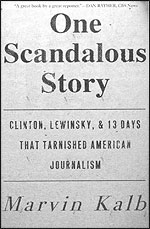

One Scandalous Story:

Clinton, Lewinsky, and Thirteen Days That Tarnished American Journalism

Marvin Kalb

The Free Press. 306 Pages. $26.

For 30 years Marvin Kalb was one of our most respected broadcast journalists (CBS, NBC). Fourteen years ago, he gave that up to become a teacher and administrator at Harvard. But he kept wondering what big changes had occurred in journalism since he left it, and when the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal came along he saw his chance to find out. So he zeroed in on 13 days: eight days leading up to the story’s breaking, the day it broke, and the four following, “when journalists focused on the scandal as if nothing else in the world mattered.”

Indeed they did. On one fairly typical day, the scandal got 20 stories in The New York Times, three on page one; 20 in the Los Angeles Times, five on the front page; 16 in The Washington Post, five on the front page. “Serious” television was just as fixated; Ted Koppel’s “Nightline” had 15 straight broadcasts exclusively on it.

(Not everyone went nuts. On a day when the Post ran 25 stories on the scandal—more than any other newspaper in the country—The Wall Street Journal ran not one major story on it. USA Today and the Chicago Tribune also approached the topic with some caution—for a while.)

Surely Kalb’s study of the press’s overheated reaction will arouse considerable embarrassment in the profession. After all, one must bear in mind this hysteria was caused by an affair that—however regal the setting— was simply mutual seduction resulting in sex between two consenting adults that, until the press made so much of it, had in no way interfered with government. Strictly as a sidebar, but no less important, Kalb raises the issue of right to privacy, which until recently was accorded presidents, yes, even the swinging Mr. Kennedy.

Kalb found, over and over, reporto-rial conduct that, though perhaps admirable for its aggressiveness, was willing to smash and scatter professional standards. He describes these 13 days with phrases like “media madness,” “a frenzied atmosphere,” and “journalism run amok.” And when the media got the scent of semen on Lewinsky’s dress, he writes, “it was a world that had suddenly gone mad.”

Kalb points out that “One Scandalous Story” is the second act of a drama that started in the early 1970’s, when the press brought down President Richard Nixon and his corrupt courtiers. Watergate was the mother lode of fame for The Washington Post and its two intrepid diggers, Woodward and Bernstein. After that, a kind of gold fever seized many editors and reporters—including some at the Post who had been left out the first time around—who yearned to achieve similar fame by sinking their shovels into an equally rich vein of scandal at some later White House.

Given the reputation Bill Clinton had already achieved for womanizing and assorted duplicity as governor of Arkansas, it isn’t surprising that his White House was the chosen one. But for a long while it looked like Clinton would escape his pursuers. At first, the best scandal they could come up with—“Whitewater,” as it was simply known—was a flop. It broke in The New York Times on March 8, 1992, but over the next nine years, neither the press nor federal investigators could show it to be more than a smelly small-scale land deal hatched up years before by Clinton and some of his old Arkansas cronies.

Nevertheless, for a while that “scandal” excited the rest of the press, and the race was on. Leonard Downie, Jr. had been a superb reporter at The Washington Post during the Watergate era but had missed any part of that coverage. Now, as editor of the Post, he could try to make up for it by dominating the Whitewater story which, he later told Kalb, he “loved.”

Indeed he did. “No newspaper, no network, no magazine devoted more time, energy and resources to the Whitewater scandal than The Washington Post,” Kalb tells us. Some of the Post staff, feeling that Downie was overdoing it, agreed with the analysis of Karen DeYoung, who in 1999 was assistant managing editor for national news, that “Len thinks this is his Watergate.”

Finally, in a roundabout way, that’s what this trivial story was transformed into. In 1994, Kenneth Starr, “a partisan Republican with right-wing connections,” was appointed independent counsel by the federal government, with nothing to do but try to look busy with the Whitewater case. After three years he was so bored he thought of quitting. Such thoughts ended on January 21, 1998, the day the Clinton-Lewinsky affair hit the front page of The Washington Post and the rest of the press went bonkers catching up.

It wasn’t the Post’s scoop. It was using material cribbed from the gossipmonger Matt Drudge who, three days earlier, had written on the Internet that Newsweek had “killed” a story about a “sex relationship” between Clinton and a “23-year-old former White House intern.” The (temporarily) killed story had been written by Michael Isikoff. He had once worked at the Post, a most resourceful and often irritating investigative reporter, perfectly willing “to cozy up to felons and other disreputable sources” to get his material. From Paula Jones to Lewinsky, says Kalb, Isikoff “was hooked on the journalistic narcotic of Clinton’s sex life. He pursued one clue after another, one woman after another,” so fervently that even editor Downie got tired of him and Isikoff moved to Newsweek.

The key player in the unfolding of the drama, Isikoff was “for a journalist, in very heady terrain,” and often lost his professional bearings, says Kalb. Isikoff later admitted that he became “beholden to sources with an agenda,” and “I realized I was in the middle of a plot to get the president.” He became not merely a spectator but a central part of the cast.

To some degree, this was also true of most of his major competitors in the press. Many of them had been in Arkansas in the early days of the Whitewater investigation, developing a strong distaste for Clinton and becoming buddies with the extreme Clinton-hating lawyers in and out of government—“the lawyers’ cabal,” to use Kalb’s good phrase—especially those on Starr’s staff, who constantly violated government regulations by leaking anti-Clinton goodies to the press.

At the very front of the scandal was a Dickensian pair whose part in launching it was absolutely vital. Linda Tripp, who was consumed by her hatred of Clinton, betrayed Lewinsky, her supposed friend, by secretly taping their conversations. Lucianne Goldberg, a professional gossip, helped Tripp spread the word.

They were not exactly Junior League types, but Kalb is not concerned with the character of the sources who manipulated the press so much as he is with the atmosphere of almost total anonymity in which they operated. The original Washington Post story quoted 24 anonymous sources. Gone was the Post’s “two-source” requirement that it imposed on itself in the Watergate era. Now one source, however flimsy, was okay. Kalb gives dozens of examples to show that the rest of the press was just as sloppy. Also angering Kalb were the ubiquitous talk shows that, with zilch evidence, endlessly implied that Clinton was about to resign, or—long before it was seriously mentioned in Congress—that he was about to be impeached.

By Kalb’s measure, the major TV news shows used more than 70 percent of their air time discussing the scandal via anonymous sources, unfounded analysis, punditry and pure gossip—such as the “sighting” of Clinton and Lewinsky “in a compromising position.” That was a hot one that really made the rounds (except at The New York Times, where two heroic reporters checked it out, found nothing to it, and refused to mention the rumor).

What hope for reform does Kalb offer? Not much, partly because of the incredible multiplication of TV channels. Broadcasters have found that, “aside from wrestling matches,” talk shows are the most profitable form of entertainment and in some ways imitate the make-believe of wrestling matches. “These shows have managed to befuddle viewers into believing that whatever they see or hear can be equated with news,” writes Kalb.

So what happened to things like foreign news? Don’t be silly. There’s very little profit there. Kalb recalls the old days, his days, when CBS, for example, had a dozen full-time foreign bureaus. Now, he tells us sadly, it has four.

Robert Sherrill has been on the staff of The Nation for 30 years.