How are great journalists made? Often, it’s pieces of great journalism that help form them, influencing their lives or careers in an indelible way. To celebrate the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 80th anniversary in 2018, we asked Nieman Fellows to share works of journalism that in some way left a significant mark on them, their work or their beat, their country, or their culture. The result is what Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski calls “an accidental curriculum that has shaped generations of journalists.”

“What a Fraternity Hazing Death Revealed About the Painful Search for an Asian-American Identity” was the article that broke me wide open. I was born and raised in Malaysia, but I have lived here in the United States for nearly 10 years now—and given that I’ve married an Idahoan, it’s almost certain that I’ll spend the rest of my life in this strange land. As such, I’m going through the peculiar process of trying to fit the narrative of my life within the wider scheme of American life. This is, of course, a challenging proposition on any level, but I’ve found it particularly difficult to grapple with the contextual terms of my ethnicity: I’m Asian, but not Asian American. I belong to a racial minority, but one whose narrative doesn’t factor much within broader conversations about race in America. I’m an immigrant in search of upward mobility, but one who shares blood with people from a nation on a complicated rise. (I’m ethnically Chinese.) All this amounts to a simmering... let’s call it emptiness, one I did not fully recognize I felt until I read Kang’s painful, searching, and relentless feature on what these Asian kids did to themselves in the pursuit of a larger narrative for their identities, which remains so agonizingly far from clarity.

The article gave voice to an American narrative that I, for the very first time, identified with. And it feels like armor against the emptiness.

What a Fraternity Hazing Death Revealed About the Painful Search for an Asian-American Identity

By Jay Caspian Kang

The New York Times Magazine, Aug. 9, 2017

Excerpt

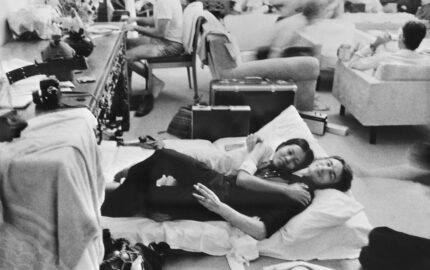

Asians are the loneliest Americans. The collective political consciousness of the ’80s has been replaced by the quiet, unaddressed isolation that comes with knowing that you can be born in this country, excel in its schools, and find a comfortable place in its economy, and still feel no stake in the national conversation. The current vision of solidarity among Asian-Americans is cartoonish and blurry and relegated to conversations at family picnics, in drunken exchanges over food that reminds everyone at the table of how their mom used to make it. Everything else is the confusion of never knowing what side to choose because choosing our own side has so rarely been an option. Asian pride is a laughable concept to most Americans. Racist incidents pass without prompting any real outcry, and claims of racism are quickly dismissed. A common past can be accessed only through dusty, dug-up things: the murder of Vincent Chin, Korematsu v. United States, the Bataan Death March and the illusion that we are going through all these things together. The Asian-American fraternity is not much more than a clumsy step toward finding an identity in a country where there are no more reference points for how we should act, how we should think about ourselves. But in its honest confrontation with being Asian and its refusal to fall into familiar silence, it can also be seen as a statement of self-worth. These young men, in their doomed way, were trying to amend the American dream that had brought their parents to this country with one caveat: I will succeed, they say. But not without my brothers!

Jay Caspian Kang © 2017 The New York Times.