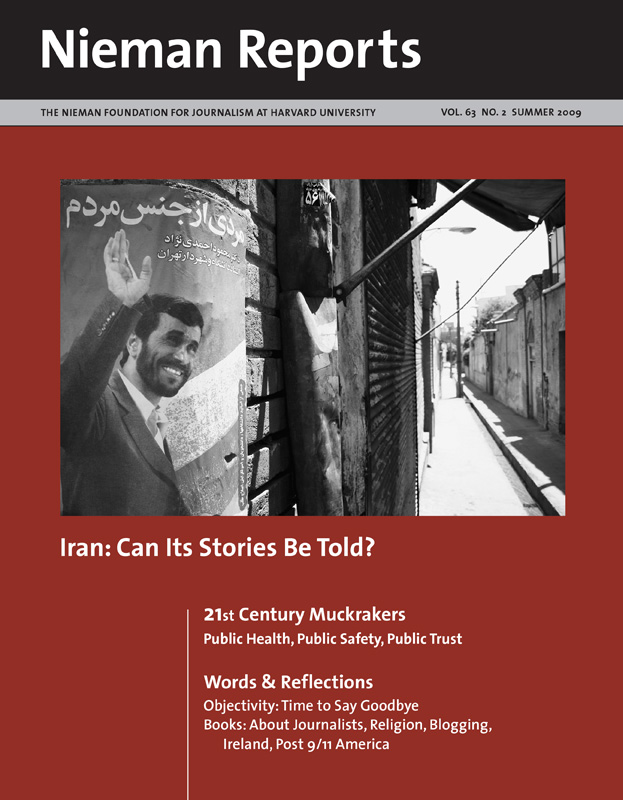

Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?

Journalists — Iranians and Westerners — share their firsthand experiences as they write about the challenges they confront in gathering and distributing news and information about Iran and its people. Their words and images offer a rare blend of insights about journalists’ lives and work in Iran. In the fifth part of our 21st Century Muckrakers series about investigative and watchdog reporting, the focus turns to coverage of issues involving public health, safety and trust. And in Words & Reflections, essays touch on objectivity, religion, blogging, Ireland and post 9/11 America.

Crosses in a makeshift memorial to the Sago miners. Photo by Ed Reinke/The Associated Press.

In September 2009, The New York Times published their own investigation on these issues, "Clean Water Laws Are Neglected, at a Cost in Suffering." When federal regulators sued Massey Energy in May 2007 for thousands of water pollution violations, the initial press coverage was a bit confusing. At first, the lawsuit was described as a major action: Massey operations across Southern West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky had violated their permitted water pollution limits more than 4,500 times over a roughly five-year period. The suit alleged nearly 70,000 days’ worth of violations on dozens of Clean Water Act permits. One analyst estimated the potential fines at more than $2.4 billion. However, by early the following week, news reports had already begun to downplay the case, citing Massey’s belief that the suit would ultimately have “no material impact” on the company’s finances.

Whether the Massey suit was a landmark case against a coal giant or a minor blip on a big company’s radar screen, what was buried in one of the follow-up reports was the grist of a much bigger story. Reporters were rightly asking the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) why the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—instead of the state—was taking this legal action against Massey. Tim Huber, an Associated Press business writer, quoted a DEP spokeswoman, Jessica Greathouse, as saying that the agency had “at some point” stopped reviewing monthly discharge monitoring reports filed by coal companies.

“Discharge monitoring reports weren’t looked at on a regular basis to determine if there were violations being reported, and we weren’t catching them,” Greathouse told the AP. “We have not done that, though we are doing that now.” She and other DEP officials told me the same thing. As she said this, I remember doing a double take: What? DEP isn’t looking at the discharge reports. This was the real story that needed investigation.

To understand why, some background is required. Discharge monitoring reports (DMRs) are a key part of the Clean Water Act. Any entity that receives a permit to legally pollute rivers and streams must file a DMR every month that lists their permitted discharge limits and the amount they actually dump into the water. This self-reporting process is the main way that regulators keep track of whether coal companies and other industries comply with their permits. If DEP officials were not bothering to even review the reports, how many violations were going uncorrected and unpunished?

There is no shortage of media attention as Richard Strickler, assistant secretary of the Department of Labor and director of the Mine Safety & Health Administration, speaks at the entrance to the Crandall Canyon Mine, August 17, 2007, in Huntington, Utah. The desperate underground drive to reach six trapped miners was suspended indefinitely after a catastrophic cave-in killed three rescuers. Photo by Jae C. Hong/The Associated Press.

Digging Into the Story

Scott Finn of West Virginia Public Broadcasting caught onto this issue right away. Finn did a follow-up radio story in which Randy Huffman, director of DEP’s Division of Mining and Reclamation, admitted his agency hadn’t been reviewing coal industry discharge reports for five to six years. “If the state isn’t even looking at the DMRs, it has no enforcement program,” environmental lawyer Jim Hecker of the group Public Justice told Finn. “It’s like trying to catch speeders by having the police sit in their cars at the police station.”

I wanted to dig deeper to find out how bad this problem was. How many violations had DEP missed? How many water quality problems hadn’t been fixed? How much in fines had the industry avoided paying? These seemed like pretty simple questions. But DEP’s records were in such poor shape that even the agency’s best computer technicians weren’t able to put together very solid numbers. Their best estimate: more than 25,000 violations missed. Some staffers predicted the number could be much higher; others guessed it was lower.

With another industry in another state, this sloppiness might seem like an outrageous situation. But in my nearly 20 years of covering the coal industry in West Virginia, this kind of thing has become all too common. Critics call the coal business an “outlaw” industry, and sometimes it’s hard not to see their point. Violations of rules created to protect the environment, not to mention health and safety regulations, are not unusual in the coalfields. Yet media coverage of these problems is sporadic; historically it is tied to major disasters.

Unfortunately, the consequences of the press turning its watchful eye away from what is (or is not) happening behind the scenes have been all too visible in recent years. For example, on January 2, 2006, an explosion ripped through the Sago Mine, a small underground operation in north-central West Virginia. Thirteen miners were missing. Twelve were found dead after a more than 40-hour search that got nonstop television coverage. The New York Times, CNN and the rest of the national media pack parachuted in to cover the story. Most of the coverage focused on the human drama. But a few reporters picked up on the hundreds of previous violations at the Sago Mine and the meager fines handed down by the U.S. Mine Safety & Health Administration (MSHA).

For example, Thomas Frank at USA Today wrote that the federal government levied a larger fine ($550,000) for the 2004 Super Bowl showing of Janet Jackson’s breast than it did for the 2001 deaths of 13 Alabama miners in one of the deadliest mine disasters in a quarter-century. “And the $435,000 fine against mine operator Jim Walter Resources was cut by a judge to $3,000,” Frank wrote in February 2006.

Journalists I talked with were shocked by the previous fines at Sago, often just $60 per violation, less than some speeding tickets they’d gotten rushing to cover breaking news. Those hundreds of violations and minimal fines at Sago weren’t unusual; coal industry officials seem to treat them simply as a part of doing business. One company’s public relations person complained to me that I didn’t provide the “proper context” when I wrote that one of his firm’s mines had 300 or 400 violations in less than a year. (It is true that underground coal mines are inspected much more frequently than most other American workplaces. At large underground operations, “resident inspectors” are virtually in residence.) MSHA inspectors are required to examine all underground mines “in their entirety” at least four times a year. No other industry has such a requirement. While routine to the industry, the consequences of these violations are anything but that to the families of dead and injured coal miners—all of whose names I know and all of which my newspaper publishes.

The Schean family’s lake house, which they had spent the past four years restoring, was the first home to be hit by the massive coal sludge spill at the TVA Kingston Fossil Plant in Harriman, Tennessee. Photo by © 2009 Antrim Caskey.

Learning From Data

After the Sago mine explosion, I spent six months examining coal mine safety as part of an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship. With time to dig in ways I can’t in the daily tug of reporting, I did read every coal mine fatality investigation report for the 10 years (1996 to 2005) and obtained related electronic data from MSHA, none of which fully tracked the findings of these death reports. So I built a database in Microsoft Access, typing in company names, descriptions of accidents, and investigation findings. I made sure to include every fallen miner’s name to help me remember that this was about people and not a bunch of numbers.

Once assembled, my database provided new insights into stories I needed to tell. The figures reminded me that disasters like Sago are rare. Most coal miners die alone crushed by heavy equipment, ground up by runaway machinery, or buried beneath collapsed mine roofs. And almost always, coal miners die because the companies they work for break the law. In nine out of 10 fatal coal mining accidents I examined, the deaths could have been avoided if mine operators had complied with well-established and longstanding safety rules.

And what kinds of punishments were handed down for these renegade operators? For each miner killed, agency officials assessed a median fine of $4,250. But fines are lowered or thrown out by judges. MSHA settles for less to avoid legal fights. Companies go belly up and don’t pay, or MSHA does not aggressively pursue payments. In some cases, appeals are still pending for deaths that occurred years before. In cases in which fines were issued and not appealed, I found that coal operators have paid a median fine per miner death of $6,200. But fines were not issued in nearly a quarter of the cases, and decisions on fines had not been made for a few deaths from 2005. If all of the 320 miners’ deaths during this decade are counted, the median fine paid by coal operators is $250 per death.

Stories Get Told

I wrote about all of this in a story, “One by One,” as part of a series we published called “Beyond Sago: Coal Mine Safety in America.” This was certainly not the first time The Charleston Gazette had exposed such behavior by the coal industry. My colleague and mentor Paul J. Nyden has been examining renegade coal contractors, corporate shell games, and industry workers compensation scams since I was in high school.

EDITOR'S NOTE

Ward wrote about his mountaintop mining reporting in the Summer 2004 issue of Nieman Reports.It was 10 years ago that I did my first major coal industry project, in which I applied the tools of investigative reporting to tell the story of mountaintop removal coal mining. By learning in-depth about the regulatory structure and reading through hundreds upon hundreds of pages of permits, I was able to point to specific loopholes, inactions and oversights by regulators. I discovered how state and federal regulators approved dozens of mountaintop removal permits without the required reclamation variances and did not—as mandated by federal law—include plans for post-mining development of flattened land.

Then, in July 2005, residents near the Raleigh County town of Sundial were upset about plans by Massey Energy to build a new coal silo as part of a plan to increase capacity of a coal processing plant located adjacent to Marsh Fork Elementary School. Part of the processing plant is a huge coal waste dam that towers above the school, just up the hollow. West Virginians remain wary of such impoundments, still recalling the day in February 1972, when one failed and flooded Buffalo Creek, killing 125 people.

Area residents and activists held protests and wrote letters. Ed Wiley, a grandfather of a student at the school, staged a sit-down protest on the state capitol steps, trying to get the governor to block the project. Apparently, no one bothered to look at the DEP-approved permit for the silo. After visiting with Wiley one morning at the capitol steps, I drove across town to DEP headquarters and went to the mining department’s file room. On earlier visits there, I’d reviewed mountaintop removal permits by looking through mounds of paper files. Now, with digital records, it took me about 15 minutes to pull the right digital video disc, find the proper maps, and see that Massey was building the silo outside of its original permit boundary—in violation of a federal law that requires a buffer zone between mining operations and schools or other public buildings.

I reviewed a few earlier versions of the map, submitted by the company over the years as mining progress reports. I printed some and took them to a local blueprint shop to have them transferred to transparencies. With these, I could easily show how the company had slowly expanded its permit boundary over the years—without asking for DEP permission and without agency officials even noticing. What these maps showed is that the enlarged permit area was just big enough, and shaped just perfectly, to allow the new silo to fit inside the legal boundaries. Within a week, I was meeting with top DEP officials and showing them my transparencies. In response, they revoked the silo permit, an action that remains in litigation today.

Lots of local media reported on the Marsh Fork controversy. But no other reporter took the time—or perhaps knew how—to go to look at permits to see if DEP was doing its job. Turns out that even though coal is “king” in West Virginia, few reporters here and in Appalachia (or in other regions of the country) follow the coal industry or know much about mining. During our round-the-clock coverage of the Sago disaster, reporters at the Gazette unwound from the intensity of our work on this story with bouts of laughter as TV anchors butchered mining terms or in other ways demonstrated their ignorance of the industry that provides half of the nation’s electricity. A well-known cable news reporter told the governor during Sago that he didn’t realize miners still went underground to dig coal.

The national media had another chance in August 2007, when a huge underground mine cave-in trapped six workers at the Crandall Canyon Mine in Utah. Early in the coverage of this mine disaster, I thought nobody had learned anything from Sago. Initial wire service reports from Utah relied on comments from company President Bob Murray, who said the cave-in was caused by a natural earthquake and not any problems at the mine itself. Coal industry watchers knew this was nonsense. The mine had experienced a “bump” or a “bounce,” a phenomenon where the weight of the earth above the mine walls collapses them. The bump at Crandall Canyon caused a spike in seismic activity, not the other way around.

Some of the press coverage was excellent. Seth Borenstein, one of the AP’s national science writers, picked up on the “bump” issue and did a fantastic story that explained the accident happened as the company had workers doing “retreat mining,” or pulling out the very coal pillars that held up the mine roof. For his trouble, Borenstein was singled out by Murray for criticism during one of the repeated rants in which the TV media—without questioning his words—allowed him time to rail against unions and blame God for the mine collapse.

Readers of the nearby Salt Lake Tribune were fortunate to have longtime coal industry reporter Michael Gorrell and his colleague, Robert Gehrke, covering Crandall Canyon. Gorrell covered Utah’s last coal-mining disaster in 1984 and with Gehrke did a heroic job of uncovering various missteps by Murray Energy and by MSHA officials charged with policing the company.

After Crandall Canyon, my mine safety reporting continued. In September 2007, I discovered that MSHA had not completed the required quarterly inspections at a Mingo County, West Virginia mine where a worker was killed in a roof fall. I found the same thing later that month after another mining death. Given this, I pulled computer records for dozens of mines across southern West Virginia and found that MSHA was way behind on its mandated inspections. Eventually, the agency had to admit the problem was widespread and seek additional money from Congress to pay inspectors overtime to catch up.

Then, in January 2008, a tip from inside MSHA led me to learn that the agency had not assessed mandatory fines for thousands of mine safety violations by coal companies. Again, MSHA was forced to admit the problem and come up with a plan to try to fix it. Both of these stories revealed that federal officials were simply not meeting even their most basic duties under the federal mine safety law.

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Read Ward’s Nieman Watchdog post »And then late last year, a huge coal-ash impoundment in East Tennessee collapsed, sending a huge flood of toxic power plant waste out over homes, fields and streams. This event got the national media—The New York Times and The Associated Press—paying attention to coal ash. But some coalfield reporters, such as James Bruggers at The (Louisville) Courier-Journal, had already been writing about it.

Role for Journalists

What does my experience with the coal mining story tell us about journalism and, in particular, watchdog reporting? These days as blogging, sending Tweets, and connecting with one another through social media seems to be replacing the roles that newspapers used to play, journalism appears to be losing its capacity to perform this core function. While my job of doing watchdog reporting about the coal industry is a lot easier because of digital records and the new technologies that help me dig for information, my concern is whether these tools will be used in the public interest. Will there be journalists with the skills and resources needed to keep an eye on powerful interests? Mortgage lenders, investment banks, hedge funds, and government officials who regulate them come to mind as topics that were ripe for inspection but regrettably didn’t receive enough of it. For people too busy getting kids off to school, paying the mortgage, and taking care of grandparents to be able to monitor such entities themselves, there must be some way that this essential task we’ve called journalism can continue to play this vital role.

Ken Ward, Jr. has reported on coal industry issues for nearly 20 years at The Charleston Gazette, West Virginia’s largest daily newspaper. He is a three-time winner of the Edward J. Meeman Awards for environmental reporting, one of the national journalism awards given by the Scripps Howard Foundation. In 2006, he spent six months studying coal mine safety as part of an Alicia Patterson Fellowship.