Translated by Anne Henochowicz

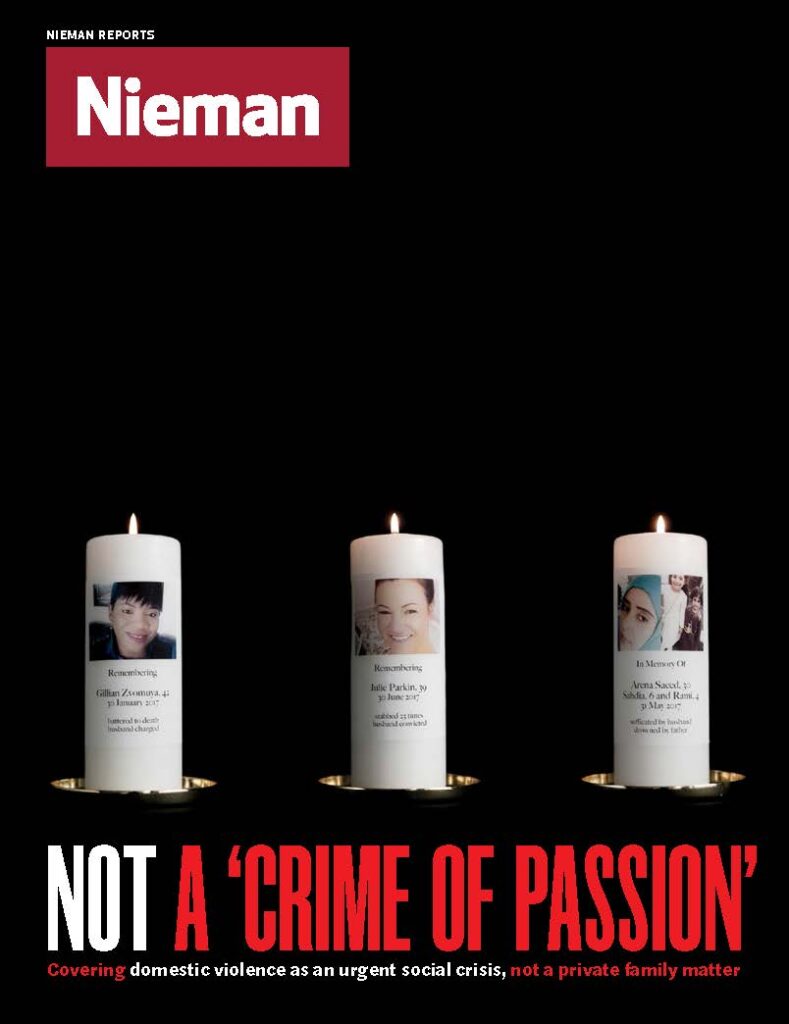

On February 19, 2013, when lawyer Guo Jianmei was on a business trip, her phone rang. The moment had arrived for the review of Li Yan’s death sentence.

Li Yan, a woman from Anyue County in Sichuan Province, was the defendant in a case of intentional homicide. On November 3, 2010, while defending herself against her husband’s extreme abuse, she killed him, then dismembered his corpse. She was given a death sentence at her second trial in August 2012. From there, her case went to the Supreme People’s Court for review. Li’s lawyers, including Guo, argued that domestic violence had driven Li to commit the crime, and that she did not deserve the death penalty.

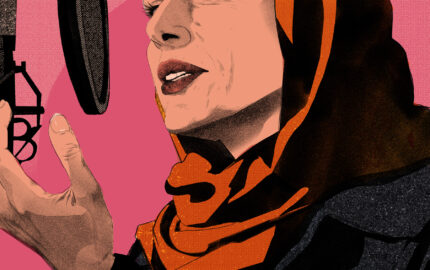

Guo decided to follow the American justice model and use Li’s case to push for a national law on domestic violence. She called a reporter, in the hope that the media would speak up for Li. As a public interest lawyer, Guo had a list of journalists with whom she often worked. Guo also notified a number of NGOs, hoping to ignite public discussion of the case.

Her plan worked. The intense media coverage educated the public about domestic violence. The effect was substantive as well, as public opinion exerted pressure on the high court. In the end, Guo saved Li’s life—while Li was given the death penalty, her sentence was suspended for two years. She was told that her sentence would be commuted to life with the possibility of parole if she didn’t commit a crime during that period. She remains in prison.

When China’s Domestic Violence Law was drafted in 2013, Li’s case pushed the bill into public view. At the time, Guo’s law center had ample funding from a number of grants, and many of the lawyers there were working on domestic violence cases.

Despite China’s progress, the national climate has impeded action on domestic violence

In 2016, China finally passed its Domestic Violence Law, which took effect in March of that year. The law stipulates that the injuring party’s act of domestic violence constitutes a civil infraction, not a criminal offense.

At least one in four married women in China has experienced intimate partner violence. According to a 2015 report by the Supreme People’s Court, nearly 10 percent of intentional homicide cases involve domestic violence. But for a long time, government employees, both lawyers and judges, have had little understanding of domestic violence. The new law has helped to make them more aware of the issue.

Guo believes the Domestic Violence Law stands as the greatest advancement for women’s rights in China. The issue could easily have been ignored because it has little to do with national politics or the economy.

Two years after the new law went into effect, Equality, a Beijing-based women’s rights organization, in its report on media coverage, found 533 cases of domestic violence homicide in China in the roughly 600 days between March 1, 2016 and October 31, 2017, leading to the deaths of at least 635 adults and children, including neighbors and passersby. There was on average more than one domestic violence homicide every day during that period, and the great majority of victims were women.

In a survey of media coverage of over 300 cases of domestic violence, 249 cases occurred in urban areas, comprising 81.9 percent of the total sample; while 55 rural cases were covered, comprising 18.1 percent. This highlights the media’s focus on urban domestic violence, while incidents in rural areas are overlooked.

It is also hard to find official media coverage of particularly vulnerable groups, such as ethnic minorities, people with serious illnesses, people with disabilities, and sexual minorities. Coverage about the particular demands of combating domestic violence is also lacking.

Despite China’s progress, the national climate has impeded action on domestic violence. According to the Equality report, support for civil society organizations (CSOs) is lacking at all levels of government, and the growth of such organizations has plummeted over the past two years. There are a scant number of anti-domestic violence CSOs, scattered across Beijing and the provinces of Guangdong, Yunnan, Shaanxi, and Hunan. It is difficult for grassroots organizations to obtain legal status as NGOs, and supportive government policies are particularly lacking. Guo’s firm has also been affected by the political climate and funding has dried up.

Li’s 2013 case stands as the most influential in China’s movement to end domestic violence. The combined efforts of public interest law, the media, and NGOs have not had another major breakthrough since.