In recent years, journalism in Ukraine and other post-Soviet states has been in flux, with editorial independence reliant on foreign entities, funding in constant deficit, and press freedoms wavering. Now, as Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to drag on, the work of journalists in the country has become more urgent — and dangerous — than ever.

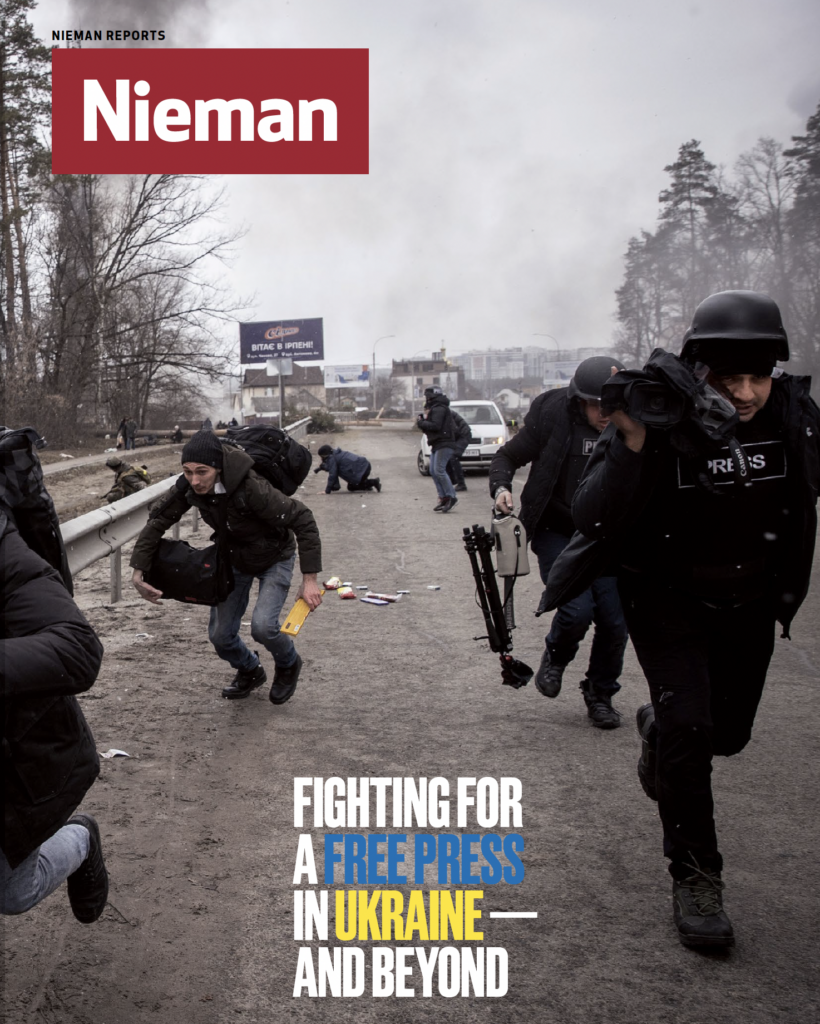

As civilian deaths mount, journalists, too, have lost their lives reporting on the war’s horrors. Nieman Reports takes a look at how Ukrainian journalists are reporting on the war in their home, the costs of reporting accurately on the invasion, and the growing threats to press freedom under Putin.

This came a day after the independent TV channel Dozhd announced a temporary suspension of its operation in its broadcast on March 3. “We need strength to exhale and understand how to continue. We really hope that we will return on air,” said General Manager Natalia Sindeeva. At the end of the broadcast, Dozhd streamed Swan Lake, a reference to the August coup of 1991, when all Soviet TV channels played the ballet on repeat instead of showing images of the coup, becoming a symbol of suppression of truthful information.

Over the course of just one week, the independent media landscape in Russia has been shuttered, returning the country to the pre-Perestroyka state without any semblance of a free press. Russian media regulator Roskomnadzor has blocked access to several independent media outlets, including MediaZona, Meduza, Nastoyashee Vremya, The New Times, Doxa, The Village, and Tayga.Info. Russian prosecutors justify the move by accusing the outlets of purposeful and systematic dissemination of “false information about the essence of the special military operation.” But, they were accurately reporting news of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. Many international media corporations, including CNN, BBC, Bloomberg News, ABC, CBS News, and Radio Liberty, have been forced to suspend operations in Russia.

The new law curbing what journalists can say about the military is essentially censorship of what journalists can say about the invasion of Ukraine. Any data on casualties or information on the resistance the Ukrainians are mounting could be considered “fake information.” Under the legislation, truthful reporting of the conflict is nearly impossible.

“It has been decided to eradicate journalism entirely and to put all disagreeable behind bars,” said Sergey Smirnov, the editor-in-chief of MediaZona, an independent investigative outlet. “Even if you don’t say anything [about the war], it might not save you if they [the Russian government] don’t like you.”

Controlling the narrative is particularly important for the Russian government amid the lack of support for the war and the growing dissent in the country. The invasion of Ukraine coincided with the new trial of Alexei Navalny, the opposition activist who rose to international prominence after being poisoned with a nerve agent. Accused of stealing donations from his anti-corruption foundation, Navalny could face an additional 15 years in prison. Navalny’s allies, who continue to produce livestreams on YouTube debunking state propaganda, believe the timing of the trial is not random. As Navalny said in a recent Instagram post, “We will circumvent blockages until the internet functions in Russia. And if it gets blocked, we will be using Morse code to deliver news to you.”

For years, independent media in Russia have reported on corruption, protests, and politics, reaching their audiences online often through social media. The daily number of subscribers of news channels on Telegram, a cloud-based messaging app, has grown by an estimated 3.5 to 5 million per day since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, according to TGStat.ru, a non-profit project that tracks the platform. But social media is not immune to state control and state propaganda, and the online news environment is often used to amplify confusion and misinformation.

Tech companies are under pressure from both sides of the conflict, which can result in questionable decisions that further aggravate the situation for independent outlets. Echo Moskvy, an independent radio station controlled by Russian state-owned company Gazprom-Media, reported being suspended by YouTube and Twitter even though the outlet maintained editorial independence and provided truthful reporting. Coincidentally, on March 3, the board of directors of Echo Moskvy decided to liquidate the outlet and, according to its editor-in-chief Aleksey Venediktov, after Russian officials blocked its website over its reporting on Ukraine. Its dissolution is symbolic as the Russian government’s decision to spare the outlet from repression until now helped maintain at least a façade of freedom of press in the country.

Without independent media, the Russian public will become hostage to the state narrative about “the special operation” aimed at “de-nazification” of Ukraine, as Moscow describes its war against the country. In fact, the use of the word “war” to refer to the conflict in Ukraine is prohibited in Russia. In the alternative reality of Russian propaganda Zelensky’s government has lost control over the country after giving weapons to the neo-Nazi groups that use combat drugs. “Without drugs people cannot shoot at their own citizens,” said Russian political expert Sergey Karnouhov, a common guest commentator, on state-run TV channel Rossiya 24 on March 5. “They [neo-nazis in Ukraine] use Captagone, just like ISIS fighters,” he falsely added, while showing unverified footage from Syria.

To the domestic public, the crackdown on independent press is falsely presented as an exodus of traitors who have been misinforming the Russian public for decades. “Western media allege that there is no journalism in Russia, but in reality, they just need to abide by the Russian laws,” said one presenter on Rossiya 24 on March 5. He then reminded the audience that it was Germany and France that blocked the Russian international TV station RT, widely viewed as a government propaganda vehicle.

Apart from state control, independent outlets that rely on crowdfunding also struggle with the consequences of the economic sanctions, introduced by the U.S. and the E.U. in response to the invasion. “How can we survive,” said Smirnov in a Telegram post. “Due to the shutdown of Russian banks and the blocking of MediaZona, donations are starkly shrinking.”

Blocked independent outlets will continue to fight for their right to report through the courts. However, the situation will only intensify as the war in Ukraine goes on. With many journalists fleeing Russia, independent reporting is still possible from abroad. And local audiences can use VPN connections to access blocked sites and social media. But without international support free press in Russia will not survive, and the isolation of the Russian audience will continue. “Right now, independent journalism can survive only outside of Russia,” said Smirnov. “Inside the country compromises are no longer possible.”