It’s no secret that the media industry—in the U.S., in Central Europe, and around the world—finds itself in deep trouble these days, struggling to stay afloat amidst all the turmoil: violence and political attacks, wavering loyalty among some audiences, and layoffs and crumbling business models aplenty. And yet, journalism, the product itself—the words, the pictures, the sounds—is in many cases thriving.

Revenue models also are a concern in Central Europe. But on top of that are the challenges surrounding the “oligarchization” of the media and repressive leaders. Still, independent outlets press on, as Lenka Kabrhelova, a journalist in the Czech Republic, reports. It’s a scary time for journalism—but it’s also an exhilarating one.

It is fair to say that the housing beat has not traditionally been considered a plum assignment among reporters. In fact, many media outlets do not have a team dedicated to housing issues—except for real estate reporters, who typically focus on the market for buying or selling a home. While the collapse of the housing bubble dominated headlines a decade ago, stories about foreclosures faded as the economy recovered and construction of luxury condominiums resumed, particularly in cities where many journalists work.

But the cranes hovering over the skyline overshadowed a different storyline that was developing, pushing housing back onto the front page.

Related Reading

“From Covering the Housing Crisis to Living It”

by Susan Stellin

During the past couple of years, housing affordability has increasingly been recognized as a crisis affecting communities throughout the United States. From high-tech hubs like Seattle and San Francisco to Midwestern markets like Chicago and Detroit, people are getting priced out of their homes. Stories about evictions and rents that are out of reach now profile people earning a wide range of incomes, and housing insecurity is more broadly understood as impacting those forced to move in with friends or relatives as well as individuals sleeping on the street.

“The issue of housing affordability has moved up the income level,” says Christopher Herbert, managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. “Suddenly it’s not just a problem for the poor. It’s a problem for the middle class, too.”

News organizations have responded by tackling topics that both contribute to and result from the growing affordability problem, including corruption and fraud among developers of low-income housing, unfair property tax assessments, discrimination, foreclosure auctions, homelessness, and illegal or unethical evictions. Investigative reporters are digging into data, filing FOIA requests, and knocking on doors to find residents willing to speak on the record, producing work that has prompted policy changes in some cities.

It is fair to say that the housing beat has not traditionally been considered a plum assignment among reporters

Herbert identifies two options he believes warrant more media scrutiny: increased housing assistance for lower-income households and more development of high-density housing, both policies he acknowledges are controversial.

Another hurdle for journalists is understanding and explaining the intricacies of a complicated market, similar to analyzing how inflated housing prices contributed to the financial collapse. “It is hard to get at the truth when you have such a large complex system,” Herbert says.

Laura Sullivan, an investigative reporter for NPR and Frontline, took on the challenge of explaining that complexity for the film “Poverty, Politics, and Profit,” which examined how two key federal programs fail to meet the need for affordable housing in the U.S. Working with producer Rick Young and co-producers Emma Schwartz and Fritz Kramer, Sullivan followed three women attempting to use Section 8 vouchers to find a place to live in Dallas. The vouchers cover the difference between what renters can afford to pay and the monthly rent, but only one in four people in need of assistance get them—and many landlords won’t accept them.

Sullivan sensitively explores the fraught racial and class divide that underlies some resistance to this program, interviewing one stay-at-home mom, Nicole Humphrey, who explains why she does not want voucher holders as neighbors. “The lifestyle I feel like that goes with Section 8 is usually working single moms or people who are struggling to keep their heads above water,” Humphrey says. “And it's not—I feel so bad saying that. It's just not people who are the same class as us.”

Asked what it was like to have that conversation on camera, Sullivan says, “I was grateful to her for explaining the problem and being honest about it. I think it was eye-opening because she was expressing what other people feel and the more you can air that and get it out in the open the better.”

The film also explores the history of the Fair Housing Act and investigates why the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit costs the U.S. Treasury more annually (about $8 billion) with fewer units getting built. Sullivan interviews developers who pleaded guilty to corruption related to this program, but also addresses the fundamental challenge of building housing for workers earning less than $20,000 a year. “You can’t work at a fast food restaurant and live in America, period,” Sullivan says. “There was a time when you could.”

In order to get a more well-off audience to stick with a complex narrative—rather than tuning out due to sympathy fatigue—Sullivan thinks it’s important to build in what she called “an accountability piece. If you go in and just describe how difficult it is to either find housing or afford housing you lose a lot of people. It seems like one more sad, impossible thing to fix.”

Holding powerful people accountable was also a key theme in Jason Grotto’s four-part series, “The Tax Divide,” published by the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica Illinois. Based on a two-year investigation that involved analyzing more than 100 million computer records, the series documented the unfair property tax assessment system in Cook County, Illinois, which overvalued the homes of poor residents and undervalued higher-priced homes.

“When I first went to my boss, he said, ‘So we’re going to basically say people aren’t paying enough in property taxes?’” Grotto recalls, recognizing that the paper’s readers were more likely to live in undervalued homes. “I said the issue isn’t how much do we pay in property taxes—the issue is how is that burden distributed among people and is it fair.”

Grotto had years of experience doing data analysis, but he ended up partnering with Christopher Berry, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy—even co-teaching a graduate-level class to students who helped with research for part of the series. “I’m a firm believer that collaboration is key,” Grotto says. “The idea that we’re going to do it all ourselves is sort of an old way of thinking.”

The series revealed serious problems with Cook County’s model for determining property tax assessments, as well as issues with the appeals process that made the system even more unfair. Grotto anticipated some pushback from the assessor’s office—but not the press conference that was held to attack his work. Ultimately, an independent study commissioned by Cook County corroborated Grotto’s findings, and assessor Joseph Berrios lost his bid for re-election earlier this year.

Although the political and statistical threads might’ve put off some readers, the series included an interactive tool so local residents could find out if homes in their area were over- or under-valued, as well as multimedia clips explaining things like how property taxes are calculated, and videos featuring homeowners struggling to pay excessive bills.

“Housing stories are tough,” Grotto says. “There are a lot of technical aspects and a lot of financial details and it takes time to dig through that stuff. At the same time, there are few things that are more important in individuals’ lives than their homes so I think there’s a lot of great storytelling to be done.”

One big hurdle for journalists is understanding and explaining the intricacies of a complicated market

For The New York Times series “Unsheltered”—about tenants in rent-regulated apartments being pushed out of their homes by aggressive landlords—Kim Barker says finding people willing to share their stories took a lot of research, negotiation, and time: “I didn’t want to start with a worst-case scenario. You want to write about how the system handles an average case and to find an average case you have to pick through a lot of data.”

Barker and her colleagues were able to get five years of New York City housing court data—more than a million cases—but those records did not indicate how each case was resolved so the team had to build a spreadsheet themselves.

The focus of the series was how weakened housing laws and a lack of oversight have allowed landlords (often, corporations or investors) to harass tenants into leaving rent-regulated apartments. Some of those tactics include noisy, off-hours construction, making dubious renovation claims in order to push apartments into the free market, or filing eviction suits based on fraudulent accusations like lease violations. But out of fear of reprisals or landing on a tenant blacklist, renters can be reluctant to discuss their cases on the record.

“You’re talking about having somebody talk publicly about their landlord which is a really difficult thing to do,” Barker said. “I’m very honest about what will happen—I say your name is going to be out there. I don’t let people approve or change their quotes, but I go through the parts that involve them. I do that with landlords, too. They need to know exactly what I’m going to say about them because I want to know if I’m wrong.”

To illustrate the loss of rent-regulated apartments in New York City, the series included a graphic of a building in Upper Manhattan that had 66 regulated units in 1996, 19 of which were free-market apartments by 2018—renting for an average of $3,875 a month.

Some readers posted comments suggesting that people who can’t afford New York City should move elsewhere, pointing out that “Trying to get through housing court to evict a deadbeat tenant in a timely manner is virtually impossible,” and asking, “Where's the story of empty nesters with vacation homes in Florida maintaining their rent controlled pied et Terre [sic] so they can come see Hamilton on Broadway?”

“We were shocked by some of the comments,” Barker says. “My editor was just like, ‘When did people become so mean?’”

As with many topics in the current political climate, stories about affordable housing can prompt a range of reactions—some thoughtful, some vitriolic—heightening journalists’ ethical responsibility to consider who they choose to profile and anticipate how those sources will be viewed. Another New York Times article, about the demolition of a public housing complex in Chicago, featured a woman with 13 children, a fact that for some commenters overshadowed almost every other aspect of the story.

Holding powerful people accountable was a key theme in “The Tax Divide”

That response points to an issue that frequently comes up in comment sections and social media posts: how much individuals are responsible for their own housing woes—say, because they bought new furniture instead of saving that money for a rainy day.

“A lot of people attribute the problem to personal responsibility rather than the systemic challenges that exist,” says Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National LowIncome Housing Coalition, which is trying to shift public opinion about affordable housing and the hurdles low-wage workers face. “Often you see a lot of outright racist or very racially tinged comments that get at our very complicated racial history.”

Her organization publishes an annual report called Out of Reach, which calculates how many hours someone making minimum wage would have to work in order to afford a two-bedroom home at a fair market rent. This year, that report was searchable by zip code, making it easier for reporters to analyze the data down to the local level.

“Out of Reach this year got 1,100 media stories in its first month of publication, which is the same as we got last year in six months,” Yentel says. She views that as a sign of increased media coverage of the housing crisis, but also a result of providing relevant data to local reporters who may lack the resources to crunch the numbers themselves.

One change she has seen with recent coverage of the housing crisis is more of an effort to explain the roots of the problem: major cuts to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s budget dating back to the Reagan administration, more people entering the rental market because of foreclosures, millennials delaying homeownership due to student debt, and stagnating wages as rents rose.

However, she’d like to see better access to timely housing data, noting that her organization relies on sources that can be years behind what’s happening in local communities, and also more stories that debate solutions. “We put out solutions every chance we get,” Yentel says, expressing frustration with media coverage that doesn’t explore how problems could be fixed. “Sometimes I’ll be on a radio show and we’ll spend 10 minutes talking about the problem and then the segment is over. Change will only happen when we recognize and talk about and educate people about solutions.”

That can be tricky territory for journalists, who may feel ethical guidelines about objectivity mean refraining from weighing in on solutions, or require giving both sides of a debate equal weight. So an article about a proposal to build affordable housing in a higher-income neighborhood would typically include quotes from supporters and opponents, without favoring either group.

But some readers want reporters to include more insight and perspective in their stories, as audiences gravitate toward media outlets that reflect their own views. Others appreciate reporting that offers enough context and expertise for them to make up their own minds about an issue, rather than investing time in an article or segment that feels inconclusive.

It can be difficult for reporters to find, understand, and frame a group of people experiencing something many of us haven’t lived through ourselves

Kriston Capps, who writes about housing, architecture, and politics for The Atlantic site CityLab, covers federal and state housing policy as part of his beat, which has included reporting on HUD’s budget, the impact of lending practices on housing segregation in St. Louis and Jacksonville, and how tax law changes may affect home values in places like Connecticut. “That’s kind of our sweet spot: finding those local stories that have some national relevance,” he says, recognizing that shrinking local media means there are fewer reporters attending meetings where zoning regulations and development proposals get discussed. “Housing is a beat in every place, but not every place can afford to have that beat writer.”

He also focuses on the ways housing overlaps with other social issues, such as education, economic opportunity, and health. For instance, an article about the healthcare provider Kaiser Permanente’s $200 million investment in addressing homelessness and building affordable housing highlighted the intersectional approach some communities are trying to embrace. That multi-faceted view also has implications for how news is reported—moving away from the silos dictated by newspaper sections and supporting teams of reporters with different areas of expertise. But it also requires deciding what topics to prioritize among the many issues housing affects.

Although he believes more reporters are focusing on social equity, particularly since the recession, he hopes real estate coverage evolves into more of a watchdog role, seeking out sources who have access to information and are willing to share it. “There are a lot of public servants who really, really know this stuff and want to talk to reporters about it,” he says.

For the NBC Bay Area series “Kicked Out,” investigative reporter Bigad Shaban and producer Michael Bott filed a public records request to find out which San Francisco landlords had evicted rent-controlled tenants based on a law that allows these evictions if the owner or in some cases a family member plans to move in. “We thought surely the city must require some type of documentation,” Shaban says. “To their credit, the city didn’t try to hide it. Basically they said we don’t check at all.”

So Shaban, Bott, and their team built a database using the eviction records, mapped out efficient routes for their door-to-door reporting, and went to more than 300 homes over six months. They discovered that in one in four cases where they were able to confirm who was living there, the owner or a relative had not moved in.

Ultimately, they got more than 100 responses—some landlords who had indeed moved in, some people who didn’t want to talk, and some tenants who were surprised to find out that they were being overcharged. Although the law allows owners to find a new tenant if their plans change and they don’t occupy the home, they are not allowed to raise the rent to market prices, which have skyrocketed with San Francisco’s technology boom.

The 10-part series includes a map that allows viewers to see if their address was subject to an owner move-in eviction, along with instructions on how to file a rent reduction request. After the series aired, the city tightened up oversight of these types of evictions, and increased the penalty for landlords who abuse the system.

However, Shaban emphasizes, “This was not a story about tenants vs. landlords—this was a story about fraud. We got feedback from some landlords saying thank you for doing this.”

One of the people they interviewed is Angelique Rochelle, a tutor who was paying $1,805 a month for a rent-controlled apartment in San Francisco when she and her three children were evicted so the landlord’s mother could move in. The landlord rented to new higher-paying tenants instead, but Rochelle couldn’t find a large enough apartment she could afford, so her two older children went to live with their father and she and her daughter moved to an apartment in Oakland.

One topic that tends to be particularly fraught for news organizations is how to cover the homeless

In a city where a family making $117,000 a year qualifies as “low income,” these kinds of evictions illustrate how housing insecurity has spread, challenging news organizations to cover the impact on different demographics and the implications for communities where only the wealthy or lucky longtimers can live.

Since television reporters often have to tell a story in a 60-second segment—about a 250-word script—Shaban’s investigative unit was fortunate to have far more time for their series. While online videos tend to run longer, there is still some debate about the attention span of a modern media audience, despite evidence that viewers will watch an entire film on their phones.

Antonia Hylton, a correspondent and producer for “Vice News Tonight” on HBO, did a story last December about a tax foreclosure auction in the Detroit area that has been viewed more than 700,000 times on YouTube. The 11-minute segment chronicles how Judy Kelley lost her home because she couldn’t keep up with the property taxes, simultaneously following Steve and Stevey Hagerman, the investors who paid $3,711 for her home—one of more than 300 they bought through the auction.

It’s a complicated narrative that overlaps with the issue Jason Grotto covered in Chicago. In Hill’s case, she was being taxed on an assessment that was 10 times higher than what she paid for her home. Earning about $2,000 a month as a social worker, she got behind on her tax bill and ended up owing more than $20,000 in back taxes and fees, so the city sold her house in the foreclosure auction.

“We contacted Judy and the Hagermans before we ever knew their stories were going to intertwine,” Hylton says. “It just so happens that as we were reaching out to the Hagermans, they were eyeing her house.”

How to handle that intersection was one of many ethical issues Hylton wrestled with, reaching out to colleagues to get advice on questions like whether it was OK to buy Kelley lunch or pay for her to take an Uber to meet them—given that the Vice crew was taking up hours of her time in the middle of the day.

“What do we do in return to make sure she’s not exploited or financially harmed?” Hylton asks, noting that journalists don’t talk enough about these issues, especially with respect to interviewing sources from backgrounds that are very different from their own.

Hylton is African-American and works with two producers who are also women of color, for an outlet with an audience that can be sensitive to depictions of class and race. That’s why she and her team pushed for an 11-minute segment, so they could present the complexities of the situation Kelley and many other Detroit homeowners faced.

“In a six-minute piece or a two-page article, it’s very hard to go line by line and say here’s what they’re dealing with,” she says, mentioning the challenge of living in an over-policed community or the lack of educational opportunities or jobs. “Often there are a lot of things missing contextually that are really important. The things that viewers get frustrated about and call you out on are the nuances that get lost.”

At the same time, Hylton’s interactions with the Hagermans are not judgmental, giving them the opportunity to explain their business model and challenge what Steve refers to as the stereotype of “the big bad investor.”

Like Hylton, Schultz has had to confront a lot of ethical questions in her reporting, like whether it was OK to buy a meal for a homeless family she profiled

Media coverage of public housing and lower-income homeowners typically focuses on people of color, and Hylton says her race helps her establish trust and build rapport in environments where sources might otherwise be more guarded: “When I walk into a room, often they’re relieved that I look the way I look. There’s an immediate understanding—not that I’m going to be their best friend, but that I see them as a person.”

Another story Hylton worked on, about residents losing their homes in a public housing complex in Cairo, Illinois, is noteworthy for where the key interviews take place. Although viewers see peeling paint and evidence of broken plumbing during a brief tour of one family’s apartment—the result of mismanagement by the local housing authority—Hylton interviews them outside in the grass with children running around a playground in the background. That affords the family the dignity of being able to talk about their situation without being judged for a visual setting beyond their control.

For the foreclosure piece, Hylton and her team were fortunate to be able to spend time in Detroit before they started filming, and she was familiar with the area because her father grew up there. But national news organizations based on the coasts have been criticized for how they’ve covered the rest of the country, sometimes flying in crews that seek out sources who fit the stereotypes they had before they landed.

That can be an issue even when reporting on communities closer to home: how to find, understand, and frame a group of people experiencing something many of us haven’t lived through ourselves.

One topic that tends to be particularly fraught for news organizations is how to cover the homeless, whose ranks have been growing as the housing crisis has spread, especially in cities along the West Coast. In Seattle, officials declared homelessness a state of emergency in 2015 and since then The Seattle Times has expanded its coverage of different facets of this challenge, with support from local foundations, the Seattle Mariners, and Starbucks.

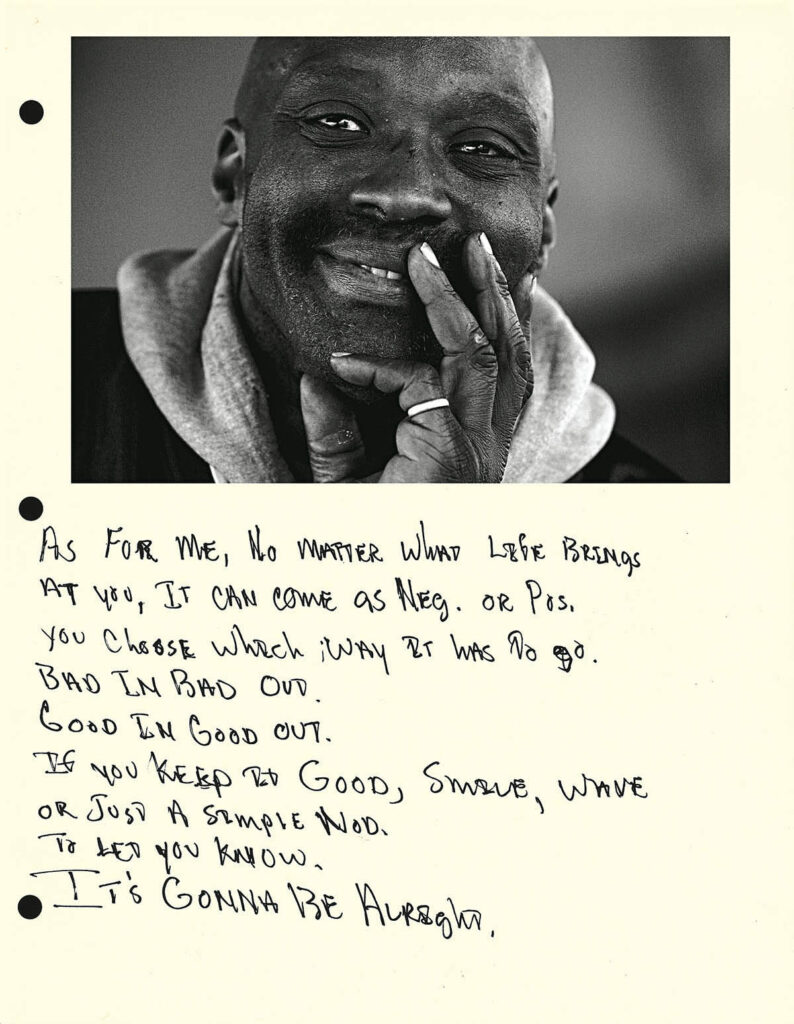

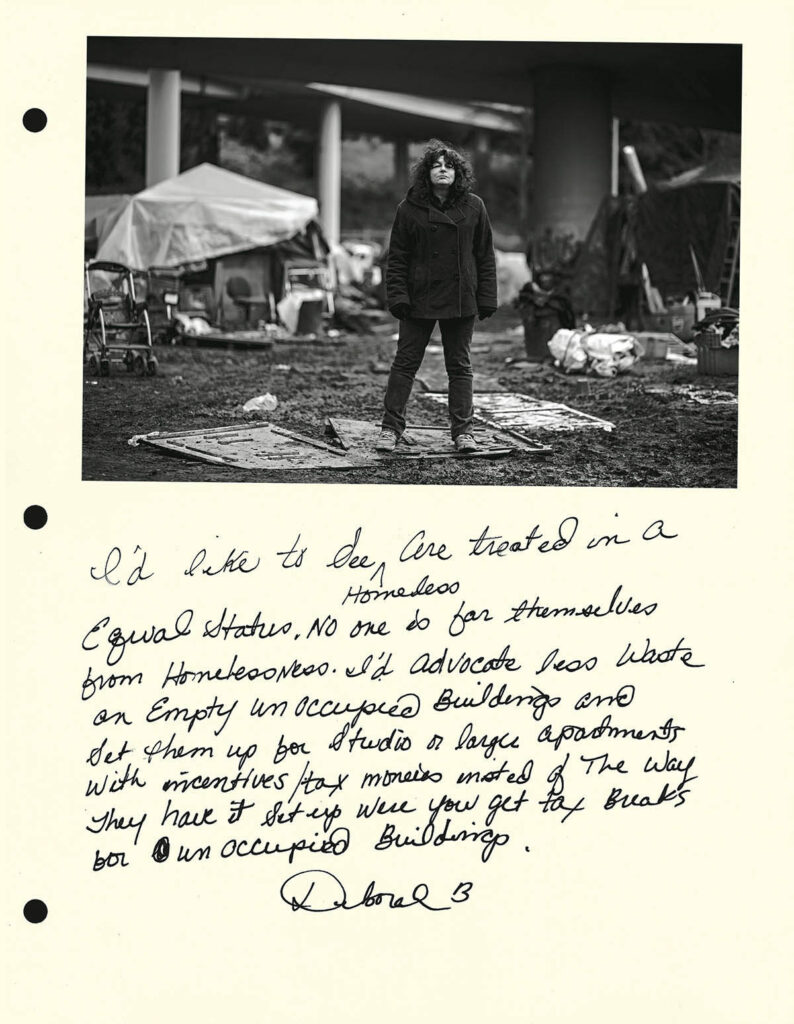

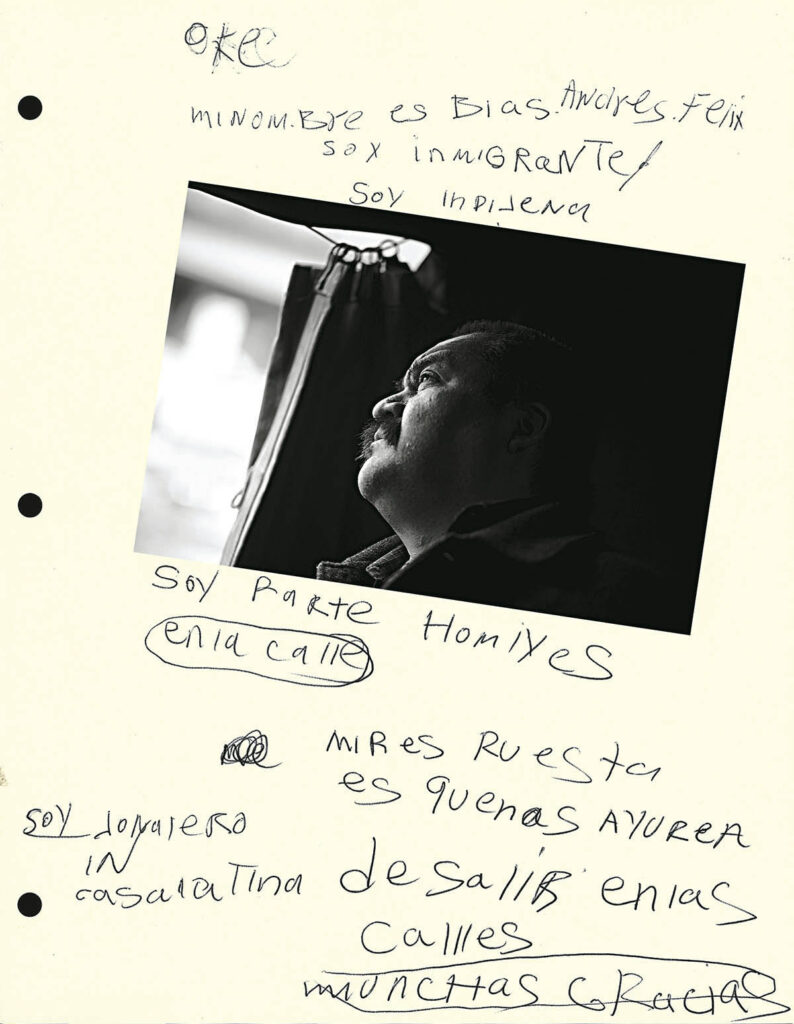

Erika Schultz is a staff photographer who has worked on many projects about housing insecurity, including the series “Portraits of Homelessness” published last year. She and reporter Tyrone Beason visited tent encampments near Pioneer Square, asking residents if they wanted to share their stories.

The series was conceived as a collaboration with participants “to create a portrait that would be a fair representation of themselves,” Schultz says, so she found a battery-operated mobile printer and asked each person how they wanted to be photographed—often letting them choose the pictures they liked. “We gave up some autonomy to allow for better representation,” she says. “The goal was for them to help shape their own narrative.”

Each person was invited to write something on the images she printed, which were scanned and posted online as well as exhibited at the Seattle Public Library. An accompanying article by Beason describes the diverse paths that led the two dozen participants to these camps, which were shut down by the city shortly after their visit.

Like Hylton, Schultz has had to confront a lot of ethical questions in her reporting, like whether it was OK to buy a meal for a homeless family she profiled for a multimedia story called “Jack’s Journey,” or if it would alter the course of the story if she connected them with services. “I would call up my editor pretty regularly and walk through scenarios,” Schultz says. “It’s really challenging to navigate and it’s emotional to navigate as well … especially when there are children involved.” She emphasizes the importance of having detailed conversations with sources up front, then checking in frequently as circumstances evolve. “Especially with minors,” she says, “It’s important to really think about whether we should add last names.”

Photographers are challenged to change how viewers think about housing insecurity, finding imagery that goes beyond foreclosure signs and pictures that reinforce stereotypes

Perhaps more than writers—who at least get hundreds of words to explain a complex topic—photographers are challenged to change how viewers think about housing insecurity, finding imagery that goes beyond foreclosure signs and pictures that reinforce stereotypes about the homeless, particularly as the affordability crisis expands.

“It isn’t just people who are sleeping on streets or camping or living in RVs,” Schultz says. “It’s people who are doubled up or are facing eviction, and people who are living in temporary or emergency housing. It looks a lot of different ways so I think it’s really important to document that.”