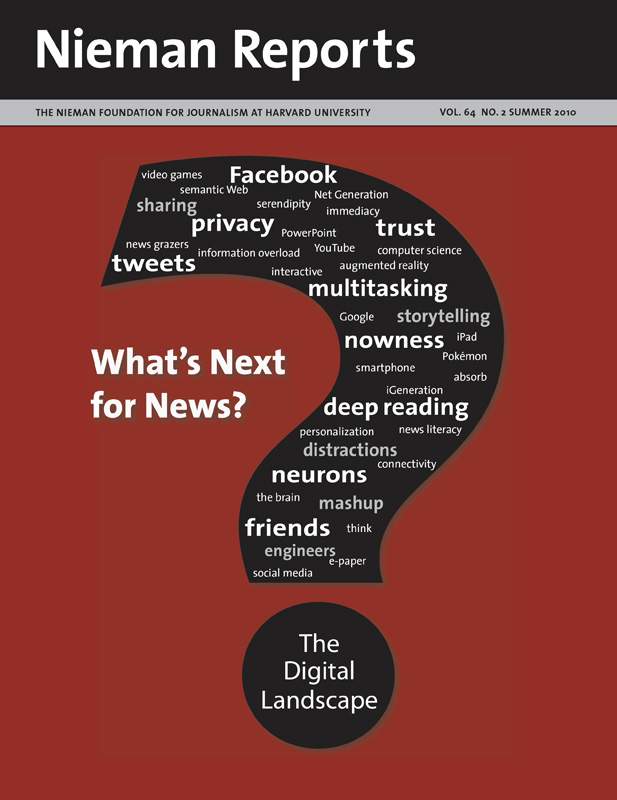

The Digital Landscape: What's Next for News?

Explore the emerging realms of digital territory where news and information reside—or will soon. It’s a place where game playing thrives and augmented reality tugs at possibilities. It’s where video excels, while the appetite for long-form text and the experience of “deep reading” is diminished, and it’s where the allure of multitasking greets the crush of information. Learn how young people negotiate their journey, and travel inside the brain to discover its capacities in the digital realm. Dig deeper into topics covered in the magazine by clicking on the books in our digital library to reveal selected videos, articles, blogs and Web sites.

“People who are citizens in an information age have got to learn to think like journalists.”—Kathy Kiely, USA Today reporter and News Literacy Project fellow

The News Literacy Project was conceived when I discovered that I could speak to my daughter’s sixth-grade classmates about my job without embarrassing her.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Critical Thinking About Journalism: A High School Student’s View"

- Lucy ChenIn 2006, I spoke to 175 students at Thomas W. Pyle Middle School in Bethesda, Maryland about what I did as an investigative reporter for the Los Angeles Times and why journalism mattered. Julia’s hug told me that I had succeeded with her; the thank-you notes that followed told me that I had connected with her classmates.

Concerned with both the implosion of the news business and the challenges posed to Julia’s generation by the explosion of news and information sources, I began to think about the prospect of journalists, both active and retired, teaching students in classrooms across the country how to sort fact from fiction in a digital world. Two years after talking with those sixth-graders, I exchanged my 29-year newspaper career for a new journalistic mission.

That germ of an idea has evolved into a national program that recently completed its first full year in the classroom. In the 2009-10 school year, the News Literacy Project worked with 21 English, history and government teachers in seven middle schools and high schools in New York City, Bethesda and Chicago, reaching nearly 1,500 students. More than 75 journalists spoke to students and worked with them on projects.

We provide original curriculum materials that we adapt to the subject being taught. Whatever the underlying subject matter, our curriculum focuses on four pillars:

- Why does news matter?

- Why is the First Amendment protection of free speech so vital to American democracy?

- How can students know what to believe?

- What challenges and opportunities do the Internet and digital media create?

I hired Bob Jervis, the former head of social studies for the public schools in Anne Arundel County, Maryland to work with me to develop the curriculum materials. They are built around more than 20 engaging activities dealing with topics as diverse as viral e-mails, Google and other search engines, Wikipedia and the news. Some can be done by teachers, some by journalists, and some by either. Teachers choose the ones that best fit their classes.

Some teachers have done the unit during just a few weeks; others have embedded it in their coursework throughout the year. They deliver it in three phases: initial activities and the introduction of our “word wall” of basic journalism and news literacy terms and concepts, presentations by two to four journalists to each class, and a culminating hands-on student project.

We train the journalists to concentrate on our four pillars, to use anecdotes and activities to engage the students, and to include extensive time for Q. and A. and discussion. Our local coordinators work with the journalists to plan their presentations and to connect them in advance with the teachers.

Our goal is to give young people the critical thinking skills to be better students today and better-informed citizens tomorrow. We also want them to appreciate quality journalism and to use it as the standard against which to measure all information.

One of our pilot projects was at Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, where we started with Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. government classes in the spring of 2009. This past school year we added English classes and reached about 625 students in the ninth, 10th and 12th grades.

“This is nirvana for me,” English teacher Marilee Roche said. “I’d give up ‘Hamlet’ for this.”

I’ve spent a lot of time in classes at Whitman. It’s been exhilarating to see journalists connect with students and spark lively discussions about such issues as identifying bias, assessing fairness, and verifying information, whether for a research paper or an investigative report.

I’ve also learned a great deal about the students’ own consumption habits, biases and views. They get a lot of information from social media or friends. Few read newspapers (either online or in print, even if their parents subscribe to one). Many don’t follow the news at all and most aren’t aware of the watchdog role of the press in a democracy. Before exposure to the project, few had any idea of the kind of reporting and vetting it generally takes to get a story into print or on the air.

I’ve also observed widespread distrust of the mainstream media. Students often feel that all journalism is driven by bias—political, commercial or personal. The students themselves frequently fail to distinguish between news and opinion in a media culture where those lines are increasingly blurred.

My experience has underscored the importance of the project’s mission. Former colleagues and others have launched worthy efforts to find new ways to fund and deliver journalism in the digital age. But that is not enough. Without a demand for quality journalism (on any platform) from the next generation, what future will it have?

So, what does a news literacy lesson look like? Here are some snapshots:

- Gwen Ifill of “The PBS NewsHour” and “Washington Week” explaining how she handles bias: “I hope you never know what I think. I’m there to provide you the information so you can decide. I have to keep open the possibility that the other guy has a point. … I have to be an honest broker.”

- Sheryl Gay Stolberg of The New York Times describing how she spent the entire previous day nailing down a single name: that of the third gate-crasher at the infamous state dinner that President Barack Obama hosted for the prime minister of India at the White House in November.

- Peter Eisler of USA Today discussing accountability: “Never trust anybody who doesn’t admit they make a mistake. Never trust anyone in life who doesn’t admit they make a mistake.”

- James V. Grimaldi of The Washington Post asking students what they knew about a shooting that had occurred near the school the previous evening, then pressing them on how they had learned this information, whether they believed it and why.

In one memorable presentation, Brian Rokus, a CNN producer, showed the students video excerpts from a report he did with Christiane Amanpour about the New York Philharmonic’s trip to North Korea in 2008.

The students got a glimpse of a country without First Amendment protections of free speech. They saw the minders who shadowed the tightly restricted American journalists. Rokus also passed around a copy of The Pyongyang Times with its full-page paeans to the nation’s “Dear Leader.”

He then handed out an Associated Press report of a speech that President Obama had made to Congress and asked the students to cross out everything they would censor if they were the editor of The Pyongyang Times and Obama was the “Dear Leader.”

Sometimes the lessons begin even before the journalist arrives. Prior to her visit, NPR ombudsman Alicia C. Shepard asked the teacher to ask the students to find out everything they could about her. When Shepard asked the students what they had discovered, one named the street on which she lived, another said she taught at American University and a third said she had attended her high school reunion. All three statements were wrong.

Two student videos from the News Literacy Project:

“Check It Out”

“Students as Teachers”“You absolutely have to check out all information and make sure it’s accurate,” Shepard said. She then shared the journalistic maxim “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” (We’ve created our own “Check It Out” button with our logo that we ask teachers to present to students when they complete our unit.)

At times, our brand of authentic learning literally brings journalistic history into the classroom. Former Los Angeles Times foreign correspondent Tyler Marshall recalled the emotional scene when he covered the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. He then picked up and displayed two pieces of the wall that he had carried home. The students gasped.

At the end of our unit, we ask teachers to assign a hands-on project to demonstrate real understanding. Options include creating a newspaper, holding a mock press conference, or preparing an oral history.

The students at Whitman created a video, song, online game, board game, and other projects that reflected what they learned about news literacy—and presented it to the class. They showed that they absorbed the project’s lessons and can find creative ways to collaborate and share them with their classmates.

As Colin Mealey and Adam Schefkind, two of the students, sang in their final project, “Wikipedia Rap”:

It’s really important to know what to believe.

You gotta know where and why and what to read.

Search your information and check it twice.

’Cause getting it wrong will come at a price.

Alan C. Miller is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former investigative reporter with the Los Angeles Times. He is the founder and executive director of the News Literacy Project.