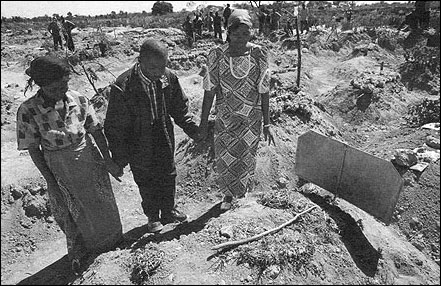

Despite these experiences, I wasn’t prepared for what I encountered at Chamboli Cemetery, a sprawl of knee-high brush, bare earth, and makeshift tombstones in northern Zambia. There the sound of picks and shovels mixes with wailing. Vehicles carrying mourners rise out of the dust and add to the general din as they travel down a dirt road through acres of the wood and scrap metal markers.

It was here, a few miles south of the Congolese border, that freelance photographer Joe Rodríguez and I wound up one morning during our travels in Africa to cover the sub-Saharan AIDS epidemic. This is a slow-motion train wreck of epic proportion: It has killed an estimated 600,000 and infected 1.2 million of the 10.6 million Zambians. Zambia is not the hardest hit of African countries, but the extent of its AIDS epidemic is representative.

There were times when Joe would tell me about how he was experiencing anger along with sorrow and of how he would try to protect himself emotionally by working with his camera to get closer to the people. He’d listen to their stories and share parts of his life with them.

I kept as busy—and distracted—as possible, by reporting, traveling extensively, and taking notes during the day and typing them up at night. I found the writing therapeutic. I worked hard to simply write what I saw with the idea of letting readers decide how they felt about what I observed.

Mourners attend the funeral of a Zambian AIDS victim. Each of them has AIDS, and one of the women has lost three adult children to AIDS and now cares for eight orphaned grandchildren in the nearby Luangwa Township. Of Luangwa's 2,000 residents, 900 either have the virus or have been widowed or left parentless by it. July 2003. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez.

Paying for African Reporting

Joe and I were in Zambia thanks to a grant from the University of Washington’s Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma and the support of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, the newspaper where I am a reporter. Joe and I are both Ochberg Fellows. The Dart Center and the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies established the Ochberg Fellowship to help journalists report responsibly and credibly on violence and traumatic events. Fellows attend a two-day seminar on the role emotional trauma plays in coverage of violent events. Some, like Joe and me, are fortunate to receive a subsidized reporting assignment. This came to me because of my experience covering prisons, and an important part of the Zambian AIDS project was coverage of an AIDS education and detection effort in a prison there.

Louise Seals, the managing editor of the Times-Dispatch, observed that our newspaper could not have afforded to take on the Zambia project had it not been for the Dart Center grant. No international travel had been built into the newsroom’s budget. And Executive Managing Editor Bill H. Millsaps was confident Joe and I would use our grant-funded reporting time to bring to readers an important look at what Africans are experiencing with the onslaught of AIDS. “Behind payroll, newsprint is our second biggest expense. Even so, we had no hesitancy about opening up the space sufficient to adequately display [the] stories and Joe’s pictures,” said Millsaps.

Though stories about Africa are often ignored in small to midsize dailies (our paper has a daily circulation of 190,000), the Times-Dispatch, which is published in a city with an African-American majority, has traditionally run more news about Africa than most newspapers its size.

The Zambian Experience

Our reporting trip began in the sprawling Zambian capital of Lusaka, then moved on to the northern city of Kitwe, south to Livingstone, then back to Lusaka. The groundwork of our journey was laid by Ochas Pupwe, a Zambian student who helped run an AIDS detection and education program in the largest prison in Central Africa. As we quickly discovered, AIDS has hit urban areas in Zambia hard, but the effects of the disease are also evident in the countryside.

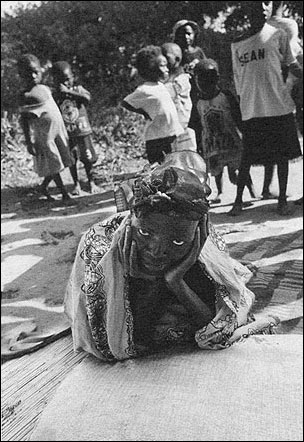

Ignorant of the crocodiles, we were ferried across the Kafue River by boys paddling crude wooden boats to the village of Mufuchani. A short walk up a path bisecting stone and mud brick huts we found Memory Mwape laying on a reed mat in the shade of a tree. Her head rested in her hands. A good meal, much less a physician and antiretroviral drugs, were beyond her means, though her body was ravaged by AIDS. Pain and hopelessness we read on her face turned to an expression of apprehension at our sudden presence. Her husband, Robson Kaingu, whom we learned later is HIV positive, hovered nearby. Children and adults began to gather around us as we talked. Nearby a rowdy group of women drank a homemade brew called chibuku. Mufuchani, with 500 residents, buries five AIDS victims each week.

Memory Mwape, 31 years old, is dying of AIDS and cannot afford medicine. In Mufuchani Village, Kitwe, Zambia, where she lives with her three children and husband, there is no school, clinic, store, running water, or electricity. There are hundreds of AIDS orphans. August 2003. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez.

I’d had little contact with AIDS before I went to Africa, a continent to which I’d never traveled before. It was a place I always imagined was humid, dark and full of wild (but endangered) animals. Its people, I believed, were afflicted by wars, genocide and famine. Joe had been to Africa before and had more intimate contact with AIDS since he’d had friends and relatives die of the disease in Spanish Harlem. He also covered AIDS in Mozambique in 1990. “I knew about AIDS in Zambia,” Joe told me, “but I was quite overwhelmed when I got there. As we walked into different villages and started talking to people, it seemed like every other woman was a widow, every other family had some kids from next door who were orphans.”

Zambia shattered my preconceptions about Africa and AIDS. Zambia, I soon discovered, is a place that shifts from magnificence and generosity to wretchedness and cruelty in a short stretch of time or distance. The AIDS epidemic is largely hidden, since the disease still carries a heavy stigma. Many who are infected refuse treatment so as not to reveal they have the virus. Former prostitutes refuse to be tested and risk further spread of HIV.

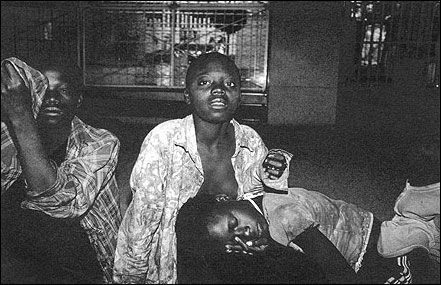

It is, of course, the children who are particularly difficult to cope with emotionally. There are an estimated 600,000 to 700,000 children orphaned by AIDS in Zambia, and there could be as many as one million by 2010, according to the United Nations and the U.S. Agency for International Development. It just takes one or two to break your heart. Many of these children also have AIDS, tuberculosis and other health problems and are too young to know the implications of their illness. Those old enough to remember their parents speak of how much they miss them.

One weekday morning we were surrounded by nearly 90 orphans at a “feeding” station that was organized by a local relief group. There are three such feedings a week for the children who live in the township of Kwacha, just outside Kitwe. Excited by seeing strangers, many of the children surrounded us. They were delighted by receiving the food and seemed happy to be among so many other children they have come to know. “The kids were the ones who kind of threw me back,” Joe said. “The orphans.” Joe told me he was crying inside. We were silent as we sat in the back of a van as we drove away from Kwacha, on our way to visit more widows and orphans.

These Kitwe, Zambian street kids, sniffing glue, are AIDS orphans. No country in the world has a higher proportion of its children who are oprhans than Zambia. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez.

One of Joe’s strongest memories of our trip was something an AIDS worker, Martin Chisulo, who is also HIV positive, told him when asked why Zambians have such large families. It is part of their culture, he replied, and explained that a Zambian is considered a great man when he has many children. “It is the only wealth that we have,” Chisulo said. “We also die a lot, so we must have more children.”

Perhaps because my life has not been touched personally by this disease, I was largely able to remain detached from what I was seeing. It was witnessing the depth of poverty and prevalence of hunger that upset me more than reporting on the disease. Seeing this made me question the idea of universal justice. I found Zambians wonderfully friendly and generous. One tenet of the Dart program is to treat victims of disease and disaster with dignity, and this was an easy thing to do in a country where so many of the people maintain their dignity amid a withering host of indignities. What I found hard to understand is why so many of them suffer so much and so patiently.

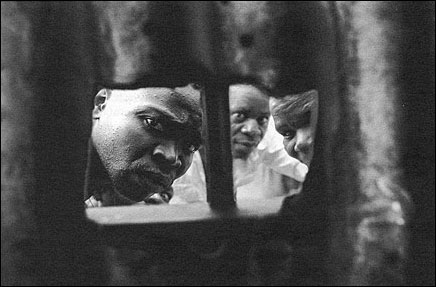

Kamfinsa Prison. In 1999, a Human Rights Watch report complained about crowding in Zambian prisons and jails that led to the spread of respiratory illnesses and other diseases, including AIDS. Kitwe, Zambia, July 2003. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez.

Getting into the Kamfinsa Prison was particularly difficult, but made possible because Pupwe helped run the AIDS project there and knew the warden. Most of the inmates were razor thin, starving on a meager diet of corn porridge served up in large black kettles. Medicine was not available to inmates unless they had friends or family members who could afford to buy it for them. Though the conditions were in many ways far below those found in U.S. prisons, there seemed to be no tension between inmates and the unarmed guards freely walking among them. Also, unlike in U.S. prisons, female inmates were allowed to keep their children with them until they reached school age.

Many Zambians are courageously fighting the epidemic. Yet there is also ignorance, indifference and recklessness when it comes to AIDS.

A high point of the trip occurred on a rutted, cratered road on our way to Livingstone. The red and gold sky as the sun set over the distant Zambezi River cast a soft glow over the landscape. It was chilly inside the cab of the pickup truck, and its cargo bed was full of young Zambians happy to be riding to the city instead of walking. In the twilight, we passed occasional huts with cooking fires burning. The smoky smell of wood and charcoal was carried by the wind. The driver told us of the time he had been delayed on this road for half an hour while a herd of elephants crossed.

The ride was magical. Though the words I wrote reflected on the death and devastation I saw, this evening’s ride is how I will remember Africa.

Frank Green is a reporter with the Richmond (Vir.) Times-Dispatch. Joseph Rodríguez, a freelance pho-tojournalist, is the author of “Juvenile,” published by powerHouse Books in January 2004.