“What if the people storming the Capitol on January 6 had been Black?” It’s a question posed by many after the events of January 6, and it prompted newsrooms to contrast how law enforcement handled the largely white, pro-Trump mob with the excessive force deployed against the diverse Black Lives Matter protesters that gathered to peacefully protest George Floyd’s death in D.C. months before.

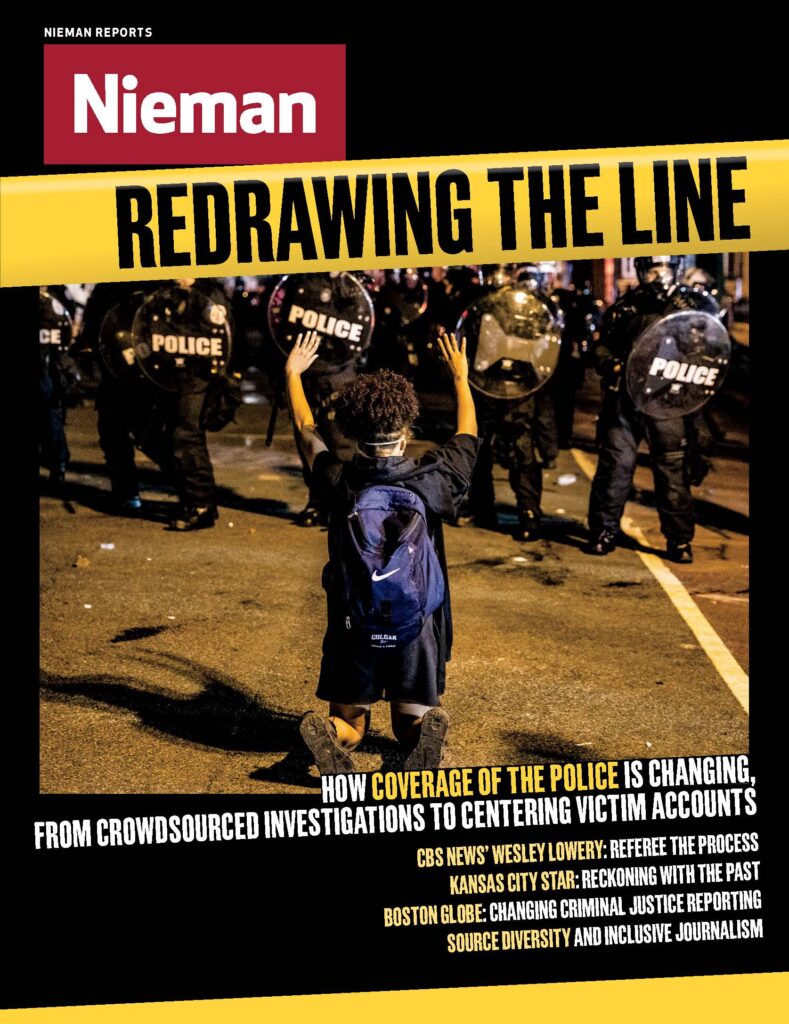

The question is also at the center of examinations of how media coverage of police violence, and of criminal justice, is changing. Spurred in part by Black Lives Matter, a new dynamic is emerging, with news outlets moving away from privileging police accounts over those of police violence victims and their loved ones, taking on interdisciplinary approaches to reporting, and crowdsourcing video investigations of police use of force. This shift is accompanied by other initiatives by newsrooms seeking to acknowledge and address past failures in coverage where race and criminal justice intersect.

Wesley Lowery was just 25 when The Washington Post won a Pulitzer for the newspaper’s “Fatal Force” project in 2016. Lowery was the driving force behind the project, a database of deadly police shootings across the country, which was borne out of his discovery — made while covering several high-profile killings of civilians by police officers in 2014, starting with coverage as the lead reporter in Ferguson, Missouri, following the killing of Michael Brown — that no official statistics on such fatalities existed.

The Post’s former national correspondent covering law enforcement and justice, Lowery joined CBS news in 2020 as a correspondent for “60 Minutes,” and he is also a contributing editor to The Marshall Project. He is the author of “They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement” (Little, Brown and Company, 2016). Lowery spoke with the Nieman Foundation about criminal justice reporting during a February talk. Edited excerpts:

On rethinking criminal justice reporting

I think that one of the biggest biases that we, not just as journalists but as humans, bring to any system or any structure is the assumption that the system in some way works as is.

We’ve seen this play out in a very short and quick timeline with the understanding of policing and police shootings. In 2014, I remember being on the ground in Ferguson, where the kind of consensus establishment wisdom was if the police officer did anything wrong, they’ll charge him with a crime.

We now fast forward what has been six, seven years, and we’ve seen enough cases play out and we’ve done enough reporting where it is clear and obvious that an officer doing something wrong does not, in fact, ensure they will be charged with a crime, much less convicted of a crime, much less fired.

For so long, there was built‑in assumption that the system as is must work. We should let the process play out. What if the process in and of itself is unfair, is biased, doesn’t speak to what should happen?

In some ways, our job as journalists is to monitor and referee not just the people but the process. Our pressure and our interrogation can be something that creates fair or more just processes.

On being too reliant on official sourcing

One thing I think about a lot as someone who’s covered criminal justice and who, with The Boston Globe and the LA Times, previously had been involved in any amount of daily reporting. I was a metro reporter. I was out at the scene. I was in the courthouse figuring out whatever we were going to figure out that day and getting it in the next day’s paper.

Then when I was at The Post, I had the opportunity to be able to look at these issues in a way that, with some exceptions, was very much removed from a daily news cycle.

That’s not to say there were not stories where we needed a piece for tomorrow, but very often my job was, ‘What’s the smartest way to go at this story? How do we take a week and write the piece that makes sense? How do we get answers to all the questions?’

One thing I think about with criminal justice reporting in general is that the vast majority of criminal justice reporting — and frankly most deadline reporting — is done when the least amount of information is available.

If someone is stabbed on my street today, it will be written up and covered in all the D.C. publications. When the person is arrested, maybe it gets a blurb. When the person goes to court, all the details are spread out, but the chances of it actually being written up in any substantive way are almost zero.

When we think about most cases, especially as it relates to crime, as it relates to courts, we do the vast majority of journalism on the least amount of information that’s available.

That, in its nature, results in coverage that is incomplete, that is missing things, missing nuances, missing detail. We are reliant solely on the early reports coming from the system itself, from the police and their early release, from the prosecutor and their early release.

What we know from having covered these institutions is they themselves often will change their story over the course of a case. They will get new information. They will find something new out.

This is very difficult, and I’m very sympathetic and understanding of the position that a lot of reporters working in a daily news cycle are placed in.

The problems are not necessarily with individual reporters but oftentimes the system and the premises of how we are doing this reporting where we are also very reliant on official government sourcing and are reliant on a closeness to that sourcing.

What we know as journalists in any capacity on any beat in any space is that it can be very difficult to maintain critical relationships with people with whom we get that close or for whom our livelihoods are that tied.

In my experience, again, especially more recently, the last six years, not covering policing or criminal justice in a scoop‑driven, daily‑driven way has provided me the ability to step back and have, again, not even adversarial relationships.

I actually, for someone who does a lot of police accountability work, have very good sourcing relationships, spend all day most days talking to cops, and police chiefs, and folks like that, and get tipped to a ton of stuff.

Being able to take that time and take that step back allows a different level of scrutiny to ask the follow‑up question, to say you’re saying this, but this doesn’t actually line up as opposed to a world that is so driven by whatever the police will tell us because that’s what we can get in the paper and that’s going to...That’s a big part of it as well.

Now the secondary question is, ‘Okay, so who are the winners and losers in a process that is so reliant on official sources, on quick‑moving narratives, on lack of follow‑up when details are available?’

In most cases, it’s the people who are at the bottom of the power totem pole as it relates to the criminal justice issues, the people who the police are falsely declaring a suspect, or who prosecutors are over charging. Often we have to walk back what they are doing.

What we know about the way the criminal justice system in America works is that’s going to disproportionately leave Black and brown people being underserved or mis-served by the journalism we’re doing.

The best journalism is done when the most information’s available, when everyone and all the stakeholders in a piece have had an opportunity to speak.

The vast majority of crime pieces or criminal justice coverage, especially, again, in that daily context, so being produced by local television, local papers, local blogs, makes almost no effort whatsoever to reach the suspect, much less victim, of whatever the crime is. It’s almost always power, government, police-driven narrative.

There’s no other context in which we would be OK with that journalistically. I think that’s something that we, as an industry, need to think about.

On abolishing the crime beat

I think there’s a real conversation to be had about, ‘How do we serve the communities we’re supposed to be covering, the nation we’re supposed to be covering, and what is our role? What is the point of doing this type of coverage?’

I think one of the worst reasons to do anything is because this is what we’ve always done. No matter what that is, no matter what that means. I think that when you look at the way we cover crime, and courts, and criminal justice, it’s the heartbeat of what we’ve always done.

I think we’re in an important moment where we can stop, interrogate that a little bit, ask each other our questions, and figure out, ‘What’s the purpose of this work that we’re doing?’

What I also say is that I view the criminal justice beat as a government accountability beat. For the average American, the most powerful person they will ever personally interact with is a police officer. That person has the right to kill them in the street. Donald Trump can’t do that. Joe Biden can’t do that. Hillary Clinton can’t do that. Barack Obama couldn’t do it.

For the average American, the most powerful person they ever interact with is the local police officer. What we know and what we believe as a premise and a value of journalism is that powerful people require watchdogs. They require accountability. We should be asking questions.

A lot of my journalism, and a lot of the ways I think about journalism, are power based. Who are the powerful people in this? Who are the less powerful people in this? How do I calibrate my coverage and my questions so that I’m, in some ways, a voice for the less powerful people, holding accountable the more powerful?

On crime coverage and political divides

Every single study that I know of that’s ever been done on this has found that the average American believes crime is going up and is much worse than it is because [of how] the media presents crime. If a crime occurs, it’s a news story to us.

If we wrote every single day about each homeless person we encountered, the country might have a different perception of how urgent the homelessness issue is, but we don’t. We write about every stabbing, every car robbing, every drunken disorderly. By their very nature, people, when they see something frequently, believe that that frequency is correlated to depth of a problem.

There’s a lot to be said about. Most news organizations cover crime more consistently than any other thing. We don’t write about every climate change study that comes out. We don’t write about everything that the Department of Transportation does.

Cops send us a press release. We’re writing it up. We do need to think in smart ways about what that message that sends to our readers, how that starts to prime them to be concerned about issues of crime and race. What we know is that policing itself is not an objective thing.

If you put the same number of beat cops on Wall Street as you do on Martin Luther King Drive in your city, you’re going to have a bunch of white guys in suits in handcuffs for smoking weed in the corner and for getting drunk in their car, but policing isn’t spread out that way.

What we know is that it’s the majority of people being arrested in a city, or in a municipality, or of a certain demographic, and then our coverage reflects that. That’s going to harden the perception about who might be predisposed to crime, or who’s more dangerous, or who’s more criminal than other folks.

Also in the same way, how we write about every press release we might get from the local PD but maybe not every press release we get from the US Attorney’s Office about a white‑collar thing. [We think,] ‘What is this? This is boring.’ Wait, they arrested a guy in a shooting. Let’s write this. Again, we have to think about what we know demographically about who might be arrested in those things.

On crime coverage and the loss of local journalism

When we did the “Murder with Impunity” project, I was actually surprised by how many murders we looked at. We built a database of 65,000 murders across 60 major cities, and many of these homicides had never been written about once. You could be murdered in a major American city in 2011, and what happened in the case never enters the public record.

My great‑grandfather on my dad’s side was a sharecropper in rural North Carolina, and he had a dispute with the white man who’s land he sharecropped, and the white man murdered him. This is in 1932 I think.

I can read the daily coverage of the trial in the local newspaper. I know more about my great‑grandfather’s murder in the early 1900s than the average murder in Chicago this week. More will have entered the public record about it. I do think that’s a problem.

That speaks to the way we don’t have local journalism the way we used to. The High Country Times that covered my great-grandfather’s murder doesn’t exist anymore in Denver, North Carolina. I do think it’s important for us to be providing coverage.

The thing that is also true though is that our coverage, especially in the Internet age, exists contemporarily in a way that it did not previously. If in the 1970s I went out with my buddies, got a little too drunk, and fought a cop, and ended up spending the night in the drunk tank, my mug shot would appear in the paper, and I’d be really embarrassed.

My mom would have to explain it at church. Two months later, everyone will have forgotten about it. If that happened today, I might never be able to get a job again because the first thing anyone searching for my name would find would be that.

I do think it’s very interesting as newspapers particularly, but also local TV stations and radio stations, are grappling with things like the mugshot galleries that we always published for however long. Now there’s been a big movement away because in a lot of ways, this is purely spectacle. It always was.

It wasn’t that you thought the drunk and disorderly guy was a public‑safety nuance. It was embarrassing and funny, and people were going to pick up the paper to see Joe’s picture from when he got too drunk.

Again, that was significantly more harmless in a time where if you didn’t buy the paper on Tuesday, you’re never going to be able to find it unless you go to the library to search. Sure, if a historian wants to do a paper on drunk and disorderlies in my neighborhood, they can find it. But every employer I ever talk to isn’t going to be ruling me out because of it.

Like all of these issues, these play out demographically about who’s most likely to interact with the criminal justice system and how that then it enforces our perceptions of folks.