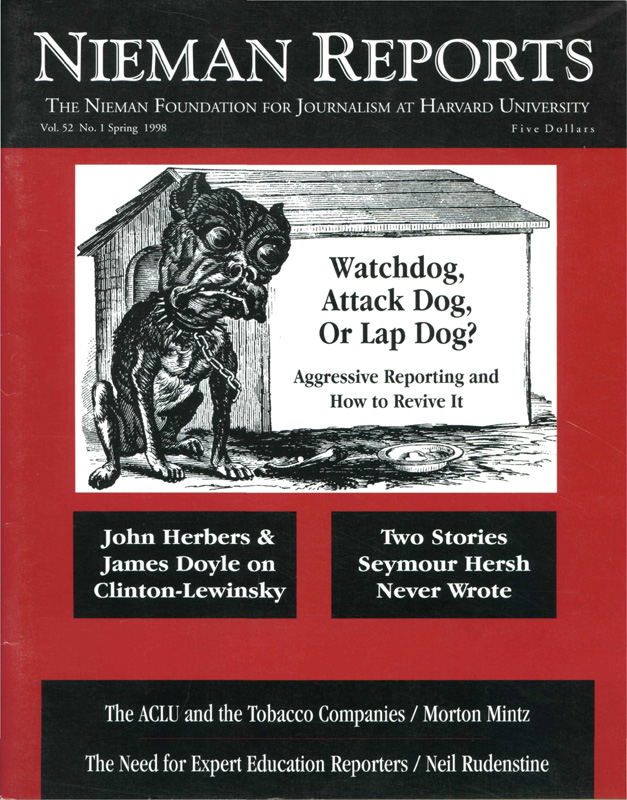

Watchdog, Attack Dog, or Lapdog?

This issue on Watchdog Journalism originated with a call by Murrey Marder, the retired Washington Post Diplomatic Correspondent, for a return to more aggressive, but responsible, reporting. The package begins with two articles on the media's handling of the accusations that President Clinton had an improper sexual relationship with Monica S. Lewinsky. Excerpts from a seminar by Seymour Hersh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter, follow. Then we offer position papers on the status of watchdog journalism in four areas—the economic sector, state and local government, national security and nonprofit organizations.

My assignment: examine the state of "aggressive journalism" in state and local government—whether we do enough of it, whether we are hard-nosed enough, whether we do what we do well enough. Whether solid, watchdog journalism is important.

I can answer the last question with an unqualified yes, it is very important. After that, I run into trouble.

I know how I think The New York Times's Metro section is doing, because as its editor, I see it every day and work with its reporters and editors every day. I can speak with somewhat less knowledge about the other dailies and weeklies in my town. But after that, my insights into papers 1 don't see every day could only be sketchy and anecdotal.

So rather than give readers inevitably facile observations, let me instead focus on why tough reporting is so tough to do, and why, therefore, I think that no newspaper—I'll steer clear of television—can comfortably say it does enough "aggressive" reporting, which falls into two broad categories.

One category is investigative reporting—the vigorous pursuit of wrongdoing and institutional failures, ranging from police corruption to dysfunctional schools. The other category is aggressive reporting of the daily sort, stories answering the "why" of a story, putting politicians, policies and events into smart perspective.

I'd argue that both kinds of reporting are difficult to pull off consistently for a few reasons, starting with this: serious newspapers want to do it all and should do it all. Given the demands of daily local coverage, tough, probing journalism does not come first. It either comes last, or appears erratically, or not at all.

The main reason is, simply, limited resources. Most newspapers don't have the money to employ the number of reporters they need to do it all. Or at least they don't have the resources to do enough of it and that is even more true of local news because the demands on local coverage are greater.

Right or wrong, the conventions of journalism are such that our top priority has to be covering the news—what happened today. That's true even if what happened today was a politician's self-serving news conference that ultimately becomes a 150-word brief inside the paper. And if you're covering your town, city and state, you cover the small, incremental stories as well as the big ones. The further away you get from your subject, the more latitude you have. Foreign reporters have the most leeway, unless they're covering wars or crises.

Every day, local reporting requires that we cover crime. Education. The deaths of police officers. Natural, or near-natural disasters (like a water main erupting on Fifth Avenue). We have to keep up with competition, hopefully lead the pack, and match any story we miss.

Even a cursory reading of local newspapers anywhere in the country will demonstrate that on a given day local reporters are doing all of that and working on a number of news features and columns, to break up the crime and politics.

That leaves too few reporters available to conduct time-consuming and difficult investigations or, simply, to do some analytical writing. While the demands on foreign, national and business reporting are different, all departments in any serious newspaper have to cover so many bases that doing in-depth reporting is not likely to lead the list of priorities. It's just more so when it comes to local and state reporting.

We all watch our governors, legislators and mayors very closely. Mayors and governors have a captive press corps in press rooms usually located right in city hall or the statehouse. These elected officials know they can make news by churning out a press release or delivering a speech or making a provocative remark.

They can easily manipulate us with access. So they do. Even if they fail to get the coverage they want, reporters assigned to them have to listen to their every utterance, if only protectively. That takes time.

When I was covering New York City's government during Kd Koch's mayoral tenure, 1 counted his press conferences and interviews on one typical day: seven. And the city hall press corps had to cover every last one of those that were open to coverage, just in case. Once, when 1 missed a story because I didn't cover a Koch speech that had been billed as routine, I teased him about his getting a surgical implant so reporters would be able to plug in their tape recorders and have an audio record of everything he said, 24 hours a day.

The point is, we have to cover our elected officials diligently, exhaustively, and 1 don't argue with that. We should.

But since we dutifully keep track of what our mayors and governors and aldermen and council members say and do, we have an equal obligation to put their pronouncements and policies into perspective. We are not doing our jobs unless we point out the flaws, the hyperbole, how a promise compares to the last promise on the same subject, its connection to a campaign contributor.

We do not do so consistently enough, and it is even more important today than it used to be because of television, radio and the emerging influence of the Web, which reports so-called news instantaneously, tempting even serious newspapers to violate rules and print unsubstantiated or poorly substantiated "facts."

The news role of the Internet is still in a nascent state; 1 don't think public officials have quite figured out how to game the Web. Not so when it comes to television and radio: media savvy politicians have learned how to avoid the filter of the print press by talking directly to the electronic audience. They know their media market well, they know they are considered a "get"—a sought-after guest—by the local cable channel or news affiliate. They arrange for frequent interviews with news anchors who, because they are general-ists, cannot possibly question them thoroughly, and the television stations are only too willing to accommodate.

So pursuing aggressive journalism in the local press is critical, because if we don't do it, it isn't likely to get done. And for one other reason: the changing roles of government.

Local and state governments are more powerful than ever. Washington has "reinvented" government largely by shifting responsibility to state and local governments. Authority over spending—especially on social programs and education—has devolved from the center, from Washington to localities.

That makes our job as watchdogs even more critical than it used to be. The possibilities for corruption, waste, or simply bad decisions that can hurt the average citizen, are less likely to emanate from some distant bureaucracy in Washington than from around the corner. And given the limits of electronic and Internet journalism, if newspapers do not do substantive local reporting, for the most part it won't get done.

Doing that kind of critical follow-up reporting takes resources—good reporters and more reporters than most of us have. More often than not, the reporter who wrote the original piece is covering the next deadline news development, unable to find the time to do the digging.

In-depth reporting also takes the will to challenge political authority. This sounds elementary, but I think that more than we realize, journalists are too quick to let elected newsmakers—elected officials in particular—set the agenda. Too rarely do we question the basic premise of the speech or pronouncement or policy.

Until very recently, for instance, it has been almost impossible to read intelligent, unbiased analyses of the so-called "drug war." We write story upon story about drug programs and drug related crimes. We quote political leaders and police officers about cocaine busts and how they impact the war. Too frequently, reporters are content to uncritically "cover" drug busts—publicity stunts staged by the police.

But how often do we—not columnists or conservative polemicists, but news reporters—write about the "war" itself, and whether it is being won or even making progress?

That's harder to do because stories like that question the conventional political wisdom and rhetoric and that makes many of us uncomfortable. Traditionally, journalists are not supposed to set agendas; nobody elected us. True. But how narrowly do you define the observer's role?

Not long ago, we defined it very narrowly. I remember proposing to an editor in the early 1980s that we write about a Senate candidates television ads because they were filled with provable errors and half-truths. I'll never forget the editor's answer: "That's for his opponent to do, not us."

Many reporters and editors would have agreed with him at the time and the culture, even at newspapers, changes slowly. Despite the Pentagon papers and Watergate, many journalists were, and some still are, wary of getting ahead of the story.

Probably most of us recognize now that if we are too passive we fail at our central role: informing the public as comprehensively as we can. Assessing political ads, for instance, is a routine part of political coverage these days. And stories that analyze government policies are hardly rare.

This January, for instance, after an undercover officer was killed in a gun battle with drug dealers in New York, The Times wrote a strong piece about undercover drug buys, citing how dangerous they have become now that officers are being lured indoors by drug dealers; in the past, officers conducted buy-and-bust operations outdoors. The piece even quoted police experts questioning the value of the undercover buys in waging what one called "the unwinnable" war on drugs.

It is interesting, though, that in the wake of this officer's death, the city's tabloids did not question the strategy. They were content to devote screaming headlines to the popular theme set by the mayor and governor: eliminating parole for violent felons, since the suspect in the officer's shooting was on parole (though he would have been free anyway, since at the time of the shooting, he would have served his full sentence).

I don't cite this example for competitive reasons, but because it provides a good contrast: smart, analytical journalism, versus predictable, politician-driven journalism.

I think there is another reason we don't do as much aggressive journalism as we could, and this is just as true for local coverage as it is for national, foreign and every other kind of reporting: sometimes it requires us to admit, implicitly, at least, that we made a mistake the first time around, in the initial news story, or at the least wrote incomplete stories. There is nothing reporters or editors hate more than admitting error.

Let me give you two examples.

Mayors of New York City give an annual speech they call their State of the City address. These annual status reports are not required of New York's mayor the way they are legally required of presidents, but mayors going back to JohnV. Lindsay in the 1960s have given them, and why not? They get an hour of free television time and front page stories just for giving a long speech.

Last year, New York City's mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, in a typically upbeat speech, devoted a few sentences to the idea of building a tunnel beneath New York Harbor, to carry rail freight between New York and the rest of the country. This one idea became front page news in The Times (after a debate among editors). There were subsequent op-ed pieces and editorials. Letters to the editor. Television interviews.

What there is not is a new tunnel beneath New York Harbor.

The idea has not advanced. It was evident from the moment Giuliani uttered those lines in his speech that he had jumped on an old idea that has little chance of going anywhere in the foreseeable future—but that sounds good.

It was legitimate to report what the mayor said and many of the caveats about the difficulty of ever building that tunnel were in the original story. But under the pressure of deadline, there was no time to give enough context in the first story. We did write follow-up stories that suggested the plan was mostly wishful thinking. But we had to question our own initial news judgment and be willing to implicitly admit we'd overplayed a story.

Another example is this year's State of the State address by Governor George Pataki of New York. He said he wanted to provide health care to all uninsured children under 19, but provided no details. By the next day, after the story hit the front pages, we found out that the money had already been appropriated by Congress, and that all Pataki was doing was saying, "I'll take it."

We ran a corrective piece, featuring it prominently—but not as prominently as the first day's story. The fact is, catchup pieces don't get the same play, don't have the same impact. But sometimes we can't get the information on time or don't do our homework soon enough. Aggressive reporting, especially the investigative variety, takes time. And, again, resources.

Another example: we frequently report in New York, as do newspapers in other states, government's claims of how many people have moved from welfare to work. But what happened to these people in the long run? Did they find permanent jobs, or did they just give up? Did those who dropped welfare move? How many of those listed on the workfare rosters are the same people who were thrown off welfare, appealed, and got their benefits back? How many welfare mothers who work are getting child care?

Those are just some of the questions that the self-congratulatory political announcements do not answer. The only way to answer them definitively is to get the names of welfare recipients, and former recipients, and interview them. The government will not provide those lists. The Times is in court trying to get them. In the meantime, we're doing as much reporting as we can, trying to learn all we can about what is really going on with the largest workfare program in the country.

Once again we're back to resources.

That workfare project will probably take four months and the investment of four reporters. While they work on that, they are not available for other assignments.

Large, talented staffs are expensive—and spending a lot of money on newspapering goes against the trend in most of the country's newsrooms, even though we'll only be able to hold on to readers in the long run by giving them the depth of coverage they don't get on television.

Newspapers have to do it all. But they cannot cover the fires and the shootings and the press conferences—and undertake compelling projects that take significant commitments of time and staff—unless they keep growing.

Any paper that wants to get beyond the surface has to invest in its staff, and keep investing. Otherwise, we run the danger of being political billboards, and the readers will not only catch on. they will give us up.

Joyce Purnick has been The Times's Metropolitan Editor since June 1997. She is the first woman to head the paper's largest news department. Since joining the paper in 1979, she has covered the state government in Albany, the New York City school system and New York's City Hall, where she became the first woman to head The Times bureau. From 1989 to 1994 she wrote editorials. Purnick then returned to the news department to write the twice-weekly "Metro Matters " column. She has won numerous awards.

Joyce Purnick has been The Times's Metropolitan Editor since June 1997. She is the first woman to head the paper's largest news department. Since joining the paper in 1979, she has covered the state government in Albany, the New York City school system and New York's City Hall, where she became the first woman to head The Times bureau. From 1989 to 1994 she wrote editorials. Purnick then returned to the news department to write the twice-weekly "Metro Matters " column. She has won numerous awards.