Writing the Book

How does a journalist make the journey to author? A variety of paths and potential pitfalls are here for you to learn from. Authors of memoirs, novels and nonfiction narratives write frankly about the ups and downs. These days the topic of books can’t be discussed without mentioning online platforms and self-publishing so you’ll also hear from the individuals behind The Atavist and Byliner as well as an author who brought his book back from the dead via print-on-demand. If you have a publishing (horror or success) story you’d like to share, please drop us a line at nreditor@harvard.edu.

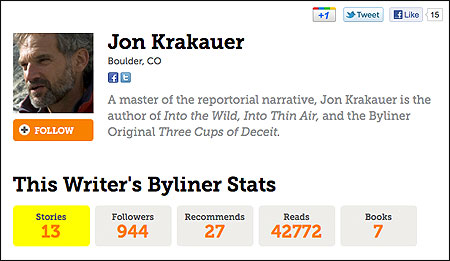

Byliner.com collects and shares information about its authors’ social media connections.

How many words do I have? It's a question I'm accustomed to asking whenever I write a story. Sometimes I ask it of myself, more often of my editor. Before I started writing this piece, I asked the editor of this magazine for a length.

"You've got 1,000 words," she replied.

RELATED ARTICLE

“The Writing Life: Examined in a Digital Minibook”

- E-Book Excerpt by Ann Patchett That's an arbitrary word count, of course, since I could tell the story of our eight-month-old digital publishing effort in fewer words. Or I could tell it in more. With my words destined for Nieman Reports's print pages—and for its website—it's natural for the editor to think about how many words she wants and what visuals might accompany them. This is a sensible approach and until recently was how publishing worked, whether in a magazine or a book. Editors assigned story lengths, then slashed or stretched what got delivered to a workable word count, even when that count might not serve the story well.

Over the years, I've often been the one doing such slashing and stretching. It's never fun. Some stories escaped unscathed, but most suffered—and their writers suffered—simply because a few magazine ads went unsold or the marketing department felt a fatter spine would sell more copies in bookstores. Oh, we waxed poetic about "letting the story find its natural length." But deep down we knew it wasn't possible. A story that needed 10,000, 20,000 or even 30,000 words to be properly told inevitably fell into publishing's dead zone. This represented the vast wasteland of impossible-to-place stories that were longer than magazine space permitted and shorter than a book was thought to be.

Swift Publication

In January 2009, a year before the iPad was launched and two years before Amazon introduced Kindle Singles, I was chatting with some writers and editors about an idea for a company that would bring stories that fell into that dead zone to life. Our idea was to create a new way for writers to be able to tell stories at what had always been considered a financially awkward length. Such articles—at this longer length they were likely to be told as narrative accounts—would be reported and written swiftly, not unlike a magazine piece. We'd sell them on digital platforms as e-books.

Back then I scribbled this note about our concept: Essentially, we're creating a royalty system for long magazine pieces, and the writer benefits from the first copy sold. It's a nice change of pace for established book writers, looking to test-drive an idea or to clean their palate after a multi-year project. For established magazine writers, they're actually invested in their pieces.

As always, word count would matter, but not in an overly limiting way for writers. These swiftly conceived and completed books would be done at a length—fewer than 30,000 words—that would make them readable in two hours or less. (The average American reads 250 words per minute.) We wanted to give writers the opportunity to draw out the complexities of a story and get it in front of potential readers while the event or action or news is relatively current. Our strategy would liberate them from the pre-determined schedules of traditional book and magazine publishing.

At least, this was our theory, tested with our first Byliner Original by Jon Krakauer. He was troubled by certain details in Greg Mortenson's bestselling book, "Three Cups of Tea" and had heard unsettling allegations about his charity work. He knew there was an important story to be told—which required depth and length, but the investigative piece he wrote was 20,000 words long. At that length, it didn't work as either a conventional magazine piece or a book. There were timing challenges with publishing it, too: Krakauer wanted to release his story when a "60 Minutes" report on Mortenson would be aired in mid-April. Yet he wanted also to be able to keep reporting—adding details to his investigative essay, as he unearthed them—up until its release.

Happily, we discovered he could do this. Byliner published "Three Cups of Deceit" at 22,000 words, some of which were written, edited, checked up to an hour before publication and based on reporting he'd finished that day. We released Krakauer's e-book on our website immediately after "60 Minutes" aired its own exposé, in which Krakauer was featured. As our website's initial offering, his e-book was made available free of charge during the first 72 hours when some 70,000 readers downloaded the PDF version. When his e-book went on sale in Amazon's Kindle Singles store—neither Apple's Quick Reads nor Barnes & Noble's shorts digital storefront were open yet—it quickly became the top selling e-book; it has sold steadily ever since at $2.99. In subsequent months, Byliner has sold more 100,000 e-books, including those written by bestselling authors such as Ann Patchett, Mark Bittman, and William T. Vollmann.

Aggregating Audience

The writing and publishing of e-books tells only half of Byliner's story. With our (relatively) long gestation period, we spent an inordinate amount of time thinking about how our site's e-books would be discovered and how writers would acquire and grow their fan bases. We knew we didn't want to rely on the customary book-publishing model—get the book into stores, send the author out to talk it up, and hope for good reviews so it can gather an audience. We wanted to upend that scenario by aggregating an audience via an author's social network; in this way, we could commission an original e-book and publish it (essentially presold) into that targeted fan base.

To do this, we worked to construct a discovery platform to complement our publishing efforts. Byliner.com utilizes well-known social media techniques, such as a Twitter-like system alert so that readers don't miss the publication of an e-book by their favorite writers, as well as a Pandora-like recommendation system that helps readers discover new authors. Importantly, it also enables authors to leverage their back catalogs of narrative pieces so they can better market their latest e-book.

Even though our pieces are long—at least when compared with newspaper or magazine pieces—we still keep an eye on word count at Byliner. For example, we know that the average word count of the Byliner Originals we've published is 23,765 per e-book. If a fan of Michael Lewis wants to check out his long-form stories, Byliner can point him to stories he's written adding up to 428,465 words. In all, readers can choose among more than 60 million words that we've collected, organized, published or spotlighted. Our focus is on providing writers with the space that works well to tell long-form contemporary stories and the platform from which to sell them. Yet, we also know that Byliner is working as a go-to place for readers looking for vivid storytelling that displays depth, breadth and complexity—without all of those hundreds of pages to turn.

John Tayman is founder and chief executive officer of Byliner.