August 1999 will mark the 50th anniversary of the Geneva Conventions, the first systematic attempt to establish a legal firebreak between barbarism and civilization in the wake of the Holocaust and the Second World War.

Paradoxically, international humanitarian law based on the Conventions has steadily grown over the last half century, while the scope and number of crimes against humanity have simultaneously increased. “Crimes of War” tells the sobering story of this paradox, defining modern crimes against humanity and recounting the chilling circumstances of their commission.

At the heart of this story is a series of reports. In 145 entries by journalists, lawyers and scholars, Roy Gutman and David Rieff have assembled succinct and devastating accounts of modern genocide, apartheid, collective punishment, disappearances, torture, wanton destruction and other violations of the Geneva Conventions. They have coupled this with methodical descriptions of how these crimes have been committed in Bosnia, Rwanda, South Africa, Colombia, Cambodia, Chechnya and other places in our world. By doing so, they provide an impressive foundation from which editors, reporters, producers and others whose job it becomes to tell these stories can construct accounts that have a basis both in the reality of what they see and the legality of what it means.

Since all human rights work begins with reporting, let me briefly supplement the Gutman-Rieff anthology of war crimes with three accounts from my own experience:

The post-Cold War world was not supposed to turn out this way. Less than a decade ago, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, events appeared to be heading in a very different direction. Changes not expected in this century had transformed the world in a matter of months. Commentators pontificated about “the end of history,” as if the expansion of democracy and universal recognition of human rights were inevitable byproducts of the end of communism. But events in Bosnia, Rwanda and now Kosovo turned these unrealistic hopes into dust. By the mid-1990’s commentators had shifted away from proclaiming the end of history to predicting the advent of global chaos, from the wave of democratization to the clash of civilizations.

RELATED ARTICLE

"9 Mass Graves: An Excerpt From ‘Crimes of War’"

- Elizabeth NeufferWhich will it be? During the last decade there has indeed been a real and measurable trend toward greater global democracy, but the tensions and pressures of globalization have also generated unprecedented upheavals. There are more democracies, but there are also more conflicts. The repressive but relatively stable Cold War system has disappeared, but no other form of international order has yet emerged to take its place. This uncertainty has thrust human rights issues to the forefront and made the protection of them far more complicated. For every Mandela, there is a Milosevic. For every Velvet Revolution, there is a vicious civil war.

Human rights work in the post-Cold War era not only draws upon the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva Conventions; it also requires strategic action to counter the efforts of cynical leaders who manipulate change to instill fear, revive repression and promote genocide.

Today, a whole new set of human rights challenges confront the world, stemming from the growing clash between globalization, on the one hand, and national disintegration, on the other. Countries are engaging with each other in an enormous range of activities that transcend their borders. National economies have become increasingly intertwined. Trade, the environment, security and population issues have become powerful forces for global integration. New technologies of communication, transportation, satellite television and the Internet bring people of different countries and cultures together.

Yet as globalization creates opportunities for economic growth and the flow of ideas and blending of cultures, it also produces powerful reactions in the form of nationalism, religious fundamentalism and political repression. People in the throes of disorienting change (like the breakup of Yugoslavia) seek refuge from an uncertain future in their own national, ethnic or religious identity. Cynical political leaders like Slobodan Milosevic enhance their power by preying on popular insecurities and fanning the flames of communal violence.

In Bosnia, Rwanda, Kosovo and other places described in “Crimes of War,” we have seen where all of this can lead. Genocide or other crimes against humanity can be committed with frightening efficiency and little technology in just a few weeks—as was the case in Rwanda—or over several years, as in the case of the former Yugoslavia. For those who were not slaughtered, there is the misery of the refugee camps and the continuing crises wracking the Balkans and Central Africa. Other post-Cold War conflicts involving war crimes have occurred in Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Haiti, Burma, Afghanistan, Colombia, Liberia, Sudan, Sierra Leone and East Timor, to name just a few from the “Crimes of War” anthology.

Countries in conflict today operate as the human rights equivalents of astronomical black holes, destroying the very moorings of civilization from within and spreading negative influences across entire regions. If these modern conflicts are to be contained and war crimes curtailed, the international community must develop an approach to human rights crises that, in the short run, can limit their negative influence on other countries and, over the long run, can respond to their peoples’ democratic aspirations. This is the challenge implicitly thrown down by the editors of “Crimes of War.”

Three broad strategies are essential if it is to be met: early warning, intervention and justice.

From top to bottom: Victims of the fall of Srebrenica in the mass grave at Pilice Collective Farm; view of the mass grave at Ovcara where the Serbs murdered patients and staff from the hospital in Vukovar; forensic scientists Dr. Clyde Snow and Bill Haglund and their team examine the mass grave at Ovcara. Photos by Gilles Peress/Magnum Photos.

Early Warning

How can we develop better early warning systems to predict the outbreak or recurrence of what happened in Bosnia, Rwanda and Kosovo? During the past five years the international community has begun to institutionalize the use of human rights and refugee missions as early warning mechanisms. The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as the human rights field operations of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), have established early warning systems in dozens of potential conflict areas.

In East-Central Europe, the OSCE High Commissioner for National Minorities and the Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights have played a similar role, and in Latin America the Organization of American States (OAS) is increasingly a regional resource for early warning and conflict prevention.

Once forewarned of a potential conflict involving human rights crimes, preventive action can be mounted in a number of forms. Measures such as visa and arms restriction and the conditioning of access to international financing and bilateral assistance can be used to put pressure on leaders who are promoting conflict. At times, mediation can be brought to bear on the crisis. In Guatemala and El Salvador the United Nations and the OAS negotiated an end to conflicts involving massive human rights abuses. Behind-the-scenes mediation often goes unreported. In Estonia, for example, the OSCE quietly sponsored a series of local open forums on minority rights in 1993 and 1994 that brought together Estonians and Russians and effectively defused the explosive potential for violence.

Intervention

When early warning fails, more active measures such as economic sanctions may become necessary, especially when a large portion of the population is threatened by violations of international humanitarian law. But sanctions are most effective when they are broadly multilateral—for example, when they were aimed against the apartheid regime of South Africa—and that kind of success is difficult to achieve.

A more effective mechanism than sanctions can be the creation of a coalition of states to take collective action in response to massive human rights abuses. The larger the number of countries involved in this kind of intervention, the greater its legitimacy and potential for success. In Haiti, for example, the United States worked with the United Nations, the OAS and regional leaders to respond to the violent overthrow of a democratic government and an ongoing systematic pattern of human rights abuses. In Mozambique and Namibia, United Nations and African leaders backed by an international coalition brokered the settlement of violent conflicts and the transition to democracy.

But these success stories are overshadowed by the failure of early interventions in Bosnia and Rwanda. A lesson of these failures is that traditional peacekeeping with its limited rules of engagement is inadequate and sometimes even counterproductive when a conflict at its very root involves crimes against humanity.

That lesson is powerfully recounted in the chapters on Bosnia and Rwanda in “Crimes of War.” Beyond the inability of traditional peacekeeping to respond to modern war crimes, it is also true, as Gutman and Rieff graphically illustrate, that outmoded interpretations of the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states has inhibited international efforts to address these situations. As the Kosovo crisis also demonstrates, national sovereignty can no longer be permitted to shield crimes against humanity from international scrutiny and response.

The events in Rwanda, Bosnia and Kosovo have clear repercussions for international security. The failure of early peacekeeping efforts in these situations reflected a reluctance by the international community to use force as a last resort in response to massive violations of international humanitarian law. By contrast, the multinational force that entered Haiti in October 1994, the NATO force that was deployed in Bosnia to implement the Dayton Accords in November 1995, and the NATO air strikes on Serbia that began in March 1999 were all authorized to respond directly to massive human rights abuses. The decisions of the international community to intervene in Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo signal what could be the beginning of a fundamentally different approach to addressing crimes against humanity—an approach that draws its legitimacy and mandate from the international humanitarian law summarized in “Crimes of War.”

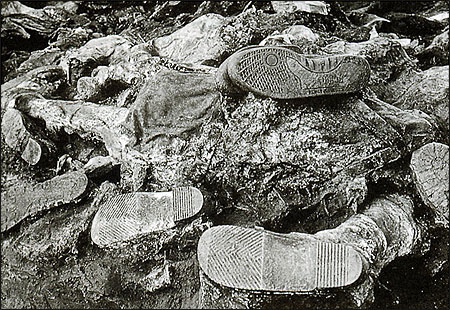

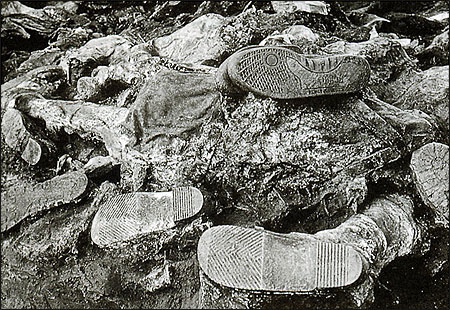

Skeletal remains of bodies exhumed from a mass grave in Sanski Most, Bosnia, in March 1999. Photo by Radivoje Pavicic, courtesy of The Boston Globe.

Justice

Another lesson of Bosnia, Rwanda and Kosovo is that conflicts involving genocide or crimes against humanity cannot be resolved without the involvement of institutions of justice. Revenge may offer the victims fleeting satisfaction, but only at the cost of a perpetual violent cycle of hate. Justice can offer survivors an opportunity to right the wrongs committed against them by holding accountable those who were responsible. Justice can be equally important to innocent members of national or ethnic groups involved in the conflict because it can help remove the stigma of guilt by association that settles over an entire group when some of its members have committed war crimes. Justice can also serve as a warning to others who might want to engage in similar acts in the future.

For all these reasons the International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda are essential to the resolution of conflicts involving crimes against humanity. As Gutman and Rieff point out, the international community must help these tribunals to function as key elements of an evolving global response to war crimes—for example, by facilitating the arrest of indicted war criminals. What makes the two tribunals remarkable is that they are charting completely new territory in international law. Not even the Nuremburg trials involved bringing justice to an ongoing conflict as a means of ending it, and certainly no other international institution of justice has ever tried to do so.

Of course, international justice by itself is not enough. Over the long run, the only way to deter war crimes is to build indigenous national institutions that foster the rule of law in countries that are emerging from conflict. Truth Commissions in South Africa, El Salvador and elsewhere have played a critical role in uncovering and rectifying human rights crimes. National courts must also play their role, as can national human rights commissions. For this reason international donor countries are now programming substantial amounts of foreign aid to support the rule of law in post-conflict and transitional countries. This aid is used, for example, to support the training of judges, court administrators, prosecutors, defense lawyers and the police. It also provides assistance for legal education and the writing of constitutions and a wide range of other law reform activities designed to create new institutions of domestic justice and human rights enforcement.

As the bloodiest century in history comes to a close, it is imperative that the promise of the Geneva Conventions be fulfilled. To do so we need a better understanding of modern war crimes and a stronger commitment to the evolving strategy for addressing them. “Crimes of War” is a solid contribution to the former and a provocative inspiration for the latter.

John Shattuck is United States Ambassador to the Czech Republic and former Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 1993-98. He and Hume have been married since 1991.

Paradoxically, international humanitarian law based on the Conventions has steadily grown over the last half century, while the scope and number of crimes against humanity have simultaneously increased. “Crimes of War” tells the sobering story of this paradox, defining modern crimes against humanity and recounting the chilling circumstances of their commission.

At the heart of this story is a series of reports. In 145 entries by journalists, lawyers and scholars, Roy Gutman and David Rieff have assembled succinct and devastating accounts of modern genocide, apartheid, collective punishment, disappearances, torture, wanton destruction and other violations of the Geneva Conventions. They have coupled this with methodical descriptions of how these crimes have been committed in Bosnia, Rwanda, South Africa, Colombia, Cambodia, Chechnya and other places in our world. By doing so, they provide an impressive foundation from which editors, reporters, producers and others whose job it becomes to tell these stories can construct accounts that have a basis both in the reality of what they see and the legality of what it means.

Since all human rights work begins with reporting, let me briefly supplement the Gutman-Rieff anthology of war crimes with three accounts from my own experience:

- In May 1994, President Clinton sent me to Central Africa to meet on an urgent basis with regional leaders about the massive killings then going on in Rwanda. As I flew over the Rwanda-Tanzania border in a small plane, I saw what looked like logs floating down the Kagera River. Flying lower, I realized that the river was choked with corpses, the product of a ghastly campaign of genocide.

- A year later, in July 1995, I traveled to the then-isolated Bosnian town of Tuzla to interview refugees streaming in from Srebenica. I had gone to investigate reports of atrocities. What I learned was staggering. The survivors, including three men who had escaped their own executions, recounted to me in graphic detail the torture and cold-blooded murder of thousands of unarmed Muslim men by General Ratko Mladic and his Serb troops. Srebenica would prove to be the largest single act of genocide in Europe since the Second World War.

- In September 1998 I went on a fact-finding trip to Kosovo with former Senator Bob Dole. Our mission was to interview internally displaced persons to find out why more than 250,000 Kosovars had fled their homes. We heard and reported accounts of the systematic shelling of Kosovar villages and unarmed refugees by Serb paramilitary forces and the rounding up and execution of military-aged men—part of the ongoing campaign by Serb President Slobodan Milosevic to terrorize and drive away the Kosovar population.

The post-Cold War world was not supposed to turn out this way. Less than a decade ago, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, events appeared to be heading in a very different direction. Changes not expected in this century had transformed the world in a matter of months. Commentators pontificated about “the end of history,” as if the expansion of democracy and universal recognition of human rights were inevitable byproducts of the end of communism. But events in Bosnia, Rwanda and now Kosovo turned these unrealistic hopes into dust. By the mid-1990’s commentators had shifted away from proclaiming the end of history to predicting the advent of global chaos, from the wave of democratization to the clash of civilizations.

RELATED ARTICLE

"9 Mass Graves: An Excerpt From ‘Crimes of War’"

- Elizabeth NeufferWhich will it be? During the last decade there has indeed been a real and measurable trend toward greater global democracy, but the tensions and pressures of globalization have also generated unprecedented upheavals. There are more democracies, but there are also more conflicts. The repressive but relatively stable Cold War system has disappeared, but no other form of international order has yet emerged to take its place. This uncertainty has thrust human rights issues to the forefront and made the protection of them far more complicated. For every Mandela, there is a Milosevic. For every Velvet Revolution, there is a vicious civil war.

Human rights work in the post-Cold War era not only draws upon the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva Conventions; it also requires strategic action to counter the efforts of cynical leaders who manipulate change to instill fear, revive repression and promote genocide.

Today, a whole new set of human rights challenges confront the world, stemming from the growing clash between globalization, on the one hand, and national disintegration, on the other. Countries are engaging with each other in an enormous range of activities that transcend their borders. National economies have become increasingly intertwined. Trade, the environment, security and population issues have become powerful forces for global integration. New technologies of communication, transportation, satellite television and the Internet bring people of different countries and cultures together.

Yet as globalization creates opportunities for economic growth and the flow of ideas and blending of cultures, it also produces powerful reactions in the form of nationalism, religious fundamentalism and political repression. People in the throes of disorienting change (like the breakup of Yugoslavia) seek refuge from an uncertain future in their own national, ethnic or religious identity. Cynical political leaders like Slobodan Milosevic enhance their power by preying on popular insecurities and fanning the flames of communal violence.

In Bosnia, Rwanda, Kosovo and other places described in “Crimes of War,” we have seen where all of this can lead. Genocide or other crimes against humanity can be committed with frightening efficiency and little technology in just a few weeks—as was the case in Rwanda—or over several years, as in the case of the former Yugoslavia. For those who were not slaughtered, there is the misery of the refugee camps and the continuing crises wracking the Balkans and Central Africa. Other post-Cold War conflicts involving war crimes have occurred in Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Haiti, Burma, Afghanistan, Colombia, Liberia, Sudan, Sierra Leone and East Timor, to name just a few from the “Crimes of War” anthology.

Countries in conflict today operate as the human rights equivalents of astronomical black holes, destroying the very moorings of civilization from within and spreading negative influences across entire regions. If these modern conflicts are to be contained and war crimes curtailed, the international community must develop an approach to human rights crises that, in the short run, can limit their negative influence on other countries and, over the long run, can respond to their peoples’ democratic aspirations. This is the challenge implicitly thrown down by the editors of “Crimes of War.”

Three broad strategies are essential if it is to be met: early warning, intervention and justice.

From top to bottom: Victims of the fall of Srebrenica in the mass grave at Pilice Collective Farm; view of the mass grave at Ovcara where the Serbs murdered patients and staff from the hospital in Vukovar; forensic scientists Dr. Clyde Snow and Bill Haglund and their team examine the mass grave at Ovcara. Photos by Gilles Peress/Magnum Photos.

Early Warning

How can we develop better early warning systems to predict the outbreak or recurrence of what happened in Bosnia, Rwanda and Kosovo? During the past five years the international community has begun to institutionalize the use of human rights and refugee missions as early warning mechanisms. The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as the human rights field operations of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), have established early warning systems in dozens of potential conflict areas.

In East-Central Europe, the OSCE High Commissioner for National Minorities and the Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights have played a similar role, and in Latin America the Organization of American States (OAS) is increasingly a regional resource for early warning and conflict prevention.

Once forewarned of a potential conflict involving human rights crimes, preventive action can be mounted in a number of forms. Measures such as visa and arms restriction and the conditioning of access to international financing and bilateral assistance can be used to put pressure on leaders who are promoting conflict. At times, mediation can be brought to bear on the crisis. In Guatemala and El Salvador the United Nations and the OAS negotiated an end to conflicts involving massive human rights abuses. Behind-the-scenes mediation often goes unreported. In Estonia, for example, the OSCE quietly sponsored a series of local open forums on minority rights in 1993 and 1994 that brought together Estonians and Russians and effectively defused the explosive potential for violence.

Intervention

When early warning fails, more active measures such as economic sanctions may become necessary, especially when a large portion of the population is threatened by violations of international humanitarian law. But sanctions are most effective when they are broadly multilateral—for example, when they were aimed against the apartheid regime of South Africa—and that kind of success is difficult to achieve.

A more effective mechanism than sanctions can be the creation of a coalition of states to take collective action in response to massive human rights abuses. The larger the number of countries involved in this kind of intervention, the greater its legitimacy and potential for success. In Haiti, for example, the United States worked with the United Nations, the OAS and regional leaders to respond to the violent overthrow of a democratic government and an ongoing systematic pattern of human rights abuses. In Mozambique and Namibia, United Nations and African leaders backed by an international coalition brokered the settlement of violent conflicts and the transition to democracy.

But these success stories are overshadowed by the failure of early interventions in Bosnia and Rwanda. A lesson of these failures is that traditional peacekeeping with its limited rules of engagement is inadequate and sometimes even counterproductive when a conflict at its very root involves crimes against humanity.

That lesson is powerfully recounted in the chapters on Bosnia and Rwanda in “Crimes of War.” Beyond the inability of traditional peacekeeping to respond to modern war crimes, it is also true, as Gutman and Rieff graphically illustrate, that outmoded interpretations of the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states has inhibited international efforts to address these situations. As the Kosovo crisis also demonstrates, national sovereignty can no longer be permitted to shield crimes against humanity from international scrutiny and response.

The events in Rwanda, Bosnia and Kosovo have clear repercussions for international security. The failure of early peacekeeping efforts in these situations reflected a reluctance by the international community to use force as a last resort in response to massive violations of international humanitarian law. By contrast, the multinational force that entered Haiti in October 1994, the NATO force that was deployed in Bosnia to implement the Dayton Accords in November 1995, and the NATO air strikes on Serbia that began in March 1999 were all authorized to respond directly to massive human rights abuses. The decisions of the international community to intervene in Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo signal what could be the beginning of a fundamentally different approach to addressing crimes against humanity—an approach that draws its legitimacy and mandate from the international humanitarian law summarized in “Crimes of War.”

Skeletal remains of bodies exhumed from a mass grave in Sanski Most, Bosnia, in March 1999. Photo by Radivoje Pavicic, courtesy of The Boston Globe.

Justice

Another lesson of Bosnia, Rwanda and Kosovo is that conflicts involving genocide or crimes against humanity cannot be resolved without the involvement of institutions of justice. Revenge may offer the victims fleeting satisfaction, but only at the cost of a perpetual violent cycle of hate. Justice can offer survivors an opportunity to right the wrongs committed against them by holding accountable those who were responsible. Justice can be equally important to innocent members of national or ethnic groups involved in the conflict because it can help remove the stigma of guilt by association that settles over an entire group when some of its members have committed war crimes. Justice can also serve as a warning to others who might want to engage in similar acts in the future.

For all these reasons the International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda are essential to the resolution of conflicts involving crimes against humanity. As Gutman and Rieff point out, the international community must help these tribunals to function as key elements of an evolving global response to war crimes—for example, by facilitating the arrest of indicted war criminals. What makes the two tribunals remarkable is that they are charting completely new territory in international law. Not even the Nuremburg trials involved bringing justice to an ongoing conflict as a means of ending it, and certainly no other international institution of justice has ever tried to do so.

Of course, international justice by itself is not enough. Over the long run, the only way to deter war crimes is to build indigenous national institutions that foster the rule of law in countries that are emerging from conflict. Truth Commissions in South Africa, El Salvador and elsewhere have played a critical role in uncovering and rectifying human rights crimes. National courts must also play their role, as can national human rights commissions. For this reason international donor countries are now programming substantial amounts of foreign aid to support the rule of law in post-conflict and transitional countries. This aid is used, for example, to support the training of judges, court administrators, prosecutors, defense lawyers and the police. It also provides assistance for legal education and the writing of constitutions and a wide range of other law reform activities designed to create new institutions of domestic justice and human rights enforcement.

As the bloodiest century in history comes to a close, it is imperative that the promise of the Geneva Conventions be fulfilled. To do so we need a better understanding of modern war crimes and a stronger commitment to the evolving strategy for addressing them. “Crimes of War” is a solid contribution to the former and a provocative inspiration for the latter.

John Shattuck is United States Ambassador to the Czech Republic and former Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 1993-98. He and Hume have been married since 1991.