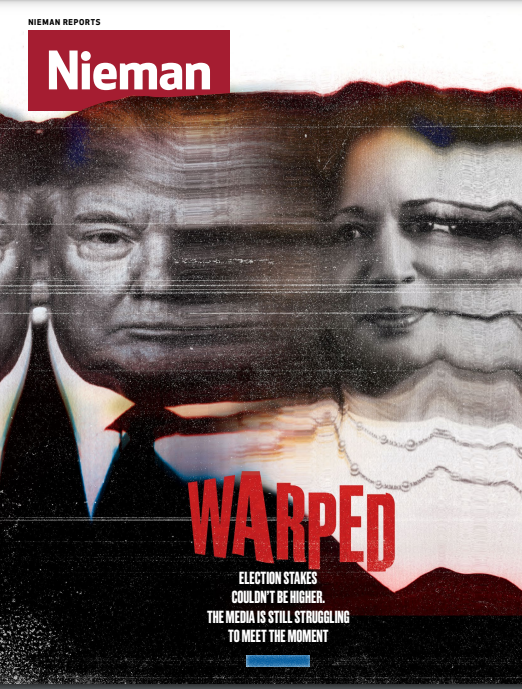

As the U.S. barrels toward a defining election in November, confusion over the news media’s role in American life has only deepened. When a presidential candidate threatens democratic norms and freedoms, should a reporter actively promote the opposing candidate committed to preserving them?

Or are journalists obliged to strive for neutrality by treating the candidates as comparable forces deserving comparable scrutiny? But elevating neutrality, and passively watching an authoritarian gain power, could unravel the press freedoms woven into the fabric of the U.S. since its founding.

Our Summer 2024 issue explores the role of the press when democracy is at stake.

When Evan Gershkovich was freed, the journalism community exhaled. The Wall Street Journal reporter, detained for over a year on sham espionage charges, was released in a prisoner swap, ending a determined campaign symbolized by the “Free Evan Now” buttons pinned to the lapels and backpacks of half the journalists I know.

It’s a start.

In its most recent census of jailed journalists, the Committee to Protect Journalists documented a near record high of 320 behind bars, “a disturbing barometer of entrenched authoritarianism.” China, Myanmar, Belarus, Russia, Vietnam, Israel, and Iran topped the now-familiar list of jailers. Few of their imprisoned are likely to receive the urgent attention given an American working for a major news organization.

Two of them are Nieman Fellows.

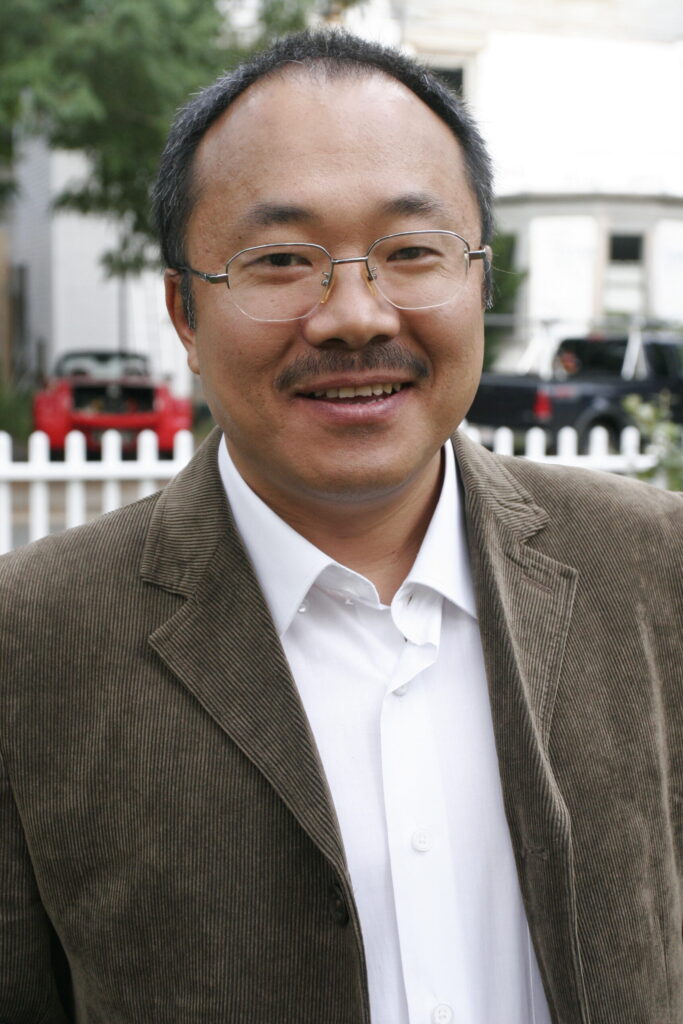

In 2022, while dining with a Japanese diplomat at a Beijing hotel, 2007 Nieman Fellow Dong Yuyu was detained and then tried for espionage. Dong, a veteran editor and columnist at the Chinese Communist Party newspaper Guangming Daily, had long written in support of government reform. He was well known in international circles, and met openly with diplomats, foreign scholars and Western journalists — activities commonly understood as fundamental to reporting, but which have taken on sinister intent in a China increasingly hostile to journalism.

Dong, 62, remains in prison, where he has been awaiting sentencing for over a year. This spring he missed his son’s graduation from Boston University law school.

And on June 1, Truong Huy San, a 2013 Nieman Fellow and prominent Vietnamese journalist, was taken into custody and accused of “abusing democratic freedoms” in his Facebook postings. San, 63, known by his pen name Huy Duc, is an investigative reporter and author of “The Winning Side,” widely regarded as the most significant book about postwar Vietnam but banned in his country. Although his investigations have cost him newspaper jobs and his popular blog was shuttered, his stature and connections were believed by some to shield him from arrest. They did not.

Berkeley historian and Vietnam scholar Peter Zinoman told me that many learned of his detention from a euphemistic Facebook post that in itself conveyed the risk of basic factual reporting in the country. “Saturday morning at 9AM, authorities invited journalist Huy Duc to work with them,” it read. “He returned this evening while they searched his home and then he was taken away again.”

While Dong and San face uncertain futures in prison, other Nieman Fellows are at risk for comparable work. In Peru, 1986 Nieman Fellow Gustavo Gorriti, one of Latin America’s most celebrated reporters, is enduring a vengeful investigation into whether he traded positive coverage for government leaks. Gorriti, whose corruption investigations have taken down presidents and once led to his kidnapping by a Peruvian death squad, could face imprisonment for such charges.

“This is a blatant attempt to muzzle one of Latin America’s best investigative reporters,” said the National Press Club. Gorriti, 76, attributes the campaign against him to government and business “kleptocrats” and says the antidote is more investigation of the kleptocracy.

Dong, San, and Gorriti have all been written about in the Western press. Common to those stories, and to most coverage of imprisoned and threatened reporters, are paragraphs like this one from The New York Times report of San’s detention: “Reporters Without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and PEN America have all called on the government to release Mr. San.”

But Jason Rezaian, a 2017 Nieman Fellow who was arrested on bogus charges of spying while serving as The Washington Post’s Tehran correspondent and spent 18 months in an Iranian prison, believes the scope of the problem now exceeds the reach and resources of our press freedom organizations.

“There was a time, not long ago, when a strongly worded statement of condemnation meant something,” Rezaian told me. “I don’t think we can honestly say they are equipped to handle the volume of press freedom attacks on journalists today.”

Rezaian says the media industry needs to have a difficult conversation about postings in hostile countries and take a “unified stance,” urging Western newsrooms to refrain from sending reporters into Russia “until we have some assurances.” He argues for more open source visual investigations, using the forensic analysis and tools that Bellingcat and some of the larger legacy newsrooms have developed (employed recently in covering Gaza, where the Israeli government has severely restricted journalists’ access).

“We say that taking on risk is part and parcel of a journalist’s work,” said Rezaian, who spent some of his Iranian imprisonment in solitary confinement. “But false imprisonment and being used as leverage for diplomacy is not what we signed up for.”

The operation that secured the release of Evan Gershkovich, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalist Alsu Kurmasheva, and Vladimir Kara-Murza, an author, journalist, and documentary filmmaker, as part of a 24-person prisoner swap, required intense commitment from the Biden administration. But the successful mission does not mask the problems that contributed to the United States’ historically low ranking in the Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 World Press Freedom Index — 55 out of 180 countries, a stunning drop of ten positions in one year.

The organization has since issued a plan for press freedom and asked presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump to commit to its adoption. The first demand: make the U.S. a global leader in press freedom and speak out against violations wherever they occur.

After the last presidential election, advocates lobbied the Biden administration for similar initiatives, including appointing a special envoy for press freedom to identify violations globally. That didn’t happen, though there have been some modest initiatives that point a way toward a targeted approach. Recently the U.S. imposed travel bans on officials in Georgia who supported a law endangering media freedom there and called for visa restrictions on those who misuse commercial spyware to target journalists.

But press protection as a signature American value has not been achieved. If it had, the benefit would redound beyond the U.S., protecting journalists globally, perhaps even in a country like Vietnam, where the State Department says Americans have "trusted partners with a friendship grounded in mutual respect." Vietnam is also the world’s fifth worst jailer of journalists, according to CPJ; when San was detained, he joined 19 other imprisoned reporters.

After San’s arrest, I reread his Nieman application and recalled the persistent hope he held out for a new journalism in Vietnam. After he lost his job at a state-controlled newspaper, he gained a large following as a blogger. When blogging was restricted, he co-founded a new publication. When that was shuttered, he turned to Facebook. Throughout, he maintained a prudent philosophy toward reporting on an authoritarian government: “We chose to approach the line but not to cross it,” he wrote.

San, who served his country as an army senior lieutenant on the frontlines in Cambodia, wrote that he embraced his journalism career with the “tireless spirit of [a] soldier.” But the day after he was arrested, his Facebook account with its 350,000 followers vanished from public view and for the first time since 1989, the year he traded his soldier’s weapons for a pen, he was silenced.

“That authoritarian world view — I don’t want to say it’s winning,” said Jason Rezaian. “But it’s gaining traction.”