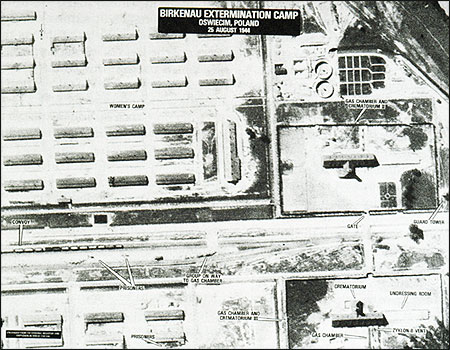

This image of Birkenau death camp taken in August 1944 shows prisoners lined up at gas chambers and other parts of the camp. Though photographed from an airplane, the image is roughly equivalent in clarity and sharpness to those captured now by commercial satellites. Courtesy U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Millions of non-classified, high-resolution images of earth are already available to news organizations. Thousands more are being collected each day. With a little practice, photo editors and journalists can browse large and well-indexed archives of many of these images from their desktops, pinning down overhead imagery of Indian and Pakistani nuclear test sites, newly discovered temples at Angkor Wat, Cambodia, forest fires devastating Central America, or tracking the touchy issue of water politics in California’s farm country.

There has been a lot of hype about this new form of information gathering, yet it is indisputable that medium- and high-resolution images of events on earth gathered by satellites and U-2 surveillance jets are finding their way into the reporting repertoire of print, broadcast and on-line journalists. (Because much of this data about earth are collected outside the narrow bounds of visible light, in the infrared and microwave radar range, then converted to more conventional photos for easier use, scientists use the word “imagery” or “image” rather than photograph.) Among the examples of recent coverage that has relied on these images are the following:

- The New York Times gave front-page treatment to high-resolution imagery of Baghdad made public by the Department of Defense following the December 1998 cruise missile attacks on Iraqi intelligence headquarters.

- CNN played the same images at the top of its news coverage.

- Magazines such as Archeology, National Geographic and Scientific American frequently present analysis based on high-resolution imagery to their readers, as do relatively obscure academic journals such as The Nonproliferation Review and Science and Global Security.

- Modest eight-page monthly newsletters such as the USAID-financed Famine Early Warning System Bulletin regularly compile weather satellite imagery to provide informed estimates of rains and crop health in Africa. And it doesn’t take a rocket scientist, as the saying goes, to see the relationship between Africa’s ecological crisis and the potential for renewed civil war or mass flight of refugees in the Sahel or the Horn of Africa.

Imagery and a related technology, interactive geographic information systems (GIS), seem to be particularly well-suited for on-line publishing of news. Media Web sites such as washingtonpost.com and CBS.com, as well as others, use this technology to enhance their reporting. The Washington Post Web site, for example, includes interactive, multimedia compositions made up of satellite imagery, maps and still photography of Iraq, along with text and “hotlinks” to declassified Defense Intelligence Agency and UNSCOM (United Nations arms inspectors’) documents.

Fully operational sources of satellite images include France’s well-established Systeme pour L’Observation de la Terre (SPOT) satellites, Canada’s Radarsat International, India’s Remote Sensing Agency, Japan’s ADEOS/AVNIR system, the European Space Agency’s Eurimage division, a Russian venture with North Carolina-based Aerial Images Inc and Microsoft Corp., and several U.S. government agencies, to name a few. The world’s largest and most sophisticated archive of satellite and aerial imagery is operated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and housed at the EROS data center near Sioux Falls, South Dakota. (Contrary to popular belief, NASA’s collection of earth observation imagery is considerably smaller than that of the USGS, and it generally ends up being transferred to the EROS center for archival storage. The route traveled by imagery collected by U.S. military and intelligence agencies is usually more convoluted than that of NASA’s. But in the end it, too, usually ends up housed at the USGS.) Presently, almost all unclassified images produced by the U.S. government entities can be studied and used by journalists at minimal or no cost.

We hear often about the potential for U.S.-based private companies to sell high-resolution imagery of earth on demand. This is still an enterprise waiting to be launched. Companies such as Lockheed-Martin and Ball Aerospace, who own significant shares in start-up earth imaging companies, are among the world’s technological leaders in design and construction of earth observation satellites, in part due to multi-billion dollar contracts with U.S. intelligence and defense agencies. But building the most advanced government spy satellite when cost is no object is one thing; building a stripped-down, unclassified version of a similar bird within the cost constraints of the private marketplace is quite another, and it hasn’t been fully realized yet.

The first U.S. corporate launch of a high resolution commercial satellite by EarthWatch Inc of Longmont, Colorado, failed to achieve a useful orbit in early 1998. That company remains competitive, however, due to its Digital Globe imagery index and planned launch of a second satellite in 1999. But it also laid off much of its staff within days of the first failed launch. The Lockheed-Martin/Mitsubishi Industries/E-Systems venture known as Space Imaging Inc. had to delay launch of its commercial satellite for more than a year, but predicts it will have its high resolution satellite aloft by summer 1999. The buzz on the street is that a subcontractor’s laser gyroscopes used to stabilize the satellite’s sensors during flight have tended to wear out more quickly than expected, thus reducing the satellite’s useful life. Space Imaging remains upbeat on its launch plans, but declines comment on the reasons for the delays. For the moment, a dark horse candidate, OrbImage (a subsidiary of Orbital Sciences in Dulles, Virginia) might enjoy the lead among U.S. companies in the race to be first in space with a commercial, high resolution earth orbiting satellite.

There is little doubt that one or more of the U.S. high resolution imaging companies will eventually become commercially viable. During recent months, the National Imagery and Mapping Agency has guaranteed U.S.-based imaging companies purchases of up to $600 million worth of their products over the next five years—and that is before any of the satellites have been launched successfully. (NIMA is the reorganized version of the better known Defense Mapping Agency, National Reconnaissance Office, and several officially non-existent, multi-billion dollar government imagery programs.) Other national governments and major industrial concerns, among them the governments of Canada, South Korea and Saudi Arabia, have offered somewhat similar guarantees. From the point of view of the President’s National Security Council (which sets broad U.S. space policy), the potential for profit and geopolitical leverage derived from the commercialization of these technologies is simply too important to pass up.

Significantly, the news media’s entry into systematic use of the products of these technologies presents challenges and opportunities that relate directly to the core of news organizations’ responsibilities to the public. Earth observation from space provides rich sources of information that can aid reporters in gathering information for stories and publishing their findings. These images are more than an intriguing backdrop for illustrating stories. When used with a geographic information system, such imagery helps readers and viewers analyze and visualize some complex social issues in somewhat the same way skillful weather forecasts concentrate billions of bits of information into a map or diagram that can be readily understood.

The real power of earth observation imagery and GIS are their ability to help illuminate almost any economic, social or political issue that has a geographic component. Better informed, geographically-based reporting can be done on housing and transportation planning in midsize cities, crime control, armed conflicts in Nigeria or along the Turkish/Syrian border, enforcement of arms control or environmental protection treaties, or the tracking of commercial fishing violations off Georges Bank, for example, when journalists learn how to use these sources of information. Even mid-sized news organizations already have the potential capacity to provide comprehensive coverage of county-by-county farm production reports from Illinois, Nebraska or other agricultural centers that can be customized for readers or viewers in those counties by using these technologies.

Prices for imagery range from about $30 to more than $3,000 per scene, depending on the age, source and ground resolution of the image, as well as the volume of purchases. Many imagery companies are responsive to requests from bona fide news organizations for occasional free use of in-stock imagery, as long as a customary source credit and copyright notice appears with the image’s reproduction. Some companies even post an “image of the week” on the Internet which is available to the media to download at no cost. (Those interested should contact the imaging companies directly for details.) Of course, news organizations that demand emergency, first-priority acquisition and processing of new images will have to pay for that privilege, with negotiated prices ranging from $5,000 per image and up. And there is no guarantee that the satellite will capture exactly what the news editor might wish to see. Further, an emergency, one-time consultation with a trained image analyst can cost hundreds of dollars per day.

Today, news organizations should team up with universities, think tanks or appropriate experts to ensure they accurately report what satellites and geographic information systems are able to see. Some observers say the day is not so far off when a large news organization may have image interpretation and GIS experts on staff in much the same way they now employ meteorologists. For the moment, however, news organizations are likely to achieve best results from these technologies, at a moderate price, by building carefully selected computer libraries of data relevant to ongoing stories that are almost certain to remain in the news, such as the Middle East, the Korean peninsula or selected world capitals. For metropolitan-based news media, metro-area data is often cheap, flexible and applicable to stories on a remarkably wide range of issues, including crime, the environment and urban sprawl and debates about new highways or sewer systems.

American University’s School of Communication has helped pioneer such work among scientists and journalists from more than two dozen nations. On-line mailing lists such as satshr-l@american.edu (which specializes in imagery and human rights issues) and imagrs-l@ces.net (for the more technically minded) have begun to trade tips on effective newsroom projects, as well as on identifying the pitfalls and ethical questions that these powerful new tools inevitably raise. Recent A.U. student projects included studies of mining accidents in Colorado and the Philippines, the civil war in Kosovo, and jungle fires in northern Brazil that reached the size of the state of Rhode Island. The school is now working with high school journalists from the Washington, D.C. area to create interactive, geographic Web sites. On these sites, a new generation of journalists is learning how to portray the vital issues for their home neighborhoods using interactive maps, words, imagery and photographs.

If democracy depends on an informed electorate, then potentially, at least, the news media’s use of geospatial technologies can help us look more deeply into places and issues that haven’t been easily accessible. As with meteorology, accurately interpreted earth imagery and interactive maps permit millions of people to see in a few seconds what would otherwise take a half hour or more to explain in words. More than that, when produced judiciously and fairly, this form of information-rich news can enhance the visual appeal of media in similar ways to how the arrival of photojournalism transformed the presentation of news in papers and magazines.

Some caveats are crucial. Commercial earth observation does not create the “all-seeing eye” that some fear (and others want) because it will not be able to achieve that degree of visual acuity. If your company really wants a photo of, say, Barbra Streisand’s wedding, it’s far cheaper and more efficient to hire a small airplane and a photographer, and that option has been open to news organizations since at least the 1930’s. Television news most likely will not enjoy the immediate turnaround for high-resolution imagery that spot news reports require, even though Radarsat International and an experimental European program can deliver four- to six-hour turnaround times between acquisition of an image and delivery to a customer. (While that is an extraordinary advance for the imaging industry, the catch remains that it may take more time than a television news producer can afford for the right satellite to arrive at the right spot at the right time to acquire the right image.)

What earth observation combined with GIS can do is provide glimpses into places closed to reporters and photographers, such as war zones and nuclear test sites. They can vividly compare and contrast options for environmental protection or upgrading transportation systems, and they can document almost any medium or large scale human activity such as the building of a dam—or of a concentration camp. They can reveal the health of forests and help identify urban neighborhoods where construction of a modest clinic could dramatically cut costs at city hospital emergency rooms. And in some instances, GIS computer analysis might help link clusters of disease to specific toxic waste dumps.

The images provide journalists with the raw materials for checking up on international compliance with arms control, environmental and some aspects of human rights treaties. One very important story for which this kind of coverage has already proved invaluable involves the development and deployment of weapons of mass destruction in countries where access by any means other than satellite imagery is impossible.

When designing news projects using these imaging techniques, it is probably prudent for journalists to take their initial cues from scientists, intelligence experts and the major resource corporations who have long used earlier, more awkward versions of earth observation and GIS techniques. And remember that these images are most effectively used to document “big picture” changes over time, changes that take place almost unnoticeably, yet affect the lives of millions of people.

Earth observation and GIS will never replace the emotional power of a close-up photograph of a human face. They do, however, provide powerful tools that can transform and enrich democratic debate or reveal some secret terrors of a dictatorship to the world’s view. Those are rare and valuable instruments in any journalist’s tool chest, and ones that many journalists will want to learn how to use properly.

Three satellite images of the identical Rondonia region of the Amazon taken in 1975, 1986 and 1992. These images vividly illustrate the changes occurring in the rain forest due to illegal clear-cut logging. Images courtesy of USGS/Landsat.

Chris Simpson specializes in information literacy issues at the School of Communication at American University in Washington, D.C. He directs the school’s Project on Satellite Imagery and the News Media. Simpson spent more than 15 years as a journalist and is author or editor of five books on communication, national security and human rights.