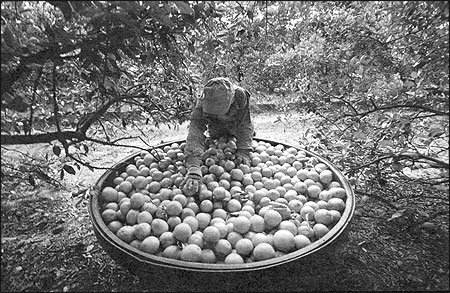

Antonio Martinez tops off a bucket full of oranges in a new job in Florida. He had once been forced to live in deplorable conditions and to work off smuggler’s fees. When Martinez saw money exchange hands between the smuggler and crew leader, he realized he had been sold. Martinez is only required to fill the bins to the bottom of the screws a few inches from the top. However, he must top it off for the crew leader to get his cut. May 2003. Photo by Nuri Vallbona/The Miami Herald.

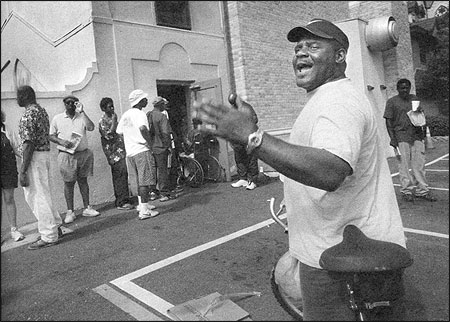

“Anybody wanna go work in North Carolina?”

I was on my knees photographing homeless men lining up outside a Jacksonville soup kitchen when I heard the hearty voice. “Did I hear that right?” I thought.

“Anybody wanna go work in North Carolina?” I turned quickly to see a stocky young man on a bicycle trying to entice the men in line to pick crops in North Carolina.

I had been trying for weeks to get a picture of one of these recruiters, who play a pivotal but shadowy role in Florida’s farming industry. I had staked out positions behind tinted car windows, hoping my lens would be long enough to catch them in the act. “Word must be out on the street you’re out here,” a homeless man once said after I drove 350 miles without snapping one picture.

Now two weeks later this man brazenly rode up behind me on his bike. He was trying to entice men to board a nearby van that would take them to what the laborers in line casually referred to as “the slave camps.” The U.S. government calls it “servitude.” Either way, those who entered the vehicles with promises of warm meals, a steady roof, and all the crack they need, sometimes found themselves in hellholes.

This was one part of the problem Miami Herald reporter Ronnie Greene uncovered as he investigated the rising number of farmworker slavery cases brought in Florida. This series, called “Fields of Despair,” was published in the Herald in 2003. He found that Florida leads the country in the number of contractors who have had licenses revoked because of labor violations against the men and women they lured into the work vans. The wealthy growers who hired these laborers, however, often went unpunished.

Some of the worst abuses were in North Florida, where primarily African-American men were enticed into working the fields only to find themselves sinking slowly into a debt they could never repay. Some of their labor bosses advanced them money for meals and rent, while making drugs and alcohol plentiful. The men had to pay the boss back with 100 percent interest. When payday arrived, they received little or no pay for their 14-16-hour days. Fear of being beaten kept most in the camps. A few escaped by hiking for miles through the woods. They were afraid that if they walked by the highway, they would be found.

As we worked on our series, we’d often ride back from the fields in silence, unable to speak. For me, this story was especially difficult. I grew up in the 1960’s in Texas watching my Costa Rican mother deliberately push her supermarket cart past the bins of purple and green grapes in support of Cesar Chavez’s boycotts. “Hay que apoyar los pobres campesinos” (we have to support the poor farmworkers), she would say after hearing our selfish pleadings, “Just a few little grapes, por favor?”

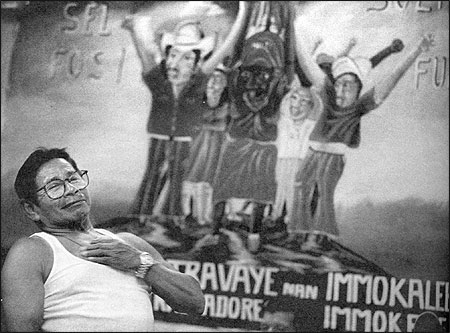

Now, 38 years later, these issues haven’t gone away. It is painful. But working on this story was also inspiring. I met Lucas Benitez, of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, who recently won a Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award for his coalition’s fight against farmworker abuse. Benitez and his colleagues helped free laborers who paid more than $1,000 to be smuggled from Mexico, then saw little or nothing for their sweat and labor plucking tomatoes and oranges—until their smuggling “debt” was retired. Antonio Martinez was housed in a squalid green trailer filled with desperate men. “I realized I had been sold,” he said.

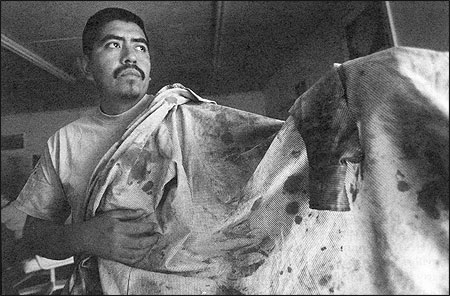

Benitez displayed the bloodied shirt of one beaten farmworker, a vivid memento he had kept for seven years. “When we say that the tomatoes that leave Immokalee have sweat, have blood, we are not exaggerating,” he told us.

Benitez displayed the bloodied shirt of one beaten farmworker, a vivid memento he had kept for seven years. “When we say that the tomatoes that leave Immokalee have sweat, have blood, we are not exaggerating,” he told us.

The result was also rewarding. Our stories prompted Florida Governor Jeb Bush and state lawmakers to pass legislation that increases penalties for farmworker abuse. The governor vowed to create a commission to monitor working conditions. State Senator J.D. Alexander, a citrus grower, said the reforms were prompted by the “Fields of Despair” series.

While these changes are an improvement, I wonder if all the reporting we and others have done will put a stop to slavery in the fields. “How long has this been going on?” I once asked attorney Lisa Butler, who does outreach in farm labor camps. “I don’t know,” she answered. “Years? Decades?” I pressed. “Possibly,” she answered.

Nuri Vallbona, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, is a photojournalist for The Miami Herald. She focuses her work on documentary essays and has won many awards. She was one of 35 Hispanic photographers to work on the book, “Americanos,” which celebrates Hispanic life in America.

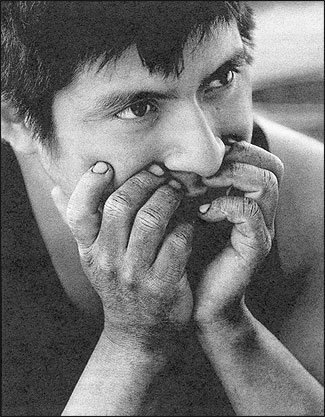

Jose Solano asks for advice from a paralegal with the Migrant Farmworker Justice Project.

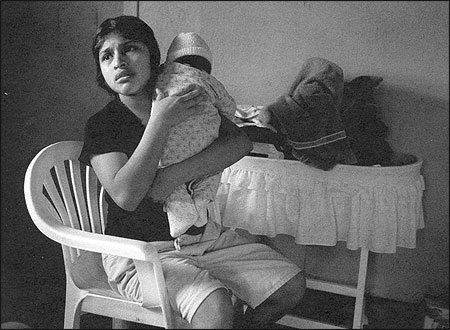

Scared and afraid that she and her husband are running out of money, Rufina de Jesus Santos, 15, asks Raul Barrera of the Migrant Farmworker Justice Project where she can find food in a migrant camp. She had to stop picking tomatoes to take care of her baby. She and her husband still had to pay off the $1600 they each incurred from smuggler’s fees. Barrera referred her to the local church, where she was able to get food on a regular basis. March 2003.

A man identified by former migrant workers as “Jerome” tried to recruit homeless men outside the Saint Francis Soup Kitchen in Jacksonville, Florida, one of several spots that crew leaders use to find workers for their camps. When another man asked him about some workers ending up working for crack, he said, “if they want to work for crack, let ’em work for crack.” July 2003.

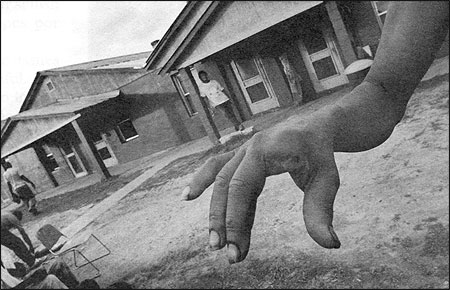

Abuse and neglect compound the problems faced by migrant workers as they try to make a living doing farm work. This farmworker had to have his finger amputated because he did not get proper medical care while he was doing migrant work in North Carolina. April 2003.

Migrant worker Alberto Hernandez listens to activists at a meeting of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers where farmworkers were informed of their rights and told about coalition activities attempting to improve conditions. May 2003.

Photos by Nuri Vallbona/The Miami Herald.