Latino Voices: Journalism By and About Latinos

How is the rapid increase in Hispanic American population affecting communities? What are the economic, social, cultural and educational benefits and hardships brought about by this significant demographic shift? Will the numbers and force of Hispanic voters alter the nation’s political landscape? The questions to be raised and stories to be told vary as greatly as do people portrayed by the word “Hispanic.”

Photo by Joseph Elizer Cordero.

As an editor at a magazine written for, and mostly by, Latinos living in the United States, my sense of duty towards our readers is often accompanied by nagging second thoughts about how much information is too much information.

Some issues ago I pushed this magazine, Urban Latino, to run an article on the tension-ridden relationship between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. At first, the editorial team was excited about igniting a debate on an issue that has been getting a lot of attention in the world press. As I began working with the writer, I started having second thoughts: What would fellow Dominicans think? Would I be airing our secrets? Did other Latinos need to know about this? I could have pulled the story, but decided to run it since any reaction—and I fully expected there to be plenty—would be a step in the right direction. (A couple of letters did reach our offices.)

As an editor and as a writer, I feel I have an obligation to pierce the veil of nostalgia through which many of us remember and imagine our native lands. Sun-swept beaches. Rhythm-endowed mulatas. Colorful ethnic prints. These are part of a stained memory that keeps many of us from embracing and engaging Latin American and Caribbean countries as they truly are. I also take very seriously the task of reminding readers that many of us have become comfortable—some to the point of complacency—with the notion that the umbrella term “Latino” means we’re a monolithic group. When we speak amongst ourselves, no one debates that Chicanos, Cubanos, Dominicanos and Argentinos are quite different from one another. But as soon as conversations open to include “mainstream” participants or references, we obediently form a cultural chorus line that dances to a forced tune.

This seemingly natural response often misleads non-Latinos into thinking that we are in fact monolithic and that any one of us, or any group, can speak for all. There is no real benefit for us in this reaction: We simply do it as a defense mechanism to protect what very little space we have in this society.

At Urban Latino, perhaps it is the brazenness of our youth that propels us to seek out stories that other Latino publications don’t. For example, we have dared our readers to learn about slums in Nicaragua, where girls are forced into prostitution from age 10. We have also reminded those who point fingers at foreign perpetrators that many of the 50,000 Colombian women prostituting themselves throughout the world have their families’ blessings. And we have celebrated the rich African legacy of Honduras’s Garifuna people and their struggle for land and social recognition.

Journalists have an obligation to the truth. We are expected to record events we witness or gather from sources. In many ways, reporters are present-day historians, creating a record of humanity as it happens. However, do some reporters—because of who they are, what they look like, or where they come from—have an intrinsic responsibility to report another kind of truth, a responsibility that can allow them to take sides on certain issues? In light of the blatant prejudice that often passes for news and information, should Latino journalists always report on their communities in order to ensure more balanced and accurate coverage?

“No.” Let me say it again: “No.” We also shouldn’t bear a special burden to educate mainstream America about us. Instead, the responsibility is to arm ourselves with knowledge to combat the deluge of ignorance that floods magazines, daily papers, and the Internet. We must seek out the good and the bad. And we must be willing to own up to both.

For instance, it’s fitting to discuss how some of our cultural beliefs, practices and attitudes—and the misinformation they often lead to—affect our sexual health. In a recent article, Urban Latino wrote of a woman in Chicago who adamantly refused to believe that her husband had given her a sexually transmitted disease. She was convinced of his faithfulness. In the meantime, the attending counselor got him to admit that he had ventured from the marital bed. In another story, we explored how our elderly, as a matter of personal choice or necessity, frequent healers, spiritualists and clairvoyants when they should be examined by medical doctors.

Without undermining the critical role such practices play in our lives, reporters should feel that part of their professional responsibility involves exposing how they might be hurting us. As Latino journalists, we should not be made to feel as though we’re airing family secrets.

Last year, following New York’s National Puerto Rican Day Parade, during which several young women were attacked, Urban Latino published a conversation we had with two prominent leaders. We entitled this exchange “Breaking Our Code.” It was our way of reporting on this story. When these attacks were first seen in snippets of homemade video, we had asked ourselves what we should do about it. Do we make a public statement? Do we seek out some of the people involved? Do we examine the mainstream media’s coverage? We knew we had to do something, but at first we couldn’t figure out exactly what.

Then we started listening very carefully and realized that we were afraid to speak openly and truthfully even to each other. (I suspect it was because of heightened cultural sensitivity since among our editing staff one of us is Colombian, one Puerto Rican, and I am Dominican.) That’s when the only course of action became glaringly clear: We had to talk to respected individuals who could spark a dialogue with and among our readers.

The reaction was astonishing. Our interviewees, CNN correspondent María Hinojosa and former Young Lord Richie Pérez, were so forthcoming and honest it was a painful task to edit their comments to meet length requirements. Our readers were so grateful—women especially. They congratulated us for broaching the subject in a critical way. We were pleased to have set this precedent for ourselves. We continue to seek similar opportunities to initiate this kind of open-ended dialogue.

It is liberating to focus on writing about and editing for Latinos. I seldom wonder about what the mainstream will think if they browse our pages. Instead, I concentrate on thinking critically while reporting objectively.

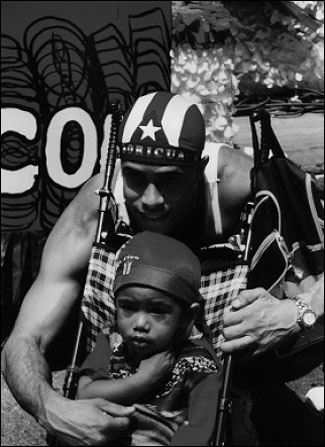

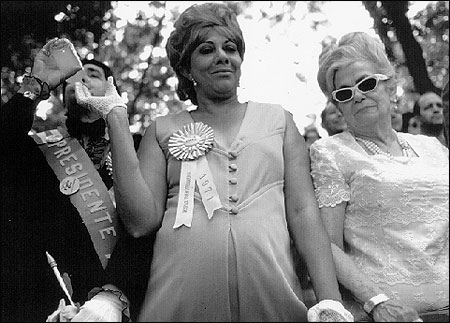

Photos by Pablo Figueroa.

Juleyka Lantigua, managing editor of Urban Latino magazine, is a syndicated columnist with The Progressive Media Project. She was a Fulbright scholar in Spain where she studied Dominican immigration.