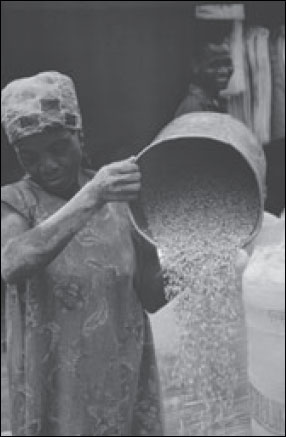

The women of the rice pyramids, Abakiliki, Ebonyi State. Photo by Christine Anyanwu. 2001, Startcraft Intl.©

The Punch, the widest circulating daily in Nigeria, did something savvy October 20. On the cover, Stella, the gorgeous wife of President Obasanjo, was stepping out for an occasion with two equally gorgeously dressed women. There was no detail on where they went; no words heard from them. No stories. Just big color pictures. In this edition, women made the cover, back page, and seven other pages, a total of nine out of its 55 pages. Who can resist the face of a beautiful woman? The paper’s vendors had a field day. That morning, other papers lost out in the fierce competition for a narrowing market.

A content analysis of mainstream media in Nigeria reveals one dominant orientation: Women are largely seen and not heard. Their faces adorn newspapers. However, on important national and international issues, they fade out. Even when the news is about them, the story only gains real prominence if there is a male authority figure or newsmaker on the scene.

Ask any editor in Lagos, the media center of Nigeria, and he will argue his paper is issue-oriented, keen on serious news, and gender-blind. That would tend to suggest that whatever makes news gets covered, whoever is involved gets heard. But the reality is that it is not quite so. The definition of news, what makes news, real marketable news in Nigeria inevitably excludes a sizeable chunk of the population, especially women. By the 1991 population count, women make up 49.92 percent of the population; that is .8 percent less than the men. But from politics to economy, technology, commerce and industry to crime, very few women’s voices are heard in the mainstream media.

At the heart of this practice is tradition. Historically, the local media has been dominated by men, a situation that persists. A recent survey conducted by the Independent Journalism Center (IJC) in Lagos in conjunction with the Panos Institute of Washington and the Center for War, Peace and the News Media of New York established that 80 percent of practicing journalists in Nigeria are male. This circumstance impacts coverage of news. The Lagos-based Media Rights Monitor reports in its January 2001 issue that “domination of the news media by men and the preponderance of male perspective in the reporting of news have also brought about a situation where there is little focus on the participation of women in the political and economic spheres of the country. Women’s issues are also not given adequate coverage in the media. Where they are covered, they are treated from the male perspective.”

Newsmaking itself also has been gender-biased. That a woman made news in the early years of media development in the country was in itself news. “Man bites dog.” “Woman strips in protest against taxes.” It had to be that unusual to attract news coverage. And so, in the early 1960’s, women resorted to doing shocking things in order to grab the attention of society. In Aba in southeastern Nigeria, it took bands of angry women rioting and chasing the colonial government officials there into hiding before society could listen to their issues. Then they made banner headline news in the conservative national dailies.

But those days are gone; that genre of woman has all but disappeared. In her place has come a new brand of woman, doused, softened by education and modernity. She no longer employs the shocking tools of her forebears to get noticed, but she has not succeeded any better with her modern methods. A woman is still largely eclipsed in the news by the looming image of her male counterpart.

The dominant attitude among Nigerian journalists is that women’s issues rarely make marketable news. Controversy is what sells. As most women shy away from controversial issues, they remain out of the orbit of hot news. It is that simple.

But there are occasional sparks. In its October 13 edition, This Day newspaper devoted two-thirds of the back page to a flattering column on Justice Rose Ukeje, the first female chief judge of the Federal High Court and the highest judicial appointment for a female in Nigeria’s history. Some journalists point to the column as indicative of the quality coverage mainstream papers prefer to give women, but it can also be argued that it is reflective of the elitism that rules news judgment in our newsrooms. How many Justice Ukejes are there in Nigeria? For every triumphal story of an Ukeje, there are thousands of her compatriots engaged in unending struggles in a harsh economic and social environment. Their struggles and triumphs are part of the social landscape, which ought to be reflected in the national media.

Mainstream media is dominated by politics. Very little attention is given to real life issues that shape the quality of living, things that dominate the minds and hearts of the people. Professional indoctrination and market realities rule the treatment of information. Women’s issues belong to a genre of information considered lightweight news. Frivolous. No serious editor wants his newspaper trivialized. Therefore, such stories are considered to properly belong to the tabloids dealing in trivia and sex and scandal. In the serious media, they are buried or relegated to the society, art, home and entertainment pages. Only in sports, however, do women speak loudly because of their overwhelming presence and performance.

Branding by advertisers also is a consideration in the treatment of this genre of news. Publications that feature women in large numbers are easily branded women’s publications. That has severe limitations on the kind of advertisements they attract. No publication wants to suffer such limitations in revenue generation. Therefore, they steer clear of such affairs. It is a major nightmare for publications edited or published by women.

Since the voices of politicians drown out the people, it is those few women linked to the noisy world of politics that are occasionally heard. Wives of public officers enjoy the best press in Nigeria. The public profiles of their husbands rub off and the goodwill plays in their favor. Generally, they are perceived as playing supportive roles to their husbands. Women in government also make news but this is because they speak on the portfolios they control, and those usually include women and children’s affairs, health and aviation. Unlike their male colleagues, rarely do they venture out to comment on issues of national importance unrelated to their portfolios.

The visibility of women in elected offices remains surprisingly low despite the significant increase in their numbers in this republic. Like women in other spheres, they are seen more in pictures, and their voices continue to be muffled. In the week of October 15 to 19, for instance, the most contentious political issue in the country was the electoral bill, the law to guide the conduct of the next election. The Senate had passed it with controversial provisions, sparking a noisy debate in the media. In that week, the voices of women in the federal legislature were barely heard. Where were they? Did they not contribute to the debates on the floors of the Senate and House of Representatives? What were their views on the points of contention? It was a mystery.

The silence of women on important national and international issues gives the mistaken impression that they do not care about the things happening around them. However, some female politicians complain that even when they grant interviews, they are either not reported or severely misquoted. As a result, they do not go out of their way to engage with members of the media. Maryam Abubakar, a businesswoman in Abuja, offers another explanation: “Maybe we have not mastered the art of public relations operating here.” Angela Agowike, editorial board member at the Daily Times of Nigeria, however, explains that many women, including those in public office, still do not have sufficient confidence to speak out publicly on issues. “They require a little push; a media friendly environment.”

Agowike belongs to a small group of journalists who through some funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) tried to give women interested in politics a voice in the media during the pre-election politics of 1999. But that initiative petered off with the end of the elections and return of democracy. Before they were properly weaned, they were literally left “on their own” and they slipped back into silence.

Perhaps the most reported issue concerning women in recent months is the traffic of women to Europe for prostitution. Two local NGO’s took it as a cause, focusing on discouraging the practice through tougher legislation and rehabilitating the girls deported from Europe. The activities of the NGO’s have enjoyed considerable media coverage not the least because their flag bearers are the wives of the vice president and the governor of one of the states. That their husbands lent their political weight to this cause helped in no small measure in shaping the attitude of government and by extension that of the media whose huge publicity has made the issue one of the few success stories of media handling of women’s issues in recent times. It could also be argued that their interest in the matter was all the more fired by the tremendous coverage of the global problem of woman slavery and prostitution in the world press. Still, it is a story of triumph. Through sustained publicity and pressure, the federal government has set up its own committee to draft a law that would empower it to seek the repatriation of citizens engaging in such disgraceful practices as prostitution and fraud abroad.

Overall, the coverage of women in Nigerian media is comparatively less impressive than many other nations in the region. But if, as the study by the IJC concludes, this state of affairs can be explained by the overwhelming dominance of males in the profession, are the few women, especially those in decision-making positions, making a difference?

Currently, there is only one Saturday editor and one business editor. There is no female editor or deputy editor in any major daily newspaper in Nigeria. In the magazines, females have made greater inroads with several publishers, editors in chief, executive editors, and associate editors.

Ijeoma Nwogwugwu, business editor of This Day newspaper, explains the low numbers of women at the top. “Many women,” she says, “are hired but they soon marry and drop out of the profession because they can’t combine the rigor with raising a family. Besides, a lot of men are very uncomfortable when they know their wives are going out in the street meeting all sorts of people. They complain of overexposure.” Like many other women who have made it to the top, Nwogwugwu does not believe in gender discrimination in the newsroom, perhaps because she has had a good experience with her peers at her newspaper. Yet many see that as one of the obstacles to the rise in the ratio of women in the profession. One point on which there appears to be consensus, however, is that the majority of male journalists have difficulty accepting the editorship of women. This, they say, impacts on the numbers of female leaders emerging in the newsrooms.

Still, globally, women are moving up the ladder in higher numbers today. Surprisingly, however, it has not translated into more quality coverage for women’s issues, the reason being that professional indoctrination and market realities dictate practice. By their training and socialization, women have been taught that reporting women’s affairs diminishes the stature and impact of a journalist. A professional who wants to be taken seriously goes to mainstream journalism—oil, finance, politics, industry, technology, crime—issues that attract the interest and respect of the dominantly male readership. In Nigerian journalism, this indoctrination is deep, sometimes, driving a strong defensive attitude in the women.

Discussing this issue with four top female journalists, what emerged was that successful women tend to want to remain mainstream and to avoid involvement in spheres that would cause them to be branded. So, they shun women’s affairs and organizations.

“Anything family, any organization that tilts toward women, I’d never be in it,” states Nwogwugwu. “I don’t believe women should segregate themselves. We are competing in an environment. We are all human. We get the same education. We get the same opportunity. Let’s utilize whatever we have and make the best of it.” For this reason, she does not belong to the Nigerian Association of Women Journalists (NAWOJ). Janet Mba-Afolabi, ace crime beat reporter and now executive director of Insider Magazine, does not belong to NAWOJ either. “NAWOJ is trivial,” she says. “My position is that women journalists should belong to mainstream associations such as NUJ (Nigerian Union of Journalists).”

Ronke Odusanya, assistant editor of The Punch, explains that it is the fear of professional labeling that feeds that position: “A lot of us don’t want to be branded as feminists or ‘women’s libbers.’ Their attitude is I’m a journalist. Period.”

Angela Agowike knows the impact this fear has on the quality and frequency of coverage of women’s issues. She was weekend editor of the Post Express before joining the editorial board of Daily Times. “Once you’re writing a story on women in your paper, colleagues tend to conclude immediately that you’re a feminist. A lot of women do not want this. I can understand this. But I tell them this: Somebody has to do it even if it is a way of encouraging others,” she says.

Clearly, the apparent discomfort with gender matters affects the handling of news related to women. “For me it has. Definitely,” admits Nwogwugwu. “I refuse to cover anything related to women. There are all sorts of businesswomen’s forums. Once I get invitations, I throw them in the garbage. I’d never attend them.”

And so, with the attitude set, the rising numbers and profiles of women in the media continue not to yield the expected fruit. Looking at the coverage of news in Nigeria’s mainstream media, the globe has only shifted slightly since those early years when the amazons of Aba and Fumilayo Kutis of Lagos forced society’s attention upon their issues through dramatic public protests. That Rose Ukeje is today the chief judge of the federal High Court; that Ndi Okereke is today the director general of the Nigerian stock exchange; that young Prisca Soares has been making waves as the managing director of the country’s foremost insurance agency, NICON, and that numerous women are today chairpersons of outstanding banks, have not quite changed the dominant attitude toward news about women.

The old notion that their pretty faces are more marketable than their voices still prevails. Agowike is fully aware of where the problem lies and how it can be addressed. “We found that when there’s need for opinions automatically they [journalists] go to men. What we’re saying is that for the proper integration of women, make women’s issues part of what you’re talking about. If it is politics, there are male; there are female. Don’t just talk to only the male. Talk to both.”

It will take a total reorientation of the journalist to hear the clear voice of woman in the Nigerian media. “There are many women with great potential,” Agowike says. “But they need a little push to get there.”

That push, that media friendly environment that will give society the benefit of women’s ideas in the public sphere, is undoubtedly a new challenge for journalism. But is society itself ready?

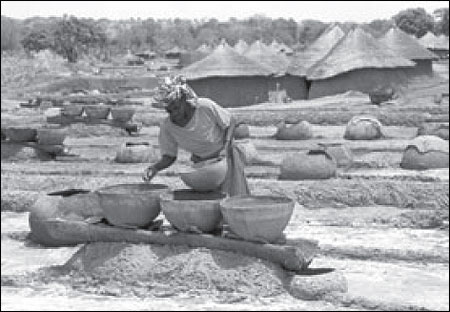

Sifting rice from the chaff, Abakiliki Rice Mill, Ebonyi State. Photo by Christine Anyanwu. 2001, Startcraft Intl.©

A woman at work in the salt pit of Keana, Nasarawa State. Photo by Tony Raymond. 2001, Startcraft Intl.©

Christine Anyanwu is a television programs producer and chief executive of Spectrum Broadcasting Company of Nigeria. Before her detention in 1995 by the country’s military dictator, she was the publisher of TSM, a weekly newsmagazine. Her book on that experience, “The Days of Terror,” was published in December 2001.