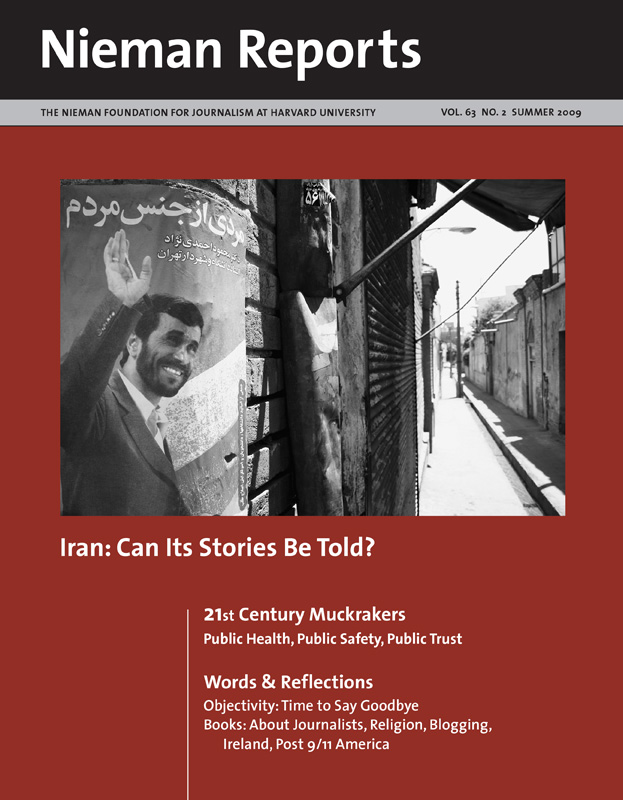

Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?

Journalists — Iranians and Westerners — share their firsthand experiences as they write about the challenges they confront in gathering and distributing news and information about Iran and its people. Their words and images offer a rare blend of insights about journalists’ lives and work in Iran. In the fifth part of our 21st Century Muckrakers series about investigative and watchdog reporting, the focus turns to coverage of issues involving public health, safety and trust. And in Words & Reflections, essays touch on objectivity, religion, blogging, Ireland and post 9/11 America.

A University of Iowa lab analyst scrapes paint from a toy Godzilla. Tests sponsored by the Chicago Tribune found the paint contained 4,500 parts per million of lead, more than seven times the legal limit. Photo by Heather Stone/Chicago Tribune.

Back in 2003, when my wife became pregnant with twins, one of my weekend duties was to go to the grocery store and carefully pick out small amounts of fish. We’d read that most seafood is contaminated with mercury, a metal that could harm fetuses. Pregnant women were advised to eat only a few ounces of fish a week. After I’d weighed deli tuna and selected only small pieces of frozen salmon for a few weeks, I wondered, “How did it get to the point where we have to keep track of how much fish we eat?”

I knew there was an investigative story in this situation. But where?

After talking with my editor, George Papajohn, at the Chicago Tribune, the newspaper decided to do something fairly novel. At least it was for us. We would buy dozens of samples of fish and have them tested for mercury levels at a laboratory. Similarly, in 2007, when we decided to gauge the amount of lead in children’s toys, instead of relying on government figures, we tested more than 800 toys ourselves. Ours turned out to be the largest study of its kind outside of the government’s.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read the investigative project, “Children at risk in food roulette" »Doing rigorous testing ourselves costs money: For each of these two investigations, the cost was about $9,000. Some will be surprised to learn that despite being in bankruptcy, the Tribune continues to support it. Last fall, the newspaper spent $6,000 to test dozens of food products for “hidden allergens.” These are ingredients not disclosed on labels but ones that are potentially deadly to those with allergies. Our testing revealed hidden allergens in a variety of popular brand-name foods from cookies to chili to chicken bites. The result: Hundreds of thousands of such items were pulled from shelves nationwide.

As we look ahead, newsroom managers are discussing increasing our budget for testing products in the future, not decreasing it. Of course, there are benefits to the newsroom being so closely involved with the testing, and some of them include the following that have given us an edge in reporting these public service stories:

- Selecting the items to send to labs for testing forced us to master the subject matter quickly and thoroughly.

- Being able to track the testing closely helped us determine precisely who might be potentially hurt by what.

- Having comprehensive access to the details of test results provided us with clear reporting entry points into what are complex topics.

We found, too, doing the testing in this way elevated our coverage. At a time when many government regulators aren’t doing the kind of protective oversight that consumers want and expect, we could use our investigative journalism to alert the members of the public to health and safety dangers. Also, since we knew so well the methodology of the testing, it would be difficult for our findings to be disputed, though, as we found out, some of them still were.

Fish and Mercury

With the fish story, we wanted the testing to be done with as much scientific rigor as possible. So instead of buying a handful of fish at nearby grocery stores, we began by studying the methodology of similar scientific research and called experts for advice. In the end, we decided to test 18 samples (each) of nine kinds of seafood. To purchase the samples, we randomly selected stores. Doing such a random sampling would remove any biases—even if we might not think we brought any with us to the story. And in this way, too, the results of our testing would be representative of the entire Chicago area.

Fellow Tribune reporter Michael Hawthorne and I spent two weeks battling Chicago traffic to collect fish samples, including salmon, tuna and swordfish. We placed them in zip lock bags, packed them in ice, and shipped them overnight to Rutgers University in New Jersey. There, a lab experienced in mercury analysis conducted the actual tests.

In all, 162 samples were tested, which made this one of the nation’s most comprehensive studies of mercury in commercial fish. We found that much of the seafood was so tainted that regulators could have confiscated it—if only they’d been looking. However, the Food and Drug Administration does not routinely inspect fish for mercury—not in ports, processing plants, or supermarkets.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read the first part of the series “Tribune Investigation: The Mercury Menace: Toxic risk on your plate" »Our test results, published as part of a three-day series in 2005, prompted reforms in both the United States and Canada. Three years later, Congress passed legislation banning U.S. mercury exports so the metal won’t end up on the world market where it might pollute the environment. (At the time, Illinois Senator Barack Obama introduced the bill in response to the Tribune’s series.)

But not everyone embraced our conclusions—or even our testing. In response, the U.S. Tuna Foundation, a lobbying group for canned tuna producers, issued press releases claiming that mercury in tuna was harmless. The industry-financed Center for Consumer Freedom took out a full-page ad in the Tribune and gave us its mock “Bottom Feeders” award for “whipping up needless fears about mercury in fish.”

Toys and Lead

Testing toys for lead was just as challenging, and our stories received a similar backlash from that industry. For $3,000, the newspaper rented a hand-held device called an XRF analyzer for three weeks. It looks like a store-pricing gun on steroids; place its face against an object and pull the trigger, and it quickly estimates the item’s lead content. One night I brought the scanner home and began testing toys in my kids’ basement playroom. After three hours, with several “hits” for lead, I came upstairs and placed the gun on the dining room table.

“What’s that thing?” my wife asked.

“It’s a gun to check for lead in toys,” I responded.

“How does it work?”

“I think it shoots out x-rays.”

“X-rays?” she asked, raising a brow.

“Well, x-rays or gamma rays.”

“I don’t want that thing in the house,” she told me, and that night the XRF gun stayed in the garage. The next day, the manufacturer, as well as a physicist at the Illinois office of nuclear safety, assured me we had nothing to fear, so our testing continued. My reporting colleague Ted Gregory took the scanner and checked toys and other children’s products on shelves of more than 40 Chicago-area retailers including big box stores, toy boutiques, discount outlets, and supermarkets.

Toys that registered over the legal limit of 600 parts per million of lead on the scanner were purchased and then sent to The University of Iowa Hygienic Laboratory to determine the total lead content. Children’s jewelry and vinyl toys that tested high at the Iowa lab were then sent to Scientific Control Laboratories in Chicago for additional testing to determine whether the lead could leach out if parts of the toys were swallowed. Vinyl toys received even further analyses—“wipe tests”—to determine whether the lead could escape by merely touching them.

In the end, the Tribune identified a dozen toys that violated federal safety limits. Nine more exceeded stricter Illinois limits.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read the first part of this series “Hidden Hazards: Kids at Risk: Many more toys tainted with lead, inquiry finds" »Our story was published in November of 2007, and immediately retailers and manufacturers pulled the majority of unsafe products we’d identified from shelves. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Illinois Attorney General’s office opened investigations. Our testing also prompted several manufacturers to take additional steps: Kids II redesigned its award-winning Baby Einstein Discover & Play Color Blocks, and Ty Inc. remade its popular Jammin’ Jenna doll. With both, these companies replaced lead-tainted vinyl with other materials. And Alex Toys said it would overhaul its entire testing program. The company promised to check materials for lead during their overseas production and then reexamine the toys once they arrived in the United States.

With this story, too, our test results were challenged. Prior to publication, three toy companies disputed the findings we’d shared with them of the Tribune’s findings and threatened legal action. One of the complaints arrived just as we were on deadline to publish the story. The firms claimed that their tests showed their toys were safe, the Tribune’s tests were faulty, and Illinois law did not apply to their products. The Tribune did not back down. Days after publication, these companies pulled their products from shelves.

My advice to those who might consider doing this kind of story: master the science and think big. Plan on not only doing the best study any journalist has ever done on the topic, but try to conduct one of the most valid studies any scientist has ever done on the subject.

There’s no reason why your news organization can’t.

Sam Roe is an investigative reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He was one of the Tribune reporters awarded the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting for his work on the newspaper’s series “Hidden Hazards.”