Voyages of Discovery Into New Media

At the crossroad of old journalism and new media, digital news entrepreneurs lead us on voyages of discovery into new media. From MinnPost to MediaStorm, these entities are using visual media, interactivity and social media to watchdog government abuse and the justice system, identify environmental dangers, and tell enduring stories. In doing so, they illuminate possibilities.

Brian Storm is the president of MediaStorm, a production studio located in Brooklyn, New York, which publishes multimedia social documentary projects at www.mediastorm.org and produces them for other news organizations. In an interview I did with Brian on December 30, 2008, he spoke about how he envisions the future of long-form, multimedia journalism from the perspective of its creation, distribution and economic viability. An edited version of our conversation follows.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Brian Storm’s University of Missouri School of Journalism commencement speech »Melissa Ludtke: In a commencement speech that you gave in December to graduates of the University of Missouri School of Journalism, you let them know that you are optimistic and passionate about journalism. Can you describe where your optimism comes from at a time when we hear so much about the enormous challenges facing journalism and this despair being expressed by so many journalists?

Brian Storm: The journalism industry is not in despair, it’s simply going through a redefinition. I feel like we’re living in such an epic moment, a transformational moment. Think about the big stories happening right now: climate change, new president, and an economy that is totally falling apart, and as journalists, these are big stories. It’s a great journalistic moment to be in this business. The big opportunity is that the tools are so powerful that anyone can create high production value content and distribute it globally. I EDITOR'S NOTE

Before he founded MediaStorm, Brian Storm was vice president of news, multimedia and assignment services at Corbis, a digital media agency, and director of multimedia at MSNBC.com.don’t need to own a printing press or a television station, but I can be on television through new distribution devices like Apple TV or TiVo. It’s an absolutely revolutionary moment, and I feel incredibly empowered as a journalist. As a storyteller, I feel empowered to do the best work of my career right now, even though I don’t have the big mainstream media infrastructure sitting underneath me that I used to have. Now I can do the kind of stories that I’ve always wanted to do without any limitations.

Ludtke: Let’s talk about the other part of the equation—the passion for journalism. There is so much tension now, with journalists trying to find a way to earn a decent living using new media tools and distribution. Where do you see the passion fitting into that part of the equation?

Storm: I certainly can understand why journalists at big media companies are depressed. Their passion for journalism I don’t think has changed at all. It’s the business environment that is creating this chaos. Everyone is being asked to do everything and nobody is being allowed to do in-depth quality journalism.

Ludtke: Where do you see the passion that you bring to journalism emerging? You’ve talked about the difficulties and challenges that a lot of journalists are facing today. How do you see passion being imbued into this?

Storm was also interviewed in the Spring 2010 issue of Nieman Reports.Storm: For years I’ve been saying it’s time for us to take journalism back. To take it out of the business development role and back into the world of why we got into journalism in the first place. We have to remember back to the time when we decided, “I want to be a journalist.” Why did we want to be a journalist? Did we wake up one day and say, “I want to make a pile of money?” I don’t think any of us did that. That’s not what drives us. We’re curious and want to learn about the world. It’s an incredible gift to enter into someone’s life and tell their story. What makes me passionate is that I feel now, even though the fiscal environment is way out of whack, the ability to do stories at the level that I always aspire to do them is here; it’s right in front of us in such a profound way right now. With the ease of distribution and the powerful new production tools, journalists can practice their craft with independence.

Ludtke: You touched on this, but let me explore it with you a little bit more. In many newsrooms now, reporters are being expected to use a variety of new media tools. They’re being trained in sort of a helter-skelter way to tell stories across several platforms on the Web, and also for many, still in print. Having this expectation of producing this kind of quality reporting with video, audio and print on stories seems very tough for them to meet. Yet at MediaStorm, your approach is very different. Can you describe how you see multimedia storytelling working best to produce high-quality journalism?

Storm: You sneaked into your question the word “quality,” so I’d have to disagree with you on that. You said newsrooms are asking reporters and journalists to do everything, but the word ‘quality’ doesn’t come into that conversation. The phrase that comes into that conversation is “do more with less.” It’s not a journalistic decision; it’s not a decision being driven around telling better stories. It’s the decision being driven by creating stories in ways that are more economical, more fiscally responsible.

Ludtke: By having one person do more.

Storm: Yes. I don’t know one person operating at a high level who is an independent one-man band who is telling the kind of stories that you could tell in a collaborative environment. There’s just no way. In every project we do, several people collaborate to make that story happen: the designer, the producer, the executive producer, and the journalist who covered the story in the first place. What we’re trying to create are universal stories that are not perishable. That’s the core element of our strategy. We publish a story in 2006, and a certain amount of people see it when it comes out, and the blogosphere takes over and they promote it like crazy; it’s all viral, all word of mouth. It doesn’t matter if you watch this story in 2006 or 2009. It’s still relevant and still a powerful story. Those are the kinds of stories that we’re looking for—projects that are not perishable but will endure for years. That’s a different editorial focus than a daily product, and it takes a team of experts with a variety of skills to pull it off at a high level.

Ludtke: Your training originally came in visual journalism, but can you talk a bit about how audio is best employed as a storytelling tool as part of visual media?

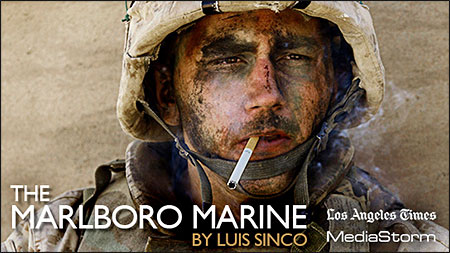

Storm: For me, audio has always been the extra element that helps make a story work. One of my favorite examples of this is a project about “The Marlboro Marine” from Iraq. His image became an absolute icon. Everyone in the world saw it; everyone perceived it as the macho, badass American. The reality is that that’s exactly wrong. His life is an example of incredible posttraumatic stress disorder, which about 30 percent of our soldiers coming home are suffering from. Having [the Marine] James Blake Miller’s words with the pictures allows him to tell you the reality of the situation. It gives a context, and that makes the visual images much more powerful. In this case, we did an interview with the photographer, Luis Sinco; this gives transparency to our stories. I want people to understand the kind of passion that these photographers have. The way we present this on our site, he is the backstory, but the engagement of the story and the way in which he interacts with it are compelling elements. We need to create more transparency in the way we do photojournalism so people have a better understanding of it.

RELATED WEB LINK

"The Marlboro Marine"

- Luis SincoLudtke: Storytelling is something that humans have done since the beginning of recorded time, on cave walls, now in cyberspace. You’ve observed that the new media revolution that we’re going through is not about some reinvention of storytelling or the journalistic creed. Ethical and accurate information will still rule. Instead, you talk about how much it is about the access people have to the powerful tools to produce and distribute the information through the interconnected global Web. Can you talk about how this ease of access is remaking the process by which news and information is being gathered and absorbed?

Storm: When everyone has access, that is disruptive and causes chaos. Access is the territory that journalists used to own and now they look at what is happening with the crowd. The crowd has access to these great digital cameras, to this incredible powerful publishing tool called the Web, and they have expanded the conversation. They have access to distribution that we, as professional journalists, have. This doesn’t make me fearful; it makes me excited. That’s democracy—to have more people, more input, and more access to different perspectives.

We, as journalists, also have to elevate our game. We can’t keep doing things the way we’ve always been doing them. We have to get better as journalists. From my perspective, this actually helps long-form in-depth journalism since the crowd is less likely to go that direction. In fact, they’re taking some of the burden off of us in producing and discovering the things that waste our time. For me, the larger question is why we are wasting our time and skills covering stories that the crowd is all over. Why are we, as professional journalists, allocating our resources for such daily, perishable stories? We should be allocating them for things that are in-depth, investigative and require the kind of expertise and professionalism that we have. We need to take a deep breath and remember all the things that we used to do, then reconsider given the new landscape and decide what is going to give us the most value over time. What is the role that we need to play? I don’t believe that is day-to-day, perishable content. I think we need to be more in-depth, more investigative, and more robust in what we do. I know that over time, that will actually pay off. That has proven itself time and time again for us at MediaStorm.

Ludtke: You’ve talked a lot about a new breed of journalistic entrepreneurs. What you’re doing at MediaStorm is a good example of how to be entrepreneurial in the new media era. Can you describe the key ingredients an individual needs to pair their interest in journalism with an entrepreneurial business model that will provide a foundation from which they can do it?

RELATED ARTICLE

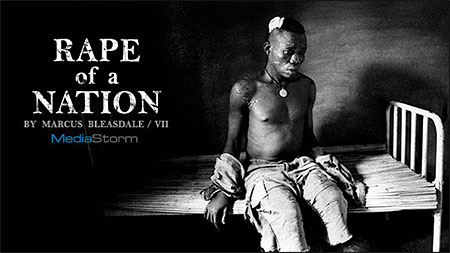

View a Nieman Reports photo essay by Marcus Bleasdale in the Fall 2004 issue »Storm: That’s the core question. How do we practice the craft and make a living? For me, the element of entrepreneurism has to be there. There used to be the separation between church and state. I’m a journalist, and I’m not going to think about page views or advertising or business models; it’s not my job. My job is to tell the story. That era is coming quickly to an end. We’re all well aware of this. The legacy business model needs to be completely rewritten. The way in which media companies used to make money has changed, in fact, the way in which every company used to make money has changed. It’s a revolutionary moment. We need to rewrite how we communicate with each other. That’s a pretty big deal, but I’m excited because in disruption there’s opportunity. You have to look at the landscape, take what you care about, build on it, and then reinvent the other parts. That’s why I think it’s really important that the next generation of journalists have to be more entrepreneurial. I don’t just mean that in a business sense; I also mean it in an outreach sense. Like how do we get our stories out there? How do we get the right people to get to the stories that we care about? That’s entrepreneurial thinking. It’s not just how do we go make money, it’s also, how do we connect with the right people, how do we get involved with the right groups who can advocate for change? That’s a big leap. At MediaStorm, we’re focused on advocacy, not just information. We don’t want to just create awareness with our stories, we want to create action.

Ludtke: More the need to find the right people, to find the agents of change.

Storm: Exactly. The story we’ve done with photographer Marcus Bleasdale is about the Congo. The people who care about what’s happening there will find it, and they are already helping, and this is brand new. Ten years ago, this was impossible to do. Today, with a click of a mouse, it’s off; one person can quickly spread this story, and it’s not just one network. It’s powerful. It’s unbelievable, and it’s driving awareness.

RELATED WEB LINK

"Rape of a Nation"

- Marcus BleasdaleLudtke: You use the phrase “surge of connectivity” to describe what you see as the greatest hope for restoring quality journalism. At MediaStorm you don’t publish on any set schedule, nor do you advertise the stories you publish, at least in traditional ways. Yet many of your long-form multimedia pieces find a global audience. Talk more about how this happens, giving an example of one of your projects growing its audience.

RELATED WEB LINK

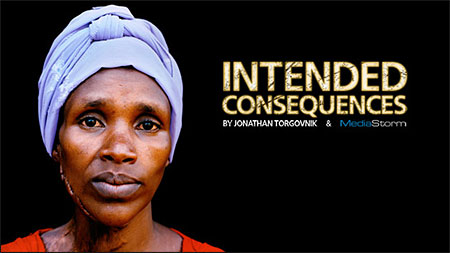

“Intended Consequences”

- Jonathan TorgovnikStorm: For the most recent project we published on Rwanda, I sent an e-mail out to 11,000 people who signed up to receive our newsletter. The e-mail goes out, and there’s a surge in traffic. Immediately, people start clicking the link, and over the course of several days traffic continually climbs, because a lot of those 11,000 people are forwarding that e-mail to their friends. And what is more powerful than you sending me an e-mail saying, “Brian, you have to look at this project. You’ve got to find the time to look at this thing”? It’s the most powerful word of mouth marketing that can possibly happen. Your friends are trusted sources. They’re helping to screen a massive amount of information that you have access to, helping to filter in the good stuff, which again is why I really believe quality is the key. If you just push out a bunch of drivel, no one is ever going to forward it to a friend. Over time, there’s no payback on that. After the e-mail surge happens, then people start blog posting it; that is another really powerful thing, because we have people from 135 countries who come to our site every month. That still just baffles me. People from all over the world come to our little Web site to watch stories, and the way they find it is e-mail, blog posts, and Tweets. Ten years ago, all of these ways for people to spread information didn’t exist.

Ludtke: You’ve said your RSS feed drives 35 percent of your traffic to the Web site. And now you are saying Twitter accounts for a large amount of it, too.

Storm: Yes, Twitter went from nowhere, not even on our radar four months ago, and it is now number 11 in driving traffic to our Web site, which I just think is remarkable. Facebook is number seven.

Ludtke: What’s number one?

Storm: Google. I think you would be hard pressed to find anybody who didn’t respond to Google as their number one traffic driver.

Ludtke: Twitter is now number 11.

Storm: It’s a remarkable thing to watch that grow. It just proved to me that people care. It’s so ironic. Ten years ago, I remember sitting in a newsroom and scratching my head, saying, “How do we get people to care about AIDS in Africa? How do we reach people with this story?” I remember everyone in the newsroom saying, “The audience is apathetic; they don’t care.” I felt that was wrong. They do care; of course, they care. They just need to have access to this stuff.

The irony now is that the apathy we’re seeing is actually inside of the newsroom. The audience is totally energized, totally connected, and totally spreading around these powerful stories. But because of the crisis that we’re going through, news organizations don’t have the resources to do the kind of stories that I’m describing. People are asked to do less with more and not given the time. Time is the greatest luxury in journalism. It’s why we don’t publish on a deadline. We publish when we feel a project is ready. All of these things connect to each other and in really interesting ways to passion. What an exciting time to be practicing journalism!

Ludtke: Many of the stories on MediaStorm are lengthy, some more than 20 minutes. At a time when it’s said that people’s attention spans are shrinking as they dash around from link to link, never stopping very long at any one site, why are you convinced that doing long-form journalism on the Web is viable as a business strategy?

Storm: The data tells me it’s true. This is one of the things that used to drive me crazy when I was at MSNBC. Microsoft, its half owner, is a very data-driven, metric-centric culture. They look at numbers, so that is built into my DNA now. So that’s what I do: look at our numbers on the dashboard. I can see how our publication is evolving—time spent on the site, where traffic is coming from, whose blog posts, who’s spreading it for us. I have visibility in a way that is totally profound. I know so much about how our publication is and is not working, because the data are right in front of me. I think data can also be evil. A lot of people run around and say, “We need page views, we’ve just got to have video ….” Sometimes they don’t interpret the data correctly. Sometimes data can be used in a way that is not good.

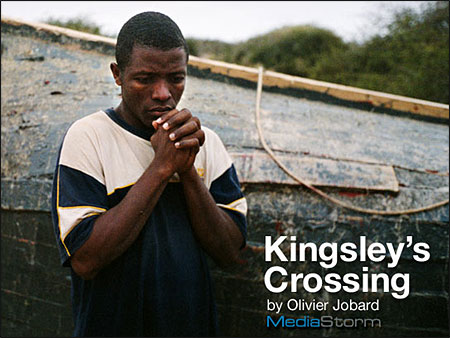

For me, though, it’s wonderful to have the ability to see how many people are watching our 21-minute video about a young African man’s journey to get to Europe with the help of smugglers. What percentage do you think watch 21 minutes from start to end on our site? The answer is 65 percent. That is an astonishingly high completion rate on the Web. When you think about it, it goes back to quality. The only reason they’re watching it is because it’s just a great story. We develop the character in a way that you start to care for him, you see yourself in the character, and you’re hooked. You have to know: does he make it? And then, once he makes it, you say, “Holy smokes, he’s thinking about going back for real.” That is what we’re looking for, that universal, robust, in-depth coverage of an issue that people can relate to—immigration. A lot of people migrate; a lot of people leave their families in search of “a better life.” In Kingsley’s case, it’s still up for discussion whether his life is better or not.

RELATED WEB LINK

"Kingsley's Crossing"

- Olivier JobardLudtke: We’re going to link to your Web site and these projects you’ve mentioned so that people can see some of these stories themselves. Can you describe some of the common threads that you see weaving together the various stories MediaStorm.org has published?

Storm: That’s a really hard question, because I often get asked to describe what MediaStorm is, and it’s going to sound weird, but one of my goals is for people not to be able to describe it. When people come to the homepage, it’s not really clear right away what it is. A lot of news sites look exactly the same; they all have the identical template, design and aesthetic quality. I want people to come into our site and say, “What? I don’t understand.” They have to explore, and that’s the idea behind the promos on the homepage; touch a project and see a little piece of the story. Every story is different on our site; we don’t have a specific editorial focus. There are not certain topics that we care more about than others. What I want people to do is try to start explaining the site, but then they get frustrated and say, “You should just go see it. It’s really good. It’s worth seeing.” Those are the words I’m hopeful people will use. Those three sentences. “It’s really good, and it’s worth your time. Go see it.” I think everyone will look at stories and take away different things from them. There is no quick slogan. We’ve been called “the new Life magazine,” or “the Life magazine of the Internet.” That is a pretty awesome description, and I appreciate that people see it that way. There is a certain element of that that is accurate in terms of our aspirations. We’re trying to do stories that show life and help people better understand the complex world that we’re in. It is complex. I think the way in which we approach these stories helps to make those ideas more understandable and more accessible.