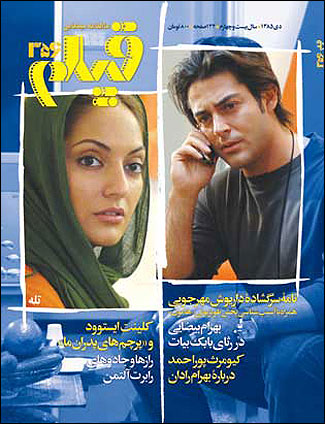

Accompanying Golmakani’s words are covers of Film.

Some imagine Iran as a desert with black mounds, caravans of camels, men with harems, and oil wells. They might be surprised to learn that in this country we have three dailies and two weeklies about cinema and more than 10 film monthly magazines, almanacs, quarterly periodicals, one quarterly in English about Iranian cinema, and dozens of books on the subject published each year.

Why is so much written about film? Perhaps because each year more than 100 feature-length films and 2,000 short films and documentaries are made in Iran. Hundreds of TV shows and films are produced for 10 state-run broadcast channels. (Iran does not have private radio and TV.) Hundreds of students attend four public film colleges, and more private film academies are scattered throughout Iran. A government-owned firm and private companies also make films for release in shops and video clubs. What’s written gets consumed by many viewers of international films, which show up quickly for black market sale on city sidewalks.

Reporting on political matters is a risky business. Journalists have grown accustomed to the shutting down of publications, having to move and start new ones. Under such circumstances, there are two arenas—cinema and soccer—that, while not completely impervious to the political torrents, have a greater margin of immunity.

Film—The Magazine

The first film publication in Iran was published in 1930. By the time of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, there were about 30 publications, the majority of which had very short life spans. During the early years of the revolution—when politics pervaded everything—the production and showing of films was still unorganized, there were no film publications, and the Iranian press rarely paid attention to cinema.

In 1981, a few friends and I decided to start a monthly film magazine; by June 1982, our first issue of Film was published with reviews of some of the better films being released in hundreds of video clubs in Iran. By choosing to feature film criticism—with the approach of critiquing the better films and excluding the weaker ones—Film has deeply influenced filmmakers, government officials overseeing cinema, and created a more serious generation of viewers. Many young Iranian filmmakers tell us that they learned about cinema from reading Film during their childhood and adolescence. At least it can be claimed that during the years of war, political upheaval, social despair, and dearth of film showings, Film kept love for cinema alive.

Now 27 years old, Film is Iran’s longest-lasting publication about cinema. Through the years we’ve increased the number of pages, and since 1986 we have published seasonal special editions, including “Iranian Film Yearbook,” added in 1991. Two years later, we were publishing a quarterly periodical in English.

As happens everywhere, the biggest quarrels that happen with the film industry are about criticism—Film twice faced boycotts by Iran’s Film Producers Union. But this is not the only problem. In the 1980’s, when Film was Iran’s only magazine about cinema, officials in charge of cinema were opposed to the stardom of popular actors. They felt directors and screenwriters should be the stars, which is contrary to the general nature of cinema and the taste of cinemagoers who identify with films through their actors. Yet, in Iran, film publications, until midway through the 1990’s, had to be cautious about framing issues relating to actors.

In these same years, restrictions on the showing of foreign films meant that discussion in our pages about them was also restricted. Rarely was a picture of a foreign film or actor shown on the cover of any film publication. Even though in the past 10 years we’ve seen an astonishing increase in foreign films shown on Iranian public TV—the majority of which are American—those who write about them still risk being accused of “promoting the Western culture” for giving attention to them. Early in 2003, five film critics were arrested on this charge and were imprisoned for one to four months.

To be sure, this type of strict enforcement is not a general government policy. Rather it is the result of the multiplicity of views and actions of government bodies that at times have nothing to do with cultural matters. Film, by maintaining its emphasis on cultivating artistic taste, has continued along the path it carved without coming under the influence of extremist or very conservative sentiments. According to the Iranian saying, it has taken a “slow and steady” walk. This accounts for Film still publishing, while hundreds of publications have opened and been shut down during its lifetime.

Film critique is widely read and desired by Iranians. In the past 20 years, with an increase in film publications and the steady presence of film sections in the public press, the number of film critics has risen noticeably. They now have formed an association, and the 27-year-old Fajr Film Festival in February is the most important film event in Iran. In its early years, film critics would have fit in one row of seats; now at the festival there is one theater with three auditoriums for film critics, writers and reporters. The question and answer sessions after each film showing is so much in demand that sometimes a seat cannot be found.

It’s a love and hate relationship between film critics and the film industry. Ads about films are very limited in the press; in many of Film’s issues we have not one page of film advertisement. And to preserve Film’s independence, most of its ads come from noncinema sources. The relationship we have with the government, as an official supervisory apparatus, is that of principal to student. Like the press in Iran, making of film in Iran enjoys a minimum level of subsidy; the degree of support within a budget can vary depending on the adherence of the film’s subject to state politics.

I write about all of this only out of my experiences with Film, where writing about cinema has given my life meaning. Along the way, I’ve discovered many companions and been connected with many more unseen friends. Sometimes I receive touching letters from readers, old and new, whose letters tell of their attachment to Film in such a way that reading their words brings tears to my eyes. At 55, the smell of ink and newsprint from each issue that arrives from the printing house still overwhelms me, even though I’ve already read every word and know the details of its production. Flipping the pages of each new issue is still so pleasurable that I am unwilling to trade my job for any other in the world, even if it might be easier or higher paid.

Houshang Golmakani is the founder and chief editor of Film, a monthly magazine that has been published in Iran for the past 27 years. International Film, a quarterly magazine published by Film Publications, can be read in English at www.film-international.com.