Truth in the Age of Social Media

Verifying information has always been central to the work of journalists. These days the task has taken on a new level of complexity due to the volume of videos, photos, and tweets that journalists face. It’s not only the volume that presents challenges but the sophisticated tools that make it easier than ever to manipulate information. This issue of Nieman Reports looks at how the BBC, the AP, CNN, and other news organizations are addressing questions of truth and verification.

It all began with an argument.

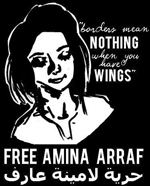

On someone else's Facebook wall is where I first encountered Amina. She was feisty, unapologetic and, though I can't remember what we argued about, I remember her apology afterward, written privately to me in a Facebook message. Soon afterward, we became Facebook "friends," though admittedly we rarely exchanged messages. It wasn't until months later when, after reading a piece in The Guardian about a Damascene "gay girl" whose brave blogging had earned her accolades, I put two and two together and realized that Amina was that girl.

Soon after, however, things took a turn for the worse: Amina, it was reported on her own blog on June 6, 2011, had been kidnapped by Syrian secret police forces. In a matter of just 24 hours, the international media was in a frenzy over Amina's disappearance. But as a few skeptics began to search for someone, anyone who knew Amina personally, her elaborate story began to quickly unravel and by June 12, six days after her supposed kidnapping, the truth became known: Amina was no gay girl in Damascus, but instead a white, American man in Scotland named Tom MacMaster.

Throughout the past year, and even before Amina's story, there has been an abundance of discussion on social media verification, as well as the need for anonymity when reporting from places like Syria. So much of the debate has focused on citizen journalism, the practitioners of which are often deemed prone to errors, that we so easily forget that professional journalists make mistakes, too. Though it was indeed The Guardian that published the story that allowed us to believe that Amina was real, I don't place too much blame on the journalist—the pseudonymous Katherine Marsh—for her error. Though Marsh's editor should have doubted the veracity of the content upon learning that Marsh had conducted her interview over e-mail and instant messenger, I understand all too well why Marsh believed "Amina," because I did, too.

During the six days of the search for Amina, I was directly in touch with those doing the digging and I admit: I at first resisted—and resented—their search. I was at a conference in New York at the time, as was NPR's Andy Carvin—among the first to express doubt about Amina—and I recall arguing with him about whether it was the right thing to do when a life could be at stake. I was upset, angry and wanting to believe.

A sampling of tweets from an effort by NPR’s Andy Carvin to confirm Amina’s existence.

The details about Damascus put forth by MacMaster were plausible, at least enough so that my Syrian friends failed to spot any errors. In fact, as my doubt crept in about Amina, I began writing to our many mutual Facebook friends—mostly Arab women—to ask if any of them knew her in real life. At first, at least two implied "yes," a testament to how much we all wanted to believe that no one could be so callous.

And yet, callous is the first word that comes to mind when I think of what Tom MacMaster did. In an interview with The Guardian in June 2011, MacMaster attempted an apology, stating:

Setting aside for a moment how shallow an apology it was, I am instead struck by MacMaster's foresight in recognizing the damage his hoax would cause. One year later, and the regime has maintained power by doing just that: Portraying the opposition as the real problem, as "terrorists."

And that is precisely why we want to believe each story. We know the horrors that the Syrian regime is capable of, and we know that thousands of Syrians have been killed while others have been imprisoned. We see the videos and the images and hear the desperate pleas on social media. And therefore, when doubt seeps in, we find it harder and harder to believe the next story. One need only look to the conversations taking place every day on Twitter—and even in the major media of some foreign countries—to see how pervasive the doubting of Syrian narratives has become.

And yet, the journalistic errors continue as well. Following the May 25 massacre in Houla in which 108 people, mostly women and children, were killed, the BBC used a photograph of shrouded bodies that had actually been taken in Iraq in May 2003. While the photograph had gone viral on social media, the BBC erroneously posting it led to more accusations of journalistic bias and more doubt.

On a normal day, a journalist's mistake might cost him some respect, maybe even his job. But when reporting on conflict—especially a conflict like Syria, in which journalists are marginalized from the very beginning—a lack of scrutiny may, in fact, inadvertently further agendas of suppression.

Jillian York is the director of international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the cofounder of Talk Morocco.

On someone else's Facebook wall is where I first encountered Amina. She was feisty, unapologetic and, though I can't remember what we argued about, I remember her apology afterward, written privately to me in a Facebook message. Soon afterward, we became Facebook "friends," though admittedly we rarely exchanged messages. It wasn't until months later when, after reading a piece in The Guardian about a Damascene "gay girl" whose brave blogging had earned her accolades, I put two and two together and realized that Amina was that girl.

Soon after, however, things took a turn for the worse: Amina, it was reported on her own blog on June 6, 2011, had been kidnapped by Syrian secret police forces. In a matter of just 24 hours, the international media was in a frenzy over Amina's disappearance. But as a few skeptics began to search for someone, anyone who knew Amina personally, her elaborate story began to quickly unravel and by June 12, six days after her supposed kidnapping, the truth became known: Amina was no gay girl in Damascus, but instead a white, American man in Scotland named Tom MacMaster.

Throughout the past year, and even before Amina's story, there has been an abundance of discussion on social media verification, as well as the need for anonymity when reporting from places like Syria. So much of the debate has focused on citizen journalism, the practitioners of which are often deemed prone to errors, that we so easily forget that professional journalists make mistakes, too. Though it was indeed The Guardian that published the story that allowed us to believe that Amina was real, I don't place too much blame on the journalist—the pseudonymous Katherine Marsh—for her error. Though Marsh's editor should have doubted the veracity of the content upon learning that Marsh had conducted her interview over e-mail and instant messenger, I understand all too well why Marsh believed "Amina," because I did, too.

During the six days of the search for Amina, I was directly in touch with those doing the digging and I admit: I at first resisted—and resented—their search. I was at a conference in New York at the time, as was NPR's Andy Carvin—among the first to express doubt about Amina—and I recall arguing with him about whether it was the right thing to do when a life could be at stake. I was upset, angry and wanting to believe.

A sampling of tweets from an effort by NPR’s Andy Carvin to confirm Amina’s existence.

The details about Damascus put forth by MacMaster were plausible, at least enough so that my Syrian friends failed to spot any errors. In fact, as my doubt crept in about Amina, I began writing to our many mutual Facebook friends—mostly Arab women—to ask if any of them knew her in real life. At first, at least two implied "yes," a testament to how much we all wanted to believe that no one could be so callous.

And yet, callous is the first word that comes to mind when I think of what Tom MacMaster did. In an interview with The Guardian in June 2011, MacMaster attempted an apology, stating:

I regret that quite a number of people are seeing my hoax as distracting from real news, real stories about Syria, and real concerns of real, actual on the ground bloggers where people will doubt their veracity and the fact that I think it's only a matter of time before someone in the Syrian regime says 'See, all our opposition is fake, it's not real.'

Setting aside for a moment how shallow an apology it was, I am instead struck by MacMaster's foresight in recognizing the damage his hoax would cause. One year later, and the regime has maintained power by doing just that: Portraying the opposition as the real problem, as "terrorists."

And that is precisely why we want to believe each story. We know the horrors that the Syrian regime is capable of, and we know that thousands of Syrians have been killed while others have been imprisoned. We see the videos and the images and hear the desperate pleas on social media. And therefore, when doubt seeps in, we find it harder and harder to believe the next story. One need only look to the conversations taking place every day on Twitter—and even in the major media of some foreign countries—to see how pervasive the doubting of Syrian narratives has become.

And yet, the journalistic errors continue as well. Following the May 25 massacre in Houla in which 108 people, mostly women and children, were killed, the BBC used a photograph of shrouded bodies that had actually been taken in Iraq in May 2003. While the photograph had gone viral on social media, the BBC erroneously posting it led to more accusations of journalistic bias and more doubt.

On a normal day, a journalist's mistake might cost him some respect, maybe even his job. But when reporting on conflict—especially a conflict like Syria, in which journalists are marginalized from the very beginning—a lack of scrutiny may, in fact, inadvertently further agendas of suppression.

Jillian York is the director of international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the cofounder of Talk Morocco.