Voyages of Discovery Into New Media

At the crossroad of old journalism and new media, digital news entrepreneurs lead us on voyages of discovery into new media. From MinnPost to MediaStorm, these entities are using visual media, interactivity and social media to watchdog government abuse and the justice system, identify environmental dangers, and tell enduring stories. In doing so, they illuminate possibilities.

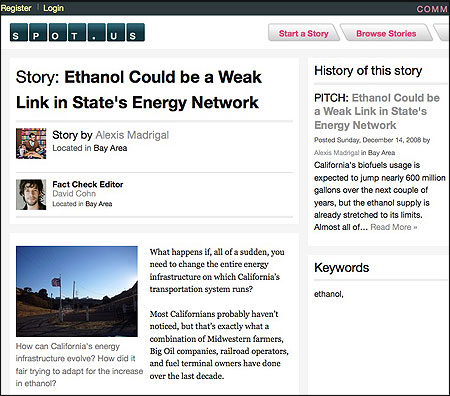

The first Spot.Us story involved an investigation of the role ethanol will play in California’s energy network. Reported by Madrigal, 13 supporters donated $250 in 11 days to enable him to report this story. Six months later, investigative proposals on Spot.Us were receiving an average of $750 donated by 35 to 40 supporters.

It seems to be a time-honored journalistic tradition to launch partnerships over beer. So whatever else David Cohn and I might have gone on to do differently, know that some things are still sacred among reporters.

That night, as I heard his Spot.Us idea, I knew I wanted to be involved. Floating around the San Francisco reporting scene, I’d heard plenty of ideas for new Web sites, but they all relied on the same advertising model—Punch-a-Monkey ad sales. Few people were thinking about new business models, particularly one requiring people to donate money to pay reporters to do stories.

So happens that a year before, I talked with a very smart, young engineer who spun some yarns about how corn-based fuels get from Iowa fields to California refineries. He’d convinced me that there was a story in the fragility of the biofuels transportation infrastructure in our state and that ethanol’s role in our state’s energy system could bear deeper examination. At any minute, this engineer said, a derailed train could make the whole enterprise a very difficult proposition.

The story was a little too local for my day job at Wired and a little too technical for San Francisco Magazine. It stuck with me, however, as a story in search of a home. When I’d hear a train whistle or read another overheated story about biofuels, I’d say, “You know, I should write that story.” So I wrote up a quick pitch for Spot.Us, and to my great surprise in 11 days various people had come to the Web site, read my proposal, and decided to fund my story.

People—OK, only other journalists—often ask me, “Did you think about who was funding your story?” Sure, I did. I wanted to thank them by providing the most honest reporting I could. Even if I’d wanted to write what the funders wanted, I don’t think I could have. It would have taken a lot of research just to figure out their angle on biofuels. As I told a Dutch weekly when they interviewed me about it, “There was no John ‘I Love Ethanol’ Smith on the [funders] list.” And besides, this was my story that they’d agreed to fund, and I was the one going to report it. None of my funders contacted me or in any way suggested that I push the story in a given direction.

It’s easy to take potshots at Spot.Us in a vacuum. Wouldn’t it be great if reporters could be paid by unmarked bills falling from the sky? Then we could write about anything we wanted. But there is a monetary system that supports journalists, which can’t be ignored, even though that seems to be the basis for a lot of old-school ethical thought.

Take my day job. Wired is an advertising-supported publication and Wired Science, my particular section, often gets ads purchased by the same companies, Shell and Chevron, mostly. Every day I see their ads next to my stories. Sometimes, the colors of our logo (fortuitously) even match their ads. At the end of the day, I know who pays my salary, and it’s only nominally Conde Nast. But that doesn’t change the responsibility that I have to our readers to report from as close to the locus of truth as I can.

Reporting for Spot.Us, where money directly changes hands, is the same as reporting any story for Wired.com. For Spot.Us, the ethical promise inheres in the transparency of the funding. In traditional reporting, my ethics supposedly remain uncompromised because of the opacity of the firewall between our advertising sales team and me. But that firewall is narrow; it doesn’t take much to peek around and see the inner workings of the machine staring back at me from a set of Shell ads deployed on my stories about climate change.

Granted, with my ethanol story, I had it relatively easy. I only made $250, and the story I was trying to tell wasn’t really about the good or evil of ethanol. It was about how the ethanol system works—illuminating facts about government regulations, the number of unit trains carrying ethanol, and future mandates. This left open further debate about the substance’s merits.

I wasn’t investigating the Oakland police shooting of Oscar Grant, that’s for sure. But the principles that I had to hold close—that journalists and fact finders of all stripes have to hold close—remained the same. Get my boots on the ground and ask people who know. Follow my nose for the truth. Don’t trust everything I’m told. Act in good faith. No matter who paid for what, those who read the product depend on an individual reporter and his or her conscience to report the truth.

If we lose faith that reporters can do that, we’ve got bigger problems than crowdfunded investigative journalism.

Alexis Madrigal reports on energy and science at Wired.com.