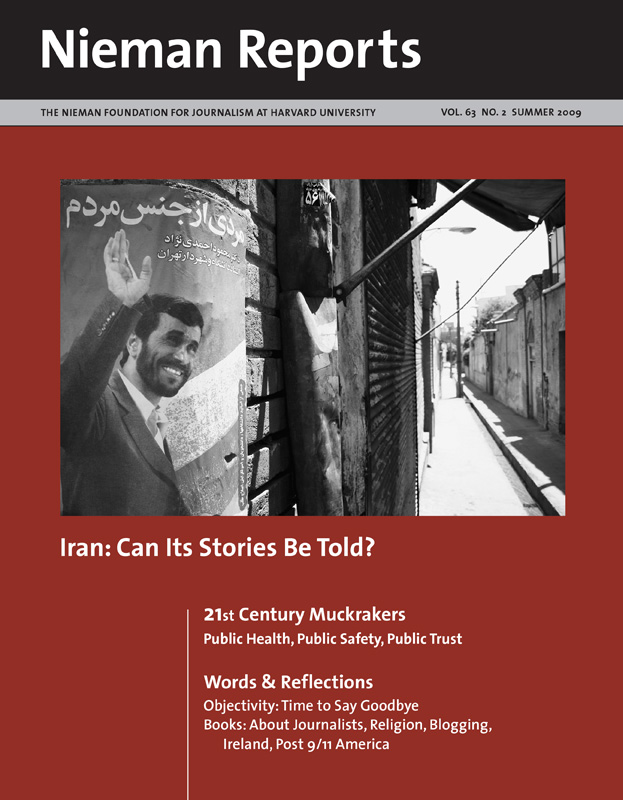

In late April, with Roxana Saberi still jailed in Iran, members of Reporters Without Borders held placards with her picture outside the IranAir office in Paris. Photo by Michel Euler/The Associated Press.

Secrecy, fear and a random justice system are together the currency of oppression. This is how a government typically attempts to buy silence and compliance. And the case of Roxana Saberi, a journalist who was detained in Iran in January, is a classic example of this semisuccessful strategy.

Arrests such as Saberi’s don’t just silence the imprisoned party. They create a freeze, a nooselike hold on Iranian journalists, both domestic and international. It’s incredibly risky for a journalist holding an Iranian passport to speak the truth about what it means to work in Iran without risking life and liberty.

Initial stories indicated that Saberi was picked up on suspicion of purchasing a bottle of wine, which, like all alcohol, is prohibited in Iran. It was later reported that she had been working as a journalist on an expired or revoked permit since 2006 (an exceptionally reckless thing for a would-be spy to do). Saberi was ultimately charged with espionage in March and, after a brief, closed trial received an eight-year prison sentence. Through her appeal, the American-born reporter was released in May.

Now, according to Iranian press laws, reporting without a permit equals illegally gathering news. This can lead to suspicion of spying, especially when the journalist in question reports for foreign media. Iranian authorities say Saberi confessed to the charges against her, though if she confessed to anything at all, it might have been only to working without a permit. Besides, confessing to crimes not committed is pretty much a national pastime. Iranians who are hauled into police stations for various alleged infractions often have the option of writing and signing letters of confession and apology. These letters are kept on file and can be held against the individual on a later date, but nobody wants to escalate a situation in the presence of police.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Attempting to Silence Iran’s ‘Weblogistan’"

- Mohamed Abdel DayemThe good news is that we have no reason to believe that Saberi was physically abused (unlike photojournalist Zahra Kazemi, who was arrested and beaten to death in 2003), and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton took up her cause. The bad news is that Iran didn’t recognize Saberi’s American passport, so it dealt with her as an Iranian, which could have been a dead end. Prominent blogger Hossein Derakhshan—often referred to as Iran’s “Blogfather”—has been detained since November after visiting Israel using his Canadian passport. He faces a potential death penalty.

Another blogger, Omidreza Mirsayafi, died in Evin Prison in March at the age of 29. While the list of people imprisoned, work ceased, and lives ended is long—and most remain anonymous to those of us in the West—Derakhshan and Saberi’s cases are high profile because of connections they have to the Western countries and media. In a not-so-subtle political move, President Ahmadinejad has taken the exceptional step of asking authorities to reconsider their cases.

Of course, being a journalist in Iran has always been a challenge. The former shah also required journalists to have government-issued permits in order to work. Licenses were revoked, and journalists were imprisoned for publishing stories that were deemed unfavorable to the crown. Yes, things were bad even then.

In “Journalism in Iran: From Mission to Profession,” Hossein Shahidi chronicles the extent to which the SAVAK, the shah’s intelligence organization, controlled the press, cracked down on dissent, and how that level of censorship affected the relationship between the public and the press. “There was such deep distrust in the Iranian press in the last decade of the shah’s rule,” wrote Shahidi, “that it was often said that the only truth in the papers was to be found in their death notices.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"No Man’s Land Inside an Iranian Police Station"

- Martha RaddatzWhile most Iranian journalists have to operate with extreme caution, foreign journalists can be more frank on the issues they face in Iran. ABC News Senior Foreign Affairs Correspondent Martha Raddatz, for example, wrote a piece for abcnews.com on tangling with Iranian authorities in September. But then, Iran seldom arrests foreign journalists. Once in a while an Iranian, such as Azadeh Moaveni, gets away with the unthinkable—writing freely outside Iran and returning to the country without getting a private ride straight to Evin Prison.

Of Moaveni’s return to Iran, the author and reporter writes in “Honeymoon in Tehran: Two Years of Love and Danger in Iran”: “My ulterior motive was to discover whether I could return at all. In the two years that had passed since my last visit, I had published a book about Iran that was, effectively, a portrait of how the mullahs had tyrannized Iranian society and given rise to a generation of rebellious young people desperate for change.”

Moaveni was lucky, it seems, but that she is free is in a way as disconcerting as Saberi’s imprisonment: Both outcomes seem uncomfortably arbitrary. The uncertainty here is designed to produce alarm, trepidation and silence.

But what is behind the high-profile arrests of semiforeign reporters? Both incidents are seen only as examples of Iran’s unjust, brutal regime. And that might well be all there is to them. And yet—why would Iran complicate things just as President Obama’s administration is making what appears to be a genuine attempt to build a diplomatic relationship? Some speculate that forces in Iran that are aligned against creating any relationship with the United States are involved with these recent arrests. Despite the denial of Iranian officials, is it possible that Saberi was being held in exchange for the five Iranian diplomats the United States has detained in Iraq for over two years? Or was locking her up yet another show of strength to the international community?

There’s also a real sense of justified paranoia present in Iran. The United States has a long, embarrassing history of meddling in internal Iranian affairs, and The New Yorker’s Seymour Hersh has reported on the clandestine U.S. military operations being carried out in Iran as well as the activities of CIA operatives working there.

In the absence of having a liberated, thriving press—one that can not only shine a bright light on the facts but can operate freely and transparently—we’re left with the necessity of having to try to understand, rather than decide to just dismiss, the actions of a government that deals its most severe blows to its own people.

D. Parvaz, a 2009 Nieman Fellow, was a columnist and editorial writer at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer until the paper stopped its print publication in March.