

For skittish publishers, the rewards beyond revenue remain valuable. Forming a relationship with people on their speakers in the kitchen may make it easier to form a relationship with them on their headphones and in their cars. Working with tech companies now means shaping a growing platform; it’s a rare opportunity for publishers to exert some control over a technology they don’t own.

Radio producers moving toward voice have room to experiment in these early stages. Their primary audiences remain tuned in to the old devices: More than 90 percent of American adults listen to radio each week. Public radio ratings have never been higher. This might not last. And promotions for smart speaker skills are showing up between stories in radio news as smart speakers become another type of furniture in more and more American homes. It’s not guaranteed the people in those homes will ask for news. But for now, publishers and tech companies are preparing, so if anyone does ask, they’ll have an answer.