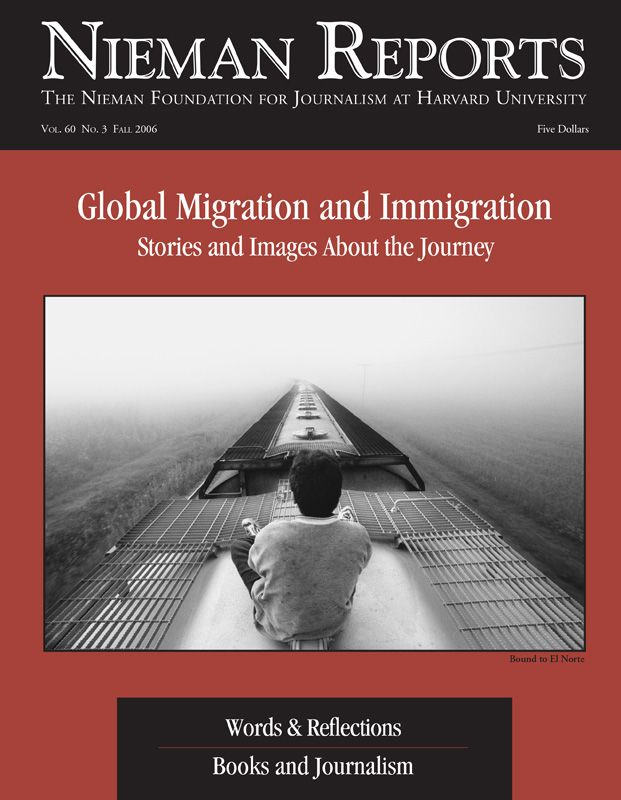

Global Migration and Immigration: Stories and Images About the Journey

When I was a border correspondent, I learned to move between both sides, quickly and frequently, physically and mentally, while striving for balance. I learned to maneuver in gray areas. And I learned there was no substitute for being out in the field, on the street, at the line — talking with migrants and cops and desperados, the gatekeepers of the secret worlds.

China is in the midst of the biggest and fastest rural to urban migration in human history. During the next two decades, the Chinese government expects more than 300 million Chinese to move from villages to cities. To make that possible, it plans to build the equivalent of a new Shanghai — population approaching 20 million — every year.

Meanwhile, well over 100 million Chinese have already tossed aside their plows to look for work and a better life in the city — but not as bona fide urban residents, with all the government-issued rights that go with that status. Instead, they reside in the sometimes dangerous, always difficult netherworld of migrant labor.

For years, migrant workers have filled the assembly-line jobs in China's factories and constructed its gleaming new buildings — taking home as little as $60 to $100 a month, when they're lucky enough to get paid at all. They live in cramped and dingy dwellings, sometimes little more than a shack under a highway interchange. Their children are often turned away from attending urban schools, and the makeshift ones migrants create are regularly shut down by local authorities who claim that they do not meet official standards.

Such treatment has long been central to the government's strategy to not let migrant families get too comfortable, lest they decide to stay. Until recently, they've been treated in the state-run media — and in their lives — as a necessary, if somewhat grubby, embarrassment to the more sophisticated urban citizenry.

The Media and Migrants

When I was based in China a decade ago for NPR, I remember seeing only a few stories on migrant workers in the official Chinese media that didn't focus on some aspect of their general nuisance value or illegality. That "illegality" relates to a largely outdated "hukou," or residence permit, system that requires most people to stay where they were born if they want access to such government-subsidized services as education and health care. This accepted practice created an unofficial class system with those who were born in the country's big cities receiving more and better services and subsidies. That, by itself, used to provide ample incentive for migrant workers to flock to cities in search of better lives and ample reason for city-dwellers and the state-run media to look on disapprovingly.

But times are changing, and so is Chinese news media coverage of migrant worker issues. As China has transformed from socialism to a free(r) market, government-supplied services have diminished dramatically, and Chinese, both rural and urban, have begun to see mobility as their right. And a new attitude toward migrant workers has begun to emerge in the Chinese news media.

In June, The Beijing Times published an article examining unsafe work conditions for construction workers, and that same month the China Daily shared with readers news that migrant workers have contributed 16 percent of China's gross domestic product (GDP) growth over the past 20 years, according to a new report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A Worker's Daily commentary called for an end to discrimination of migrant workers. And the state's official broadcaster, CCTV (China Central Television), aired a long piece about migrant workers who were trying, to no avail, to collect their back pay. On the CCTV Web site, viewers responded with such comments as: "I was crying when I was watching that program. It is so sad," and "I hate those bastards who cheat migrant workers. They are worse than animals."

Why has there been this shift in attitude? In part, it can be traced to the fact that while China's news media are still state-controlled, most operate on a commercial basis and compete with each other for readers, viewers and listeners — and they do this by chasing after compelling stories about such human injustice. Because such stories are now being done, a generation of young Chinese journalists is developing an appetite for telling them.

But such explanations would not suffice if the Chinese government were not leading by example. It has pledged to eventually abolish the hukou system and to protect the rights of migrant workers — including their right to be compensated for the work they do. In a news conference two years ago, China's then-minister of labor and social security, Zheng Silin, announced somewhat sheepishly that the government had just paid out the equivalent of four billion dollars in back pay to migrant workers who'd been stiffed by state-owned enterprises. Some of these payments, he admitted, were for work done 10 years earlier.

Frustration over such worker exploitation and general ill-treatment of migrants is one of the reasons why the number of protests around China has grown dramatically of late — to 87,000 last year, according to Chinese police records. Many of the protests were about the corruption of government officials or their land grabs, but migrant workers protested, too, about not being paid or about the abuse they've endured from employers. Just this summer, hundreds of protesters in the southern province of Guizhou overturned police vehicles and threw bricks after people hired by police beat up a migrant worker until blood was streaming down his face because he didn't have a resident's permit for the city he was in and refused to pay for one.

International Connection

This story about the beat-up migrant worker first appeared in the state-run Guizhou Metropolitan News. From there, it got picked up by The Associated Press and other international news media. And this is becoming a familiar pattern: As the Chinese news media — particularly local media — become more enterprising and daring, they are seen increasingly as an effective alert for international news media who are interested in reporting on the same issues.

But not always. Enterprising and daring though some of China's news media may be, they are still state-run. And during the past couple of years, the state has imposed a chill on the press. The government has shut down publications and jailed editors who were too daring and issued regulations that forbid sensitive subjects from being covered by state-run media. State and party media officials update prohibitions on an almost daily basis, sometimes by sending text messages to reporters' mobile phones.

In such an environment, foreign correspondents can and have helped push such stories into prominence, sometimes after getting quiet tips from their Chinese counterparts. But now, the Chinese government is considering new legislation that could result in both Chinese and foreign journalists being fined up to $12,500 each time they cover "unexpected news" — breaking stories — without first getting permission from the relevant local authorities. In other words, the next time a foreign correspondent happens to be in a city when a riot starts because a migrant worker has been beaten to a pulp by police, the journalist is supposed to get permission from the police to do the story. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China is lobbying for the proposed legislation to be dropped.

Meanwhile, migrant workers are finding their own way for their voices to be heard — not just through protests but also by the absence of workers themselves. Factories in southern China — where much of the world's inexpensive clothes and toys are made — are hundreds of thousands of workers short. As China's one-child-per-family generation moves into adulthood, there just aren't as many people willing to move far from home to work long hours under often dangerous conditions for dirt-cheap wages they might not ever receive. Some are staying on the farm, where the government's cancellation of rural tax is making farming more profitable. Others work at factories that are now being built closer to them. Still others are becoming better educated and finding better paying jobs.

Members of China's news media are increasingly following this evolution with sympathy and nuance — echoing the government's new "equal rights for migrant workers" line, but also pointing out when migrant workers' harsh treatment by local officials doesn't match that lofty rhetoric. For international journalists, such reporting is business as usual. But for Chinese journalists — who work for news organizations owned and overseen by a government not used to being challenged — the cumulative effect of their pushing-the-edge reporting on migrants and other issues is creating a little revolution all its own.

Mary Kay Magistad, a 2000 Nieman Fellow, is the Beijing-based Northeast Asia correspondent for the Public Radio International/BBC/WGBH program "The World."

Meanwhile, well over 100 million Chinese have already tossed aside their plows to look for work and a better life in the city — but not as bona fide urban residents, with all the government-issued rights that go with that status. Instead, they reside in the sometimes dangerous, always difficult netherworld of migrant labor.

For years, migrant workers have filled the assembly-line jobs in China's factories and constructed its gleaming new buildings — taking home as little as $60 to $100 a month, when they're lucky enough to get paid at all. They live in cramped and dingy dwellings, sometimes little more than a shack under a highway interchange. Their children are often turned away from attending urban schools, and the makeshift ones migrants create are regularly shut down by local authorities who claim that they do not meet official standards.

Such treatment has long been central to the government's strategy to not let migrant families get too comfortable, lest they decide to stay. Until recently, they've been treated in the state-run media — and in their lives — as a necessary, if somewhat grubby, embarrassment to the more sophisticated urban citizenry.

The Media and Migrants

When I was based in China a decade ago for NPR, I remember seeing only a few stories on migrant workers in the official Chinese media that didn't focus on some aspect of their general nuisance value or illegality. That "illegality" relates to a largely outdated "hukou," or residence permit, system that requires most people to stay where they were born if they want access to such government-subsidized services as education and health care. This accepted practice created an unofficial class system with those who were born in the country's big cities receiving more and better services and subsidies. That, by itself, used to provide ample incentive for migrant workers to flock to cities in search of better lives and ample reason for city-dwellers and the state-run media to look on disapprovingly.

But times are changing, and so is Chinese news media coverage of migrant worker issues. As China has transformed from socialism to a free(r) market, government-supplied services have diminished dramatically, and Chinese, both rural and urban, have begun to see mobility as their right. And a new attitude toward migrant workers has begun to emerge in the Chinese news media.

In June, The Beijing Times published an article examining unsafe work conditions for construction workers, and that same month the China Daily shared with readers news that migrant workers have contributed 16 percent of China's gross domestic product (GDP) growth over the past 20 years, according to a new report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A Worker's Daily commentary called for an end to discrimination of migrant workers. And the state's official broadcaster, CCTV (China Central Television), aired a long piece about migrant workers who were trying, to no avail, to collect their back pay. On the CCTV Web site, viewers responded with such comments as: "I was crying when I was watching that program. It is so sad," and "I hate those bastards who cheat migrant workers. They are worse than animals."

Why has there been this shift in attitude? In part, it can be traced to the fact that while China's news media are still state-controlled, most operate on a commercial basis and compete with each other for readers, viewers and listeners — and they do this by chasing after compelling stories about such human injustice. Because such stories are now being done, a generation of young Chinese journalists is developing an appetite for telling them.

But such explanations would not suffice if the Chinese government were not leading by example. It has pledged to eventually abolish the hukou system and to protect the rights of migrant workers — including their right to be compensated for the work they do. In a news conference two years ago, China's then-minister of labor and social security, Zheng Silin, announced somewhat sheepishly that the government had just paid out the equivalent of four billion dollars in back pay to migrant workers who'd been stiffed by state-owned enterprises. Some of these payments, he admitted, were for work done 10 years earlier.

Frustration over such worker exploitation and general ill-treatment of migrants is one of the reasons why the number of protests around China has grown dramatically of late — to 87,000 last year, according to Chinese police records. Many of the protests were about the corruption of government officials or their land grabs, but migrant workers protested, too, about not being paid or about the abuse they've endured from employers. Just this summer, hundreds of protesters in the southern province of Guizhou overturned police vehicles and threw bricks after people hired by police beat up a migrant worker until blood was streaming down his face because he didn't have a resident's permit for the city he was in and refused to pay for one.

International Connection

This story about the beat-up migrant worker first appeared in the state-run Guizhou Metropolitan News. From there, it got picked up by The Associated Press and other international news media. And this is becoming a familiar pattern: As the Chinese news media — particularly local media — become more enterprising and daring, they are seen increasingly as an effective alert for international news media who are interested in reporting on the same issues.

But not always. Enterprising and daring though some of China's news media may be, they are still state-run. And during the past couple of years, the state has imposed a chill on the press. The government has shut down publications and jailed editors who were too daring and issued regulations that forbid sensitive subjects from being covered by state-run media. State and party media officials update prohibitions on an almost daily basis, sometimes by sending text messages to reporters' mobile phones.

In such an environment, foreign correspondents can and have helped push such stories into prominence, sometimes after getting quiet tips from their Chinese counterparts. But now, the Chinese government is considering new legislation that could result in both Chinese and foreign journalists being fined up to $12,500 each time they cover "unexpected news" — breaking stories — without first getting permission from the relevant local authorities. In other words, the next time a foreign correspondent happens to be in a city when a riot starts because a migrant worker has been beaten to a pulp by police, the journalist is supposed to get permission from the police to do the story. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China is lobbying for the proposed legislation to be dropped.

Meanwhile, migrant workers are finding their own way for their voices to be heard — not just through protests but also by the absence of workers themselves. Factories in southern China — where much of the world's inexpensive clothes and toys are made — are hundreds of thousands of workers short. As China's one-child-per-family generation moves into adulthood, there just aren't as many people willing to move far from home to work long hours under often dangerous conditions for dirt-cheap wages they might not ever receive. Some are staying on the farm, where the government's cancellation of rural tax is making farming more profitable. Others work at factories that are now being built closer to them. Still others are becoming better educated and finding better paying jobs.

Members of China's news media are increasingly following this evolution with sympathy and nuance — echoing the government's new "equal rights for migrant workers" line, but also pointing out when migrant workers' harsh treatment by local officials doesn't match that lofty rhetoric. For international journalists, such reporting is business as usual. But for Chinese journalists — who work for news organizations owned and overseen by a government not used to being challenged — the cumulative effect of their pushing-the-edge reporting on migrants and other issues is creating a little revolution all its own.

Mary Kay Magistad, a 2000 Nieman Fellow, is the Beijing-based Northeast Asia correspondent for the Public Radio International/BBC/WGBH program "The World."