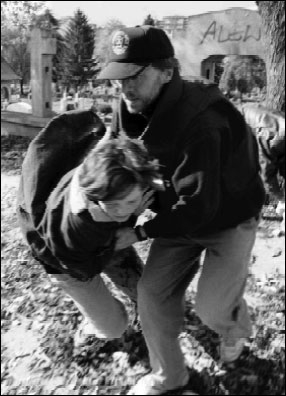

In October 1992, Reuters correspondent Kurt Schork rushed a 13-year-old boy to a car after a mortar exploded in Sarajevo. Photo by Peter Kullmann, Reuters©.

It was a sunny May morning when I was scrolling through the latest wire reports and saw the headline, “Two journalists killed in Sierra Leone.” I winced, as I do whenever I hear of fellow journalists paying the ultimate price for doing their job.

I scrolled down further and suddenly felt the wind knocked out of me. One of the reporters killed was Reuters correspondent Kurt Schork, an old friend from a decade ago when we were both freelance journalists in Southeast Asia. Kurt had come to the region with his then-girlfriend and my colleague, National Public Radio correspondent Deborah Wang, ditching his public sector job to try his hand at journalism, at the age of 42. From the beginning, Kurt struck me as being thoughtful, funny, skeptical and wise. He threw himself into his new calling with energy and discipline.

Then came a day in August, not many months after Kurt had taken up journalism. He and I and Deb were in a car coming back from Vietnam’s border with China, where we’d been reporting a story on black market trade. Kurt had his ear to his short wave radio, trying to decipher the crackle as the car bumped along the dirt road, weaving around cows and bicycles.

“Hey, Iraq has invaded Kuwait!” he exclaimed. We all strained to hear, and when we’d lost the signal, we speculated about how the United States might react. Four months later, Deb and Kurt were on their way to cover the Gulf War, and from there Kurt began his rapid trajectory to becoming, by many accounts, the most respected journalist covering Bosnia—the gold standard against which other reporters judged whether they’d gotten the story right.

Kurt’s death, at age 53, and the death of his friend, Associated Press cameraman Miguel Gil Moreno, age 32, shook many foreign correspondents deeply. Both men were admired for their courage, their integrity, and their judgment, and respected for their considerable experience in war zones. True, on this particular day they were reporting in notoriously unstable Sierra Leone, where 15 journalists have been killed since 1997 (by the count of the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists). And true, as wire service reporters, they chose not to report the story from the relative safety of Freetown.

But having decided to venture out, they took the usual precautions. They traveled in a group for safety and for companionship, with Reuters’ photographer Yannis Behrakis and Reuters’ cameraman Mark Chisholm. They proceeded with caution on unknown roads, asking at a checkpoint whether the road was safe ahead. They were told it was. Not long after, a group of about a dozen militiamen in T-shirts ambushed the convoy. Kurt and Miguel, both of whom were driving, were shot and killed instantly. Yannis and Mark were wounded, but escaped into the bush. Four of the armed government soldiers traveling with them, as escorts, were also killed.

The Guardian’s Julian Borger, who had reported with Kurt and Miguel in Bosnia and East Timor, wrote that they and the two other journalists traveling with them “were all brave, but aware of the risks involved in their work and alert to the need to reassess them and control them at all times. Any reporter who knew them would have felt confident to have accompanied them.”

“But risks can never be calculated entirely,” Borger said. “The ground can shift beneath your feet without warning, especially in as fluid and unpredictable a place as the Sierra Leone bush…. They would have known that, too, as they set out to do their job.”

Each journalist has his or her own calculus for risk, based on experience, commitment to the story, and something far more personal. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, when I was covering the Cambodian civil war and ethnic conflicts in Burma, I saw young freelance photographers—many in their early 20’s—spend as much time as they could on the frontlines and then brag over beers about how close they’d come to being shot. They seemed to feel exhilarated by the experience, convinced that they were invincible, and eager to rush in for more. I wondered at the time whether they were taking on more risk than necessary, whether what they were doing was more reckless than brave.

I asked myself the same question after staring down the barrel of a revolver in eastern Cambodia, after the U.N.-sponsored 1993 elections. The ruling party had proven to be a sore loser, with one of its factions announcing a “secession” of the eastern provinces. The ploy lasted only a few days and gained the party what it wanted—a significant share of power. But meanwhile, supporters of the victorious royalist party were killed. A U.N. helicopter was shot at. The “secessionists” threatened to kill U.N. workers unless they vacated the eastern provinces.

It was in this setting that I, with the BBC’s Ian Simpson and Australia ABC’s Evan Williams, arrived in Prey Veng. We interviewed frightened U.N. workers taking shelter in the back of their building while U.N. soldiers in flak jackets and helmets kept a wary watch at the front. U.N. vehicles had already been trashed and windows shattered. To get the other side of the story, we tried to walk down a nearby road to the place where we knew the secession leader, Prince Norodom Chakrapong, was holding a rally.

The two soldiers and one plainclothes bodyguard standing at our end of the street had other ideas. As we walked toward them, shouting in Khmer that we were journalists, the soldiers waved at us to back off. When we didn’t immediately stop, the bodyguard scowled, looked directly at me—the one who was speaking in Khmer—pulled his revolver and swiftly leveled it at me, marksman style. I was just a few paces away, and for one heartstopping moment he did not look to any of us like he was going to let me off with a warning. I froze. He kept the gun leveled. I backed off, slowly. He kept the gun trained on me until we were all in our car, driving away in the other direction.

To many a war correspondent, this story is nothing special. Each day of reporting a conflict involves risk and, occasionally, facing down a gun. I had been in other conflict situations, before and since, but had never felt shaken in the same way. The difference, I suppose, was that this post-election period wasn’t meant to be a conflict and, until then, Westerners in Cambodia rarely had been targets. But as Julian Borger put it so well, “the ground can shift beneath your feet without warning,” even after years of covering a country and believing that you know the risks.

Did that Cambodian story on that particular day need to be told? Absolutely. Did we need to defy Cambodian soldiers who were already in a bad mood, by continuing to walk toward them? Probably not. There were other routes to the rally, other ways of getting the information we needed. In this particular case, as in other unpredictable and dangerous situations, the safest journey between two points may not be a straight line.

In an article posted to Kurt’s memorial page, journalists Stacy Sullivan and Ed Vulliamy of The Observer in Britain, said that many of Kurt’s friends were “angered as well as saddened by his death.” They questioned whether Kurt really had to be on that particular road on that particular day, whether he really needed to be covering another war at all. After all, he had finally moved back to the United States with his Bosnian girlfriend, had bought a house in the Washington, D.C. area and had spent months fixing it up, was working on a long-awaited book on Bosnia, and was planning to cover the Summer Olympics in Australia. Why the need to take one more extreme risk?

Both Kurt and Miguel had their own answers to that question. Miguel had been the sole international cameraman to stay in Kosovo during NATO’s air campaign. It was his pictures that showed the world how thousands of Kosovar Albanians were being crammed into trains and deported. Kurt had been known to say that he felt a moral obligation to stay in Bosnia, to get the story out and make the world take notice. He was known for his idealism and his relentless pursuit of the facts on the ground. If civilians were still being slaughtered and maimed in Sierra Leone, Kurt would likely have felt compelled to tell the story.

Another journalist I liked and respected, 30-year-old Financial Times stringer Sander Thoenes, felt a similar commitment. He was killed in September 1999, riding on the back of a motorcycle on a reporting expedition to villages just outside the East Timorese capital of Dili, trying to give terrorized East Timorese civilians a chance to be heard. The East Timorese motorcycle driver said that as he and Sander approached a military checkpoint, Sander worried about the driver’s safety and told him to make a U-turn. The men—in military uniform—shouted for them to stop and then opened fire. One bullet hit the motorcycle’s rear tire. It fell over. The driver ran into the bushes. Sander lay on the ground. From the bushes, the driver later said, he could hear the men approach. He heard one of them say, “Kill him.” Sander’s body was found nearby, a day later. He’d been stabbed, repeatedly; his face was badly mutilated.

In both cases, I have no doubt that these journalists took the risks they took because they believed so strongly that the world needed to hear about the atrocities being committed against civilians, and that governments had to be prodded to act.

From what I knew about Kurt and Sander, they were too professional to take shortcuts, but they were not reckless. They, and Miguel, and many others like them over the years, have been killed because they were doing their jobs the best way they knew how, even if it meant putting their own safety on the line. Their deaths should not make any of us back away from taking necessary risks but, perhaps, could give pause to reflect on which risks are necessary. The answer is different for each individual and for each situation, but the goal remains the same—to get the most complete story possible and to be around to tell it.

Mary Kay Magistad, a 2000 Nieman Fellow, opened National Public Radio’s Beijing bureau. She was NPR’s China correspondent (1995-99), Southeast Asia correspondent (1993-95), and a Bangkok-based contributor to The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and other media (1988-92). She also covered the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide and is currently working on a book on the legacy of trauma in societies that have faced violent social implosion.