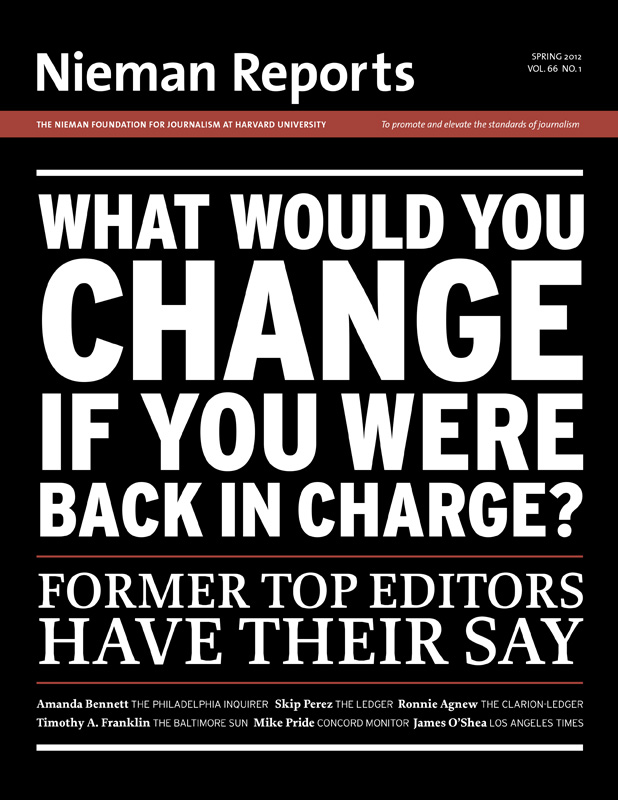

What Would You Change If You Were Back In Charge

Looking back what would they do differently? Six editors take a hard look at newspapers and what it will take for them to stay alive. More investigative journalism, more training, and an embrace of digital initiatives are among the priorities they’d have if they were back in charge. What resonates throughout their essays is the need for coverage that helps citizens and democracy thrive.

When Koky Dishon took over features at the Chicago Tribune in 1975, she didn't tinker. She slapped a "Closed for remodeling" banner on the old Tempo section and the following day redefined the so-called women's pages for all time. Coverage of political rallies ran next to wedding announcements. Sophisticated science reporting crowded out society stories. Bold graphic design replaced stock. Before she was done, Dishon would help launch the "sectional revolution," a national explosion in rich and deeply reported niche feature sections about everything from health to homes to film to food to arts and more. She created sections, killed them when they'd run their course, then built new ones in their wake. The pace of innovation not only upended the "soft news" ghettos of American newspapers, it attracted new sources of advertising revenue to fund journalism that likely saved a generation of readers. These were readers whose newspapers were in danger of becoming irrelevant to lives inexorably altered by changes in the social order.

The creativity she and other editors of her generation brought to the sleepy corridors of newspaper features departments seems easy and obvious now but it was neither. The assumptions they challenged about women readers in particular were as entrenched as any that inhibit journalists today. Moreover, they were arguing for the importance and appeal of content that some of their colleagues viewed as neither important nor appealing. When one leading editor of the time was asked about his plans for his paper's features portfolio, he said, "I love the comics!"

It's hard to do what Dishon did—replace an engine in mid-flight. The horizon—tomorrow's edition—is too close. But journalists are being asked to do that every day, and then the day after that, in the context of a radically altered media landscape. The crumbling of traditional business models and consumption habits has made their efforts ever more urgent, even as resources for supporting those efforts wither.

Dishon's "Closed for remodeling" sign was not mere notice of a redesign but a declaration about the end of one era and her vision for the next. What would that same challenge look like today, and not just for part of a newspaper's operation, but for all of it? With that in mind, we put the following question before a group of accomplished former American newspaper editors from publications of varying sizes and geography:

It is a difficult assignment, even with the benefit of distance. Some former editors who accepted the challenge later demurred, confiding that they struggled with the answers or were concerned about how former or future colleagues would react to their ideas. So we are especially grateful to those journalists who ventured forth. Some of their ideas are tactical, others address fundamental organizational changes; some are about things they would start doing, others are about the things they would stop. What they all share is an abiding intellectual and emotional investment in the struggle for the answer and for the future of the nation's newspapers, even the ones they left behind.

The creativity she and other editors of her generation brought to the sleepy corridors of newspaper features departments seems easy and obvious now but it was neither. The assumptions they challenged about women readers in particular were as entrenched as any that inhibit journalists today. Moreover, they were arguing for the importance and appeal of content that some of their colleagues viewed as neither important nor appealing. When one leading editor of the time was asked about his plans for his paper's features portfolio, he said, "I love the comics!"

It's hard to do what Dishon did—replace an engine in mid-flight. The horizon—tomorrow's edition—is too close. But journalists are being asked to do that every day, and then the day after that, in the context of a radically altered media landscape. The crumbling of traditional business models and consumption habits has made their efforts ever more urgent, even as resources for supporting those efforts wither.

Dishon's "Closed for remodeling" sign was not mere notice of a redesign but a declaration about the end of one era and her vision for the next. What would that same challenge look like today, and not just for part of a newspaper's operation, but for all of it? With that in mind, we put the following question before a group of accomplished former American newspaper editors from publications of varying sizes and geography:

Unencumbered by tradition and with the advantage of some hindsight, how would you organize your newsroom—or one similar—today? Assuming a budget in the ballpark of what you had, how would you deploy your resources to produce compelling journalism and address the needs of news consumers in 2012?

It is a difficult assignment, even with the benefit of distance. Some former editors who accepted the challenge later demurred, confiding that they struggled with the answers or were concerned about how former or future colleagues would react to their ideas. So we are especially grateful to those journalists who ventured forth. Some of their ideas are tactical, others address fundamental organizational changes; some are about things they would start doing, others are about the things they would stop. What they all share is an abiding intellectual and emotional investment in the struggle for the answer and for the future of the nation's newspapers, even the ones they left behind.