The Documentary and Journalism: Where They Converge

At a time when so much of journalism is quicker, shorter and hyped to grab the public’s presumed short-attention span, the documentary—with its slower pace and meandering moments—is finding receptive audiences in many old places and some new ones as well. In this issue of Nieman Reports, we’ve asked those who document our world to explore how their work converges with ours. How is what they do related to journalism? And what does the documentary form allow its adherents to do in reporting news or exploring issues that other forms of journalism do not?

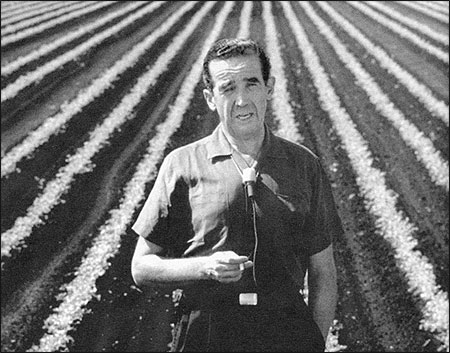

Edward R. Murrow reporting in “Harvest of Shame” about the conditions of migrant farm workers. This “CBS Reports” program was originally shown on Thanksgiving evening 1960. Film image courtesy of CBS Photo Archive, CBS Worldwide, Inc.©

This autumn, for the 12th year in a row, I will take my seat around a large conference table in the historic World Room at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, joining seven distinguished colleagues as we begin three long days of judging the best work in American radio and television. Weeks of individual screening lead up to these final deliberations, which often involve difficult and emotional choices as we glean 12 winners from an original roster of 600 or more entries. This vantage point as a juror for the Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Awards, the most selective and purely journalistic prize in television, has given me a valuable perspective on trends in broadcast journalism.

The picture that emerges is at times inspiring but more often distressing: inspiring because each year there is work that is intelligent, brave, historically important, and deeply moving; distressing because most entries fall far from this mark. Sadly, the commercial networks and the local affiliates have allowed their standards to drop precipitously—in most cases overwhelmed by the financial demands of corporate owners who have little appreciation for the sacred trust that goes with owning a news organization.

This trend is nowhere better or more clearly seen than in the near extinction of the television documentary on the major broadcast networks and their affiliated local stations. This trend has been developing over several decades, but by the mid-1990’s it was clear that the documentary on commercial television was almost extinct.

Some might ask, “Why should we care?” After all, there is still PBS, and many of the cable networks, like Discovery, HBO and A&E, are presenting documentaries even if ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox are not. I’d argue that all Americans should care and care profoundly because the documentary, especially at an hour or more in length, is one of the most powerful forms of human expression. Nothing can take its place; no single report on the evening news, no glitzy television newsmagazine piece, and certainly none of today’s endless TV talk shows have the depth, substance, detail and emotional strength of a well-executed documentary.

Moreover, while the cable networks may be an adequate substitute on the national level, there is virtually no entity to stand in for local broadcast stations in hundreds of cities across America. With local television’s abandonment of the documentary, American communities have lost an important local voice in the examination of key social, political and economic issues. The broadcasting industry should be ashamed of this failure to serve.

The great American documentary tradition is rooted in such powerful progenitors as CBS’s “Harvest of Shame,” which exposed the cruel mistreatment of East coast migrant workers. According to A.M. Sperber, Edward R. Murrow’s biographer, “‘Harvest of Shame’ burst upon the public, an updated ‘Grapes of Wrath,’ a black-and-white document of protest ushering in the sixties on TV.” It turned out to be Murrow’s last great work for CBS.

Sadly, we never see work as courageous as this on CBS today, or on any of the other major networks for that matter. And it is not just the great documentaries like Murrow’s that are gone. In recent years, the documentary as a genre of work has nearly vanished from the traditional networks and the local affiliates.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Striking a Balance Between Filmmaking and Journalism"

- Michael KirkIn an effort to quantify this observation, we asked ABC, CBS and NBC to provide the title and a brief description of any hour long (or longer) documentary they broadcast in 1965, 1975, 1985, and 1999. Perhaps it is not surprising that none of the networks was able, or willing, to provide the information. We made a similar request of six local television stations that have historically been considered among the very best in the industry: WBBM-TV, Chicago; KRON-TV, San Francisco; WCVB-TV, Boston; WFAA-TV, Dallas; WCCO-TV, Minneapolis, and KING-TV, Seattle. Here, too, none could provide a useful amont of information, if any.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Where Journalism and Television Documentary Meet"

- Cara MertesFortunately for Americans, the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) has maintained a strong documentary presence. One standout is “Frontline,” produced at WGBH-TV in Boston, arguably one of the most brilliant and substantive documentary series ever created. “Frontline” has been showered with major awards including the George Foster Peabody Award from the University of Georgia, often called the Pulitzer Prize of television, and two duPont-Columbia Gold Batons, its highest honor. Also “American Experience,” the documentary series “P.O.V.,” and other independently produced but PBS-aired documentaries add further diversity and intellectual richness.

As for cable, I have screened some truly outstanding documentaries from the Discovery Channel and HBO, among others. But in my experience the cable network documentaries are, for the most part, much weaker journalistically, and they are packaged more for their entertainment value than for the enlightenment of the audience. Of the cable networks, HBO has probably made the strongest commitment to documentaries, for which it should be commended. However, HBO’s documentaries lean heavily toward a cinéma vérité non-journalistic style which works well for some subjects but is not conducive to more complex issues.

CNN has also made worthy contributions to the documentary tradition, although it has never achieved the same level of performance here that it has in its breaking news coverage. Neither of the more recent entrants into 24-hour cable news, MSNBC and Fox News Channel, has shown any discernible interest in documentaries.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Remembering Documentary Moments"From the mid-1980’s on, both the quantity and the quality of documentaries produced by the broadcast networks and local stations fell dramatically. Yet the seeds of the decline of the television documentary on commercial television can, in fact, be traced back to the late 1960’s when professional observers began to notice problems. The duPont-Columbia Survey of Broadcast Journalism for 1968-69 asked nearly 500 television stations located in the top 100 largest markets to report on their documentary work during the prior year. Stations were asked to list locally originated documentary programming in 12 subject areas which the duPont-Columbia jurors felt were of major importance. The categories in this survey still read today like a lexicon of significant social issues, including international affairs, politics, birth control and population, disarmament, youth and education, the urban crisis, environment, poverty, crime and violence, medicine, psychology and religion, science and space.

The survey results were dismal. “Documentary programming in the traditional sense of the term had hit a new low,” the duPont-Columbia jurors stated. “The decline of the serious controversial television documentary…can be traced at least in part to lack of advertising support. This reticence comes almost in equal parts from a fear of boring and of offending the public.” In the year 2001, how quaint that sounds.

Sir William Haley, a former editor of the London Times and director general of the BBC, during a 16-month residence in the United States in 1968-69, agreed to serve as a duPont-Columbia juror. His observations about American broadcast journalism are fascinating to read in the context of today’s even greater decline in standards. “It is not enough to say that news must never be thought of as part of entertainment,” Haley said. “News must not be thought of merely as part of a television program. News—and in this word I include…news documentaries—is the life-blood of democracy. Without free, full, and uncontaminated information on all things that matter, the people have no sound means of making choices and deciding.”

Think of the important national and local issues facing the American public today: health care funding, missile defense, a sliding economy, grave energy problems, global terrorism, improving primary and secondary education, Social Security funding, campaign finance reform, poverty, immigration policy, and the list could go on and on. How can it be argued that we do not need, and need badly, the insight which well-researched and well-produced documentaries could provide?

Another survey, done in 1980, took note of an important factor behind the decline—the rise of the network television news magazine. It observed that, ironically, the success of “60 Minutes,” in particular and “the rush to imitate it seemed to diminish the likelihood of any of the three networks finding prime-time for the regular airing of hour-long documentaries.” The reasons were that the magazine format was being given priority and “subjects worthy of extended treatment were appropriated for briefer magazine-length attention.”

A similar problem was afflicting local television. The 1980 survey noted a decline in the number of documentaries getting on the air and in their place “was a dramatic rise in the number of mini-documentaries strung through regular newscasts.” The jurors said that in some cases these reports “added up to worthwhile coverage of substantial topics,” but more frequently they dealt with sensationalized topics.

Any viewer of television news in the intervening 21 years has seen a profound escalation of this phenomenon. Even a generation ago this survey noted that “these obvious appeals to the morbid interests of the stations’ target audiences were habitually run during the ratings sweeps periods, which determined the prices management could charge for the subsequent quarter’s commercials.” That ratings were figuring increasingly into editorial decisions was admitted by two out of three news directors reporting to the survey. Today, the focus on ratings and the competition for viewers’ attention totally dominate the newsrooms of America. Behind the ratings fixation lies the unceasing demand by owners for increased profitability—this in an industry that has enjoyed enormous profitability, especially at the local station level.

All of these forces have combined to crush the documentary on commercial television. Serious and important international, national and local issues are being ignored. The American people, and American democracy, are not being served.

The solution, however, is not government intervention because government has no place in the newsroom. It is true that the deregulatory fervor, begun under President Reagan and continued in both republican and democratic administrations and congresses since, has had an enormous negative impact on the quality of broadcast news, permitting vast consolidation of media power and placing news organizations in the hands of giant corporations that have little feel for the traditions of journalism. But asking for additional government regulation, particularly in the area of news content, is not the answer.

The solution, if there is one, must come from public pressure and from leadership within the profession and within the television industry. At New England Cable News, documentaries have been a part of our news production for several years, featuring such topics as a breast cancer patient’s decision to choose hospice care over more aggressive chemotherapy and a yearlong exploration of the impact on a small Maine town of the closing of its major employer. This year a high-ranking news executive has been assigned full time to oversee long-form reporting and documentaries, and we added targeted funding for this in our budget.

If only one network and/or one station group would step forward and make a serious commitment to fund and broadcast a set number of documentaries every year, that would send a signal that would be heard loud and clear by its competitors, but more importantly by its customers and viewers. The first to step forward will be rewarded beyond measure both in public approval and in the knowledge that those who are taking it are also making an important contribution to the society in which they live.

Phil Balboni, a veteran journalist, is the president and founder of New England Cable News, the nation’s largest and most honored regional news network. He is a board member and former chairman of the Association of Regional News Channels and a member of the editorial advisory board of the Columbia Journalism Review.