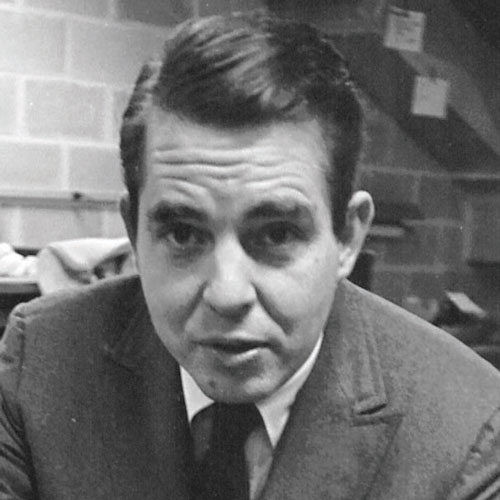

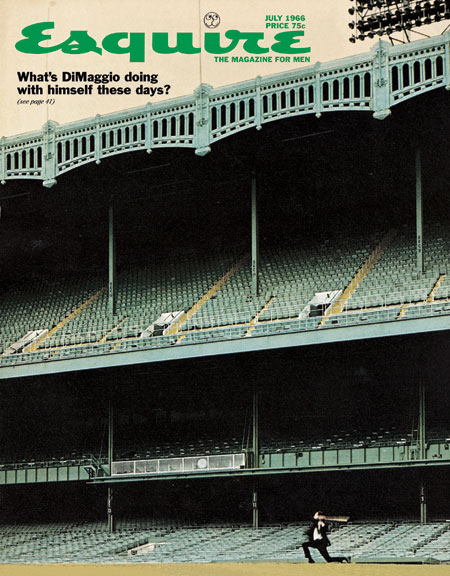

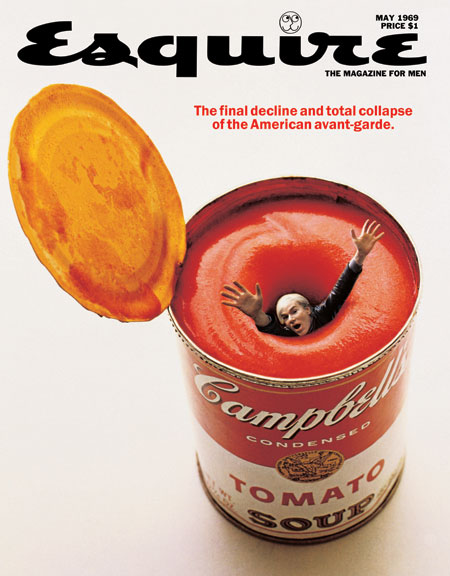

When Hayes (1926–1989) arrived at Harvard, he was locked in a battle with Clay Felker for the editorship of Esquire. A few years later, Hayes triumphed and was named editor in chief, where he reigned for nearly a decade, publishing some of the era’s most memorable writing, including Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe

He was sick of the fighting at the magazine and, besides, he needed more education to handle the kind of material he and the others were trying to get into Esquire. He had been educating himself in the ways of New York intellectual culture, reading magazines like Commentary and Partisan Review; both Felker and Hayes thought the editors of the smaller cultural magazines were setting examples a magazine like Esquire could follow.

But Hayes knew he had a lot to learn. He had been an indifferent student at Wake Forest. He would warn students when he spoke there that the world outside the college was a competitive world in which, he told students, “winners usually win at your expense. Someone else’s victory means your failure.”

Harvard was Hayes’s bid for remedial education. Writing on his behalf to the curator of the [Nieman Foundation], Arnold Gingrich confessed to mixed feelings. Of all his editors Hayes would benefit most from the year at Harvard—an observation that could be read several ways. But Hayes was also the editor Esquire could least do without. Hayes was becoming, in Gingrich’s mind, the “pitch pipe” in the Esquire choir.

As he wrote later in his memoir, “Hayes seemed to have a keen weather eye for the mood changes that were beginning to develop across the country, and particularly among the young, in the late 1950s, and he was good at working up features that appealed to this spreading sense of skepticism, disbelief, and disenchantment.” Hayes used the words “brash” and “irreverent,” Gingrich observed, in an effort to “salt up the magazine’s personality, give it a difference of posture that would set it smartly apart.” Still, Gingrich agreed to let him go, and Hayes became the first magazine editor to get the fellowship. Gingrich not only gave him a nine-month leave of absence but also made up the difference between the modest Harvard stipend and his salary at Esquire.

Eager to begin, Hayes wrote to the registrar in June asking for reading lists for the courses he hoped to take, among them Paul Tillich’s Religion and Society and John Kenneth Galbraith’s Social Theory of Modern Enterprise. Once in Cambridge, he tried to sample as many courses in American intellectual history as he could fit in, just sitting in on some and actually doing the assignments in others, studying under Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Crane Brinton, H. Stuart Hughes, and Oscar Handlin.

Yet Hayes’s courses in intellectual history encouraged him to think grandly—to spin off big ideas for writers, to play the role of sociologist and map the culture. Harvard gave him, too, a better feel for the changes American culture had gone through over time.

From “It Wasn’t Pretty, Folks, But Didn’t We Have Fun? Surviving the ’60s with Esquire’s Harold Hayes” by Carol Polsgrove