Some years ago, before the ill-fated presidential election of 2000, a woman I’d met at a breakfast meeting of political activists in Miami Beach called me to complain about the way ballots were counted. She was the sort of person all journalists have in their lives—a single-minded proponent of her cause whose sanity might be in question. I don’t remember her name.

But I sure remember the conversation. “You’ve got to investigate the way they count ballots,” she said. “We’re being cheated.” I said I couldn’t believe that was true. “Just go into the room where they run them through the machines,” she responded. “The air is full of little bits of paper. It’s like snow. Those ballots are being changed.”

At the time, I had no idea what she was talking about, though of course everyone now would realize she was talking about the infamous chads of punch card ballots and the way they flew off the punch cards as they were passed through the counting machines. I couldn’t imagine that anything serious was happening to the ballots. If there were such a problem surely our elected officials would have taken note long ago.

So who was crazy?

We now know that punch card balloting is a terribly flawed technology. While the snowfall of chads my caller described was not exactly the problem, it was symptomatic of a balloting system that couldn’t be counted on always to record precisely what a voter intended. Chads can fall off, hang on, refuse to be punched through. My caller was right: Every ballot a chad dropped from was altered forever, and no amount of examination in the future would let us know how the voter had meant to vote. And some chads would never drop off, and no one could ever be certain whether the voter had wanted them to or not.

If any of us had bothered to research the subject thoroughly prior to November 7, 2000, we would have known that questions about the accuracy of punch card balloting had been around since the technology was introduced in the 1960’s. A federal report even had warned of the problems, and if we at The Miami Herald had been more on the ball, we would have known that some election officials in South Florida had been pushing for the money to replace the system, but were turned down regularly by their elected bosses. Obviously, the system didn’t need replacing if it had elected them.

Fast forward to 2004. In Florida, California, Georgia and Maryland, the punch card ballot is gone. Maryland and Georgia have statewide computer voting systems, as do most of the largest cities in Florida. And while punch cards are still being used in at least parts of 22 states, according to the Election Reform Information Project, a tracking effort sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts through the University of Richmond, steps are being taken to upgrade balloting systems throughout the country.

Problem solved? Well, not exactly.

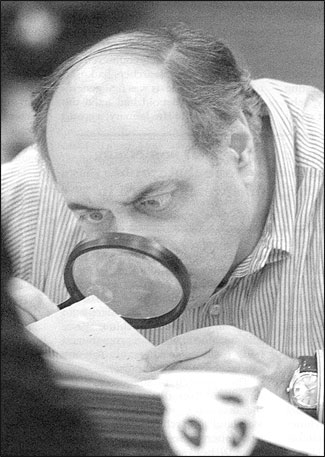

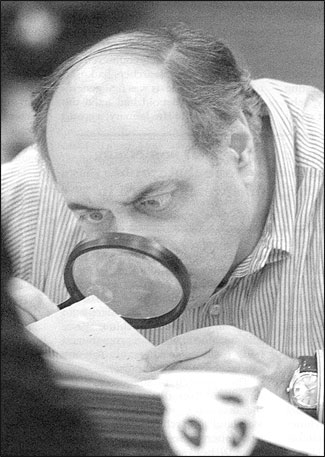

An official examining one of the ballots questioned by the canvassing board in Broward County, Florida, during the contested 2000 presidential election. Photo by Walter Michot/The Miami Herald.

Touchscreen Voting

It turns out the touchscreen voting systems that are replacing punch cards may also be prone to error or tampering. And unlike the punch card, which could be physically looked at to see if the voter’s intent can be divined, there’s nothing to look at in many of the touchscreen systems. Sure, state laws may call for recounts in close elections, but when the voters’ preference is recorded as an electric pulse on a silicon chip, what is it exactly that you recount? The best you can do is simply rerun the software; unless the machine’s hardware is flawed, you’ll get the same answer.

The problem is not merely theoretical. Already in Florida (South Florida, no less) the downside of touchscreen voting has been given concrete expression. On January 6th of this year, voters went to the polls in northwest Broward County to fill a vacant seat in the state legislature. There were seven candidates in the race. Touchscreen machines manufactured by Election Systems & Software (ES&S) were used, and the winner won by 12 votes.

Unfortunately, the results showed that 134 voters who went to the polls didn’t actually record a vote in the election. With so close a result, the second-place candidate called for a recount of the ballots—something that Florida election law also required. The candidates, election officials, party representatives, and reporters gathered a few days later in the warehouse of the elections supervisor to review the ballots. As reporter Erika Bolstad noted in The Miami Herald, there was an eerie sense of déjà vu.

Here was what was different: There were few actual ballots to look at—a handful of absentee ballots. Since most of the voting had occurred electronically, the best election officials could do was simply run the counting program again. It came up with the same result.

And the ballots of the 134 voters who recorded no vote at all? Florida law requires that such ballots, known as “undervotes,” be reviewed individually. That requirement was the result of the Election 2000 controversy in which Democrats demanded that the ballots be looked at to see whether some of them might have been obvious attempts to vote for Al Gore, but simply hadn’t been counted by the machines. Republicans opposed that effort, saying most of those ballots were probably cast by people who just didn’t want to vote in the presidential elections. The battle was waged in courts for days and ultimately was the issue that the U.S. Supreme Court seized on to stop the Florida recount, citing the lack of statewide standards for judging the validity of a partially punched ballot.

To its credit, the Republican-dominated Florida legislature realized that it was unfair to voters not to examine a ballot before concluding that it shouldn’t count and so after Election 2000 it made mandatory the physical inspection of any “undervote” ballot. But when it came time to carry out the legislative mandate in the Broward County State House race, there was nothing to examine. The results stood.

So why weren’t the voting intentions of 134 citizens recorded? There are two theories. The first, laughably put forward by ES&S officials in an election in which there was no other issue on the ballot, was that those voters simply weren’t interested in casting a ballot in that race. Later, they suggested a different reason: The voters had failed to press the red “vote” button, per instructions, after reviewing their choices, and election officials at the polls, who are instructed to press the button before clearing the machine for the next voter, failed to do so. So as in Election 2000, the failure of a vote to be recorded was laid to voter error or, possibly, to election staff error.

Not surprisingly, machine error is not suggested, either by ES&S, which would have no interest in suggesting its system might fail occasionally, or by elections officials, who had just spent $17 million to buy the machines. Yet as we all know, computers sometimes don’t do exactly what we ask them to do, and if there was one thing I came away with from the Herald’s review of presidential ballots in Florida in 2000 it was this: Voters don’t go to the polls, in a presidential race or any other, with the intention of not voting. While many of the punch card ballots bore no signs of a presidential preference, I am convinced that was the result of machines that hadn’t been properly maintained.

There’s a push now in Florida, and in many others states, as well as in Congress, to require that touchscreen voting machines provide a paper printout stating the preferences of a voter. The printout would become the ultimate check of the voter’s preferences. Nevada and California require such printouts now. Other states should.

There is another issue about touchscreen voting machines that is more difficult to resolve, however, and the debate over it is an important one for journalists to follow. Just how secure are the machines themselves from tampering?

Much of the attention on this issue has involved machines manufactured by Diebold, Inc. of North Canton, Ohio. Maryland and Georgia have chosen Diebold machines as their balloting system statewide, and other states are using them in some jurisdictions. Last July, university security experts accused Diebold of not having enough security safeguards in the software to make sure that hackers, or people with more malevolent motives, could not tamper with the results.

Diebold immediately countered that the software the researchers had used to conduct their tests was first generation and that Diebold had fixed the problems. But in late January, a group of security experts hired by the Maryland legislature issued a report that found that Diebold software still didn’t do enough to prevent outsiders from tampering with the machines. They said machines could be reprogrammed fairly easily to make a vote for one candidate count for another.

The researchers suggested some temporary fixes that would increase the machines’ security in time for Maryland’s March primary and the November general election—something Diebold saw as an endorsement of its system. Diebold noted that if there was no tampering the tests showed the machines accurately tabulated votes. Hurrah.

Reporting on Voting

But the fact that we are about to head into a new election, with the likelihood of another close presidential race, with balloting systems that either are known to be flawed (punch cards in 22 states) or are largely untested and likely to be flawed (touchscreens) is an unnerving prospect, at best.

Is there anything that can be done now? Probably not. The hopeful sign is that the balloting in the few primaries held as I write this have had few problems. Dan Seligson, the editor of electionline.org, the Web site of the Election Reform Information Project, says he’s gotten few reports of serious difficulty. Missouri’s voting has at this writing been the biggest test so far and that went smoothly, though, as Seligson noted, it also wasn’t close.

And there’s another hopeful sign. News media interest in the actual process of balloting seems to be high. Seligson says reporters are talking to him on a regular basis about balloting issues. “There seems to be a much greater awareness” of the potential for problems. “They are hungry for information.”

Let’s hope so. Voters who are informed by an aggressive and interested news media will be forewarned about possible problems and make certain they don’t occur. Thinking back on that call I got about the flurry of paper in the Miami-Dade County ballot counting room, I always will wonder if there was something I as a journalist could have done that would have changed the way ballots were counted in the 2000 election. Maybe not.

But with so much on the line, every one of us should make certain that the basic right to vote, and to have our votes counted, is not thwarted because of simple errors that could have been corrected. That means paying attention not just to whom people are voting for, but also the kinds of machines they are voting on, the procedures by which those votes are counted, and the safeguards in place to make sure the results of close contests can be verified.

To do otherwise would, in fact, be crazy.

Mark Seibel, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, directed The Miami Herald’s review of disputed Florida ballots after the 2000 presidential election. He is managing editor/international in Knight Ridder’s Washington bureau.

But I sure remember the conversation. “You’ve got to investigate the way they count ballots,” she said. “We’re being cheated.” I said I couldn’t believe that was true. “Just go into the room where they run them through the machines,” she responded. “The air is full of little bits of paper. It’s like snow. Those ballots are being changed.”

At the time, I had no idea what she was talking about, though of course everyone now would realize she was talking about the infamous chads of punch card ballots and the way they flew off the punch cards as they were passed through the counting machines. I couldn’t imagine that anything serious was happening to the ballots. If there were such a problem surely our elected officials would have taken note long ago.

So who was crazy?

We now know that punch card balloting is a terribly flawed technology. While the snowfall of chads my caller described was not exactly the problem, it was symptomatic of a balloting system that couldn’t be counted on always to record precisely what a voter intended. Chads can fall off, hang on, refuse to be punched through. My caller was right: Every ballot a chad dropped from was altered forever, and no amount of examination in the future would let us know how the voter had meant to vote. And some chads would never drop off, and no one could ever be certain whether the voter had wanted them to or not.

If any of us had bothered to research the subject thoroughly prior to November 7, 2000, we would have known that questions about the accuracy of punch card balloting had been around since the technology was introduced in the 1960’s. A federal report even had warned of the problems, and if we at The Miami Herald had been more on the ball, we would have known that some election officials in South Florida had been pushing for the money to replace the system, but were turned down regularly by their elected bosses. Obviously, the system didn’t need replacing if it had elected them.

Fast forward to 2004. In Florida, California, Georgia and Maryland, the punch card ballot is gone. Maryland and Georgia have statewide computer voting systems, as do most of the largest cities in Florida. And while punch cards are still being used in at least parts of 22 states, according to the Election Reform Information Project, a tracking effort sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts through the University of Richmond, steps are being taken to upgrade balloting systems throughout the country.

Problem solved? Well, not exactly.

An official examining one of the ballots questioned by the canvassing board in Broward County, Florida, during the contested 2000 presidential election. Photo by Walter Michot/The Miami Herald.

Touchscreen Voting

It turns out the touchscreen voting systems that are replacing punch cards may also be prone to error or tampering. And unlike the punch card, which could be physically looked at to see if the voter’s intent can be divined, there’s nothing to look at in many of the touchscreen systems. Sure, state laws may call for recounts in close elections, but when the voters’ preference is recorded as an electric pulse on a silicon chip, what is it exactly that you recount? The best you can do is simply rerun the software; unless the machine’s hardware is flawed, you’ll get the same answer.

The problem is not merely theoretical. Already in Florida (South Florida, no less) the downside of touchscreen voting has been given concrete expression. On January 6th of this year, voters went to the polls in northwest Broward County to fill a vacant seat in the state legislature. There were seven candidates in the race. Touchscreen machines manufactured by Election Systems & Software (ES&S) were used, and the winner won by 12 votes.

Unfortunately, the results showed that 134 voters who went to the polls didn’t actually record a vote in the election. With so close a result, the second-place candidate called for a recount of the ballots—something that Florida election law also required. The candidates, election officials, party representatives, and reporters gathered a few days later in the warehouse of the elections supervisor to review the ballots. As reporter Erika Bolstad noted in The Miami Herald, there was an eerie sense of déjà vu.

Here was what was different: There were few actual ballots to look at—a handful of absentee ballots. Since most of the voting had occurred electronically, the best election officials could do was simply run the counting program again. It came up with the same result.

And the ballots of the 134 voters who recorded no vote at all? Florida law requires that such ballots, known as “undervotes,” be reviewed individually. That requirement was the result of the Election 2000 controversy in which Democrats demanded that the ballots be looked at to see whether some of them might have been obvious attempts to vote for Al Gore, but simply hadn’t been counted by the machines. Republicans opposed that effort, saying most of those ballots were probably cast by people who just didn’t want to vote in the presidential elections. The battle was waged in courts for days and ultimately was the issue that the U.S. Supreme Court seized on to stop the Florida recount, citing the lack of statewide standards for judging the validity of a partially punched ballot.

To its credit, the Republican-dominated Florida legislature realized that it was unfair to voters not to examine a ballot before concluding that it shouldn’t count and so after Election 2000 it made mandatory the physical inspection of any “undervote” ballot. But when it came time to carry out the legislative mandate in the Broward County State House race, there was nothing to examine. The results stood.

So why weren’t the voting intentions of 134 citizens recorded? There are two theories. The first, laughably put forward by ES&S officials in an election in which there was no other issue on the ballot, was that those voters simply weren’t interested in casting a ballot in that race. Later, they suggested a different reason: The voters had failed to press the red “vote” button, per instructions, after reviewing their choices, and election officials at the polls, who are instructed to press the button before clearing the machine for the next voter, failed to do so. So as in Election 2000, the failure of a vote to be recorded was laid to voter error or, possibly, to election staff error.

Not surprisingly, machine error is not suggested, either by ES&S, which would have no interest in suggesting its system might fail occasionally, or by elections officials, who had just spent $17 million to buy the machines. Yet as we all know, computers sometimes don’t do exactly what we ask them to do, and if there was one thing I came away with from the Herald’s review of presidential ballots in Florida in 2000 it was this: Voters don’t go to the polls, in a presidential race or any other, with the intention of not voting. While many of the punch card ballots bore no signs of a presidential preference, I am convinced that was the result of machines that hadn’t been properly maintained.

There’s a push now in Florida, and in many others states, as well as in Congress, to require that touchscreen voting machines provide a paper printout stating the preferences of a voter. The printout would become the ultimate check of the voter’s preferences. Nevada and California require such printouts now. Other states should.

There is another issue about touchscreen voting machines that is more difficult to resolve, however, and the debate over it is an important one for journalists to follow. Just how secure are the machines themselves from tampering?

Much of the attention on this issue has involved machines manufactured by Diebold, Inc. of North Canton, Ohio. Maryland and Georgia have chosen Diebold machines as their balloting system statewide, and other states are using them in some jurisdictions. Last July, university security experts accused Diebold of not having enough security safeguards in the software to make sure that hackers, or people with more malevolent motives, could not tamper with the results.

Diebold immediately countered that the software the researchers had used to conduct their tests was first generation and that Diebold had fixed the problems. But in late January, a group of security experts hired by the Maryland legislature issued a report that found that Diebold software still didn’t do enough to prevent outsiders from tampering with the machines. They said machines could be reprogrammed fairly easily to make a vote for one candidate count for another.

The researchers suggested some temporary fixes that would increase the machines’ security in time for Maryland’s March primary and the November general election—something Diebold saw as an endorsement of its system. Diebold noted that if there was no tampering the tests showed the machines accurately tabulated votes. Hurrah.

Reporting on Voting

But the fact that we are about to head into a new election, with the likelihood of another close presidential race, with balloting systems that either are known to be flawed (punch cards in 22 states) or are largely untested and likely to be flawed (touchscreens) is an unnerving prospect, at best.

Is there anything that can be done now? Probably not. The hopeful sign is that the balloting in the few primaries held as I write this have had few problems. Dan Seligson, the editor of electionline.org, the Web site of the Election Reform Information Project, says he’s gotten few reports of serious difficulty. Missouri’s voting has at this writing been the biggest test so far and that went smoothly, though, as Seligson noted, it also wasn’t close.

And there’s another hopeful sign. News media interest in the actual process of balloting seems to be high. Seligson says reporters are talking to him on a regular basis about balloting issues. “There seems to be a much greater awareness” of the potential for problems. “They are hungry for information.”

Let’s hope so. Voters who are informed by an aggressive and interested news media will be forewarned about possible problems and make certain they don’t occur. Thinking back on that call I got about the flurry of paper in the Miami-Dade County ballot counting room, I always will wonder if there was something I as a journalist could have done that would have changed the way ballots were counted in the 2000 election. Maybe not.

But with so much on the line, every one of us should make certain that the basic right to vote, and to have our votes counted, is not thwarted because of simple errors that could have been corrected. That means paying attention not just to whom people are voting for, but also the kinds of machines they are voting on, the procedures by which those votes are counted, and the safeguards in place to make sure the results of close contests can be verified.

To do otherwise would, in fact, be crazy.

Mark Seibel, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, directed The Miami Herald’s review of disputed Florida ballots after the 2000 presidential election. He is managing editor/international in Knight Ridder’s Washington bureau.