Election 2000: Politicians and the Press

It’s the tendency to focus on the celebrity, the character, not serious character but personality traits of political figures that trivializes the political process. So the focus of this discussion will be on issues which might be overlooked or underreported in the 2000 campaigns. Issues like those that David Broder spoke of last May when he wrote in his column that it’s quite a trick for something to grow larger and at the same time become more invisible. Broder was talking about the health care issue then, but he might just as well have been talking about any one of a number of issues that loom ill-defined in the background of the campaign rhetoric that focuses on youthful indiscretions or political money.

– Nieman Curator Bill Kovach opening the political Watchdog Journalism conference

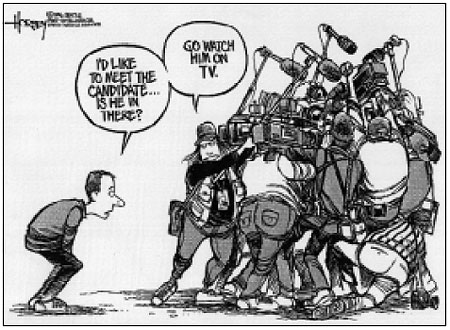

Cartoon by David Horsey. Reprinted with permission, Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Sheila Tate, President, Powell Tate, and former press secretary: “I’ve had the field producer for a major network come to me in September of the election year and say, ‘George Bush will not be on our network tonight because he didn’t throw red meat.’ This meant he didn’t attack Michael Dukakis. He gave a significant speech on education. [And] at that point in the campaign it was vitally important to be on television every night.

“Actually it’s even important what your place is on the show. It affects numbers. It’s just bizarre but it does. And so it doesn’t take more than a few episodes like that to realize that the candidate is being told by television, ‘If you want to be on, start throwing the red meat. Start attacking because you’re not going to be on otherwise.’ And then you might not get elected and you might not have a chance to put all these policies into effect. It’s an ugly process. It really is. I wouldn’t want to go through it again, frankly. Television has an enormous amount of power over elections.”

Judy Woodruff, Anchor and senior correspondent, CNN: “I certainly can’t speak for all of television, but clearly that has been and continues to be a real problem for those of us in television who cover politics. In the heat of the presidential campaign, when we’re vying to see who gets on the air, unless you work specifically for a political program like ‘Inside Politics’ you’re competing with everything else going on in the world and you are concerned about keeping an audience. And those are very real concerns.”

Susan Page, White House Bureau Chief, USA Today: “We’ve got a presidential candidate now in Bill Bradley who’s trying not to follow the traditional way of getting attention. Gore makes a charge, and he declines to respond. He’s going about this his own way and a different way than throwing red meat. We’ll see. I mean, he’s had some success so far, unexpectedly. We’ll see how he does. I wonder also—while television is, of course, enormously powerful—if the profusion of outlets both on cable and C-SPAN and the Internet don’t dilute that somewhat and make it less important what one field producer for one network can do, even if it’s one of the three major networks. It seems to me that the ability they had in 1980, for instance, to really just hold in the palm of their hand a great portion of the American audience is now diminished. That hand is open now, and there are a lot of different places that matter.”

Michael Kelly, Editor in Chief, National Journal: “I wanted to pick up on a point about this power of television and its power to shape campaigns and so on. I think that’s true. But I think one reason it is true or one thing that’s happened that I’d love to see changed in print coverage, in writers’ coverage of presidential elections. It seems to me as if at times we in the writing business have, in covering things that happen, whether it’s politics or in war, that we have almost made some kind of collective decision that television does that job of describing for us. That the camera is so much better at capturing the physicality of something, the event, its reality, that a writer’s chief job is not to describe it, not to paint a picture, a narrative in the way that writers used to. I think this is wrong. I think the camera does not tell the truth, and a writer’s nuanced description can much better capture the truth.

“If you ask the question about why people tune out what we do and why they’re not focused, I think our abandonment of that kind of reporting—our self-conscious narrative descriptive coverage of an event, whether it be political or something else—by a good feature writer in the local paper, robs our readers of a lot of the pleasure of reading about politics. When you hear Alan Simpson talk about the political scene that he’s been part of, there’s a real texture there. And there’s a real sort of vibrant joy and even savage joy to politics. There’s a lot of pleasure in this. We used to have, I think, more writers who understood that part of the business, not the whole business, but part of the business of writing about politics was in a sense to be a dispatch writer. Like you were out covering a war. And to file that kind of evocative textured writing. A certain restoration of that might restore some public interest.”