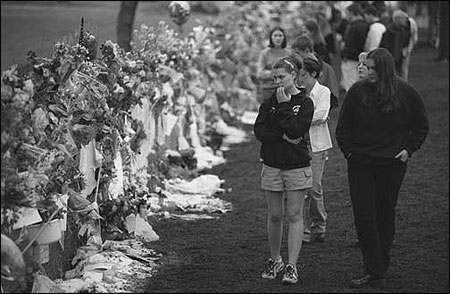

Mourners at the memorial fence. Photo courtesy of The Register-Guard.

May 21, 1998: It became The Day That Changed Everything. It changed everything we took for granted about what it means to send our children off to school. It changed everything we assumed about the stuff that “can’t happen here” and everything we believed about the power of love within a strong and stable family to immunize a child against the plague of inexplicable violence that always seemed to strike somewhere else.

The phone at my home rang a few minutes after eight that morning. Features Editor Bob Welch was calling to tell me he’d just received a frantic phone call from a student who works on the Thurston High School newspaper, The Pony Express. Shots were fired in the school cafeteria. Pandemonium had erupted. During the next 30 minutes we dispatched every available reporter and photographer to the high school and the two area hospitals that were receiving shooting victims.

At nine that morning, I gathered the editors together to map out a plan. We decided right away to cover the shootings more like we would a disaster than a multiple homicide. This meant that our reporting would emphasize victims’ condition, the ordeal of the families, the community reaction, and how people could help.

One of the first calls I received was from John Troutt, Editor and owner of The Jonesboro (Ark.) Sun. His call initiated an amazing series of conversations in which he offered valuable advice about how to deal with this horrific event. He had recently been through a similar tragedy and was almost evangelical in his effort to help us do the right thing. His willingness to share hard-won wisdom about what to watch for in the unfolding hours and days was a compass that would guide us well through this sad and unfamiliar territory.

Nothing in our experience prepared us for dealing with the accumulating horror of the details: four people dead, including suspect Kip Kunkel’s mother and father and two Thurston High School students; 22 students wounded, two of those critically injured. And the suspect was the fresh-faced 15-year-old son of two respected and much-loved educators.

The next morning a spontaneous “memorial” began to take shape along the chain-link fence in front of Thurston High School. People left flowers entwined in the fabric of the fence, and then messages were woven in, followed in succeeding days by stuffed animals, personal mementos and things that took your breath away, like a Thurston graduation cap and gown. I’ve never experienced anything like the feelings I had as I walked along that fence and let the sorrow of a city wash over me. It was a feeling we needed to find ways to convey in the pages of our newspaper.

The poignant words reporter Eric Mortenson wrote about this memorial were, I believe, the kind of journalism our readers needed during this time of anguish and incomprehension:

“Faun Maddux totters down the fence line outside Thurston High School, her blue coat flapping and her short white hair sticking out like iron filings. She just had to come, she says. ‘Had to hop in the car and drive down. Came alone.… I don’t know if I’m the only one here from Vancouver, Washington, but I’m here,’ she says. ‘I had to come see. Even though I wasn’t here, it’s breaking my heart.’

“Join the club. It has a huge membership these days.

“Place a flower or a note on the fence and join the broken heart club. Or just walk down the fence line like Faun Maddux. Ignore the lights of the TV crews who are lined up parallel to the fence line. Ignore the incessant hum of the motors that fire their oppressive death star satellite trucks.

“Say out loud to yourself, like Faun Maddux, ‘This is so hard, you can’t take it in.’

“But it gets in. It gets in and breaks your heart. Walk down the fence line. Ignore the hum of the motors and listen to the silence as the people stand in small knots and read the messages.

“The broken heart club has a huge membership these days.

“Walk down the fence line. See that, in places, the flowers cover the cyclone fence like a vertical carpet…. Like blooms springing out of sorrow.

“Read the notes and feel that clench in your chest again. See the sympathy card from one of the Springfield firefighters, the people who did so much to help. See what he wrote. ‘I am so sorry we could not have done more.’

“He’s in the club….”

Ultimately, our coverage would touch every section of the paper, including sports. Readers told us appreciatively time and again that the distinguishing feature of our approach was the combination of daily “How You Can Help” information and a forum in which readers were invited to offer their suggestions about how to address the problem of youth violence.

The Register-Guard’s archive contains 301 stories on the Thurston High School shootings and their aftermath. Among those are a large number of stories that have examined the issues of youth violence and problems through the eyes of a community that has had to readjust how it thinks about these topics and acts in regard to its children. The response in the wake of this tragedy has been nothing short of phenomenal. Close to half a million dollars has been donated to a fund to help the victims. Schools, social service agencies, mental health centers and at-risk youth programs have begun an unprecedented dialogue aimed at coordinating services and responding to previously unmet needs.

The Register-Guard has joined the community response to the tragedy. We have reported extensively on the plight of parents searching for help with out-of-control kids. Since the shootings we have devoted more of our coverage to examining the capacity of the local social service agencies to meet the needs of the community. The paper continues to explore the causes and consequences of youth violence.

Perhaps the most enduring lesson for us has been that the story of Kip Kunkel and the Thurston High School shootings does not lend itself to reporting that presents easy answers or quick fixes. This story is no more a clarion call for gun control than it is an indictment of school building security. What happened in our backyard is just as much the product of a culture that has grown oblivious to media violence as it is the result of a well-intentioned father’s misguided decision to buy his son a gun. It sets out no foolproof responses for parents seeking to prevent another mixed-up teenager from acting out in deadly anger.

If anything, we’ve only learned that the unthinkable can happen here, and that there is no guarantee that it won’t happen again. The challenge we, as journalists, face is what to do with this ominous lesson. For The Register-Guard, the short-term answer has been to engage the issues raised by the Thurston shootings in ways that help our community heal. Over the long term, the task is more formidable. We must strive to balance coverage of some of our society’s most intractable problems with solution-oriented reporting that holds out hope. We must maintain a keener watch on the complex relationships between our schools and the agencies that support children and families. Finally, we must redouble our efforts to help readers connect the causes and effects of youth violence in ways that they can translate into meaningful community action.

Jim Godbold is Managing Editor of The Register-Guard in Eugene, Oregon.