21st Century Muckrakers: Staying Local, Digging Deep

On this point, editors, reporters and newspaper readers agree. In a time of cutbacks and a shrinking news hole, at a moment when print is in peril and digital is dominant, watchdog and investigative reporting must remain at the core of journalism’s mission. In this third part of our 21st Century Muckrakers project, editors and reporters speak to how metro and regional newspapers are confronting the enormous challenges of today and offer clues to where this kind of reporting will likely be headed tomorrow.

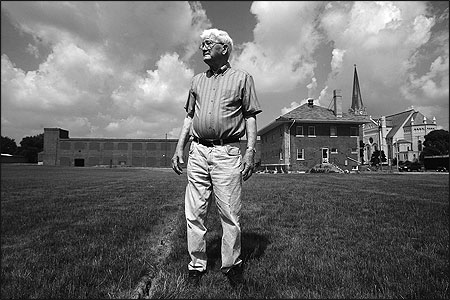

Four days after Christmas in December 2001, National Machinery Company workers read in disbelief the headlines in their local newspaper that their factory, a cornerstone of Tiffin, Ohio, abruptly closed. More than 500 men and women—many who served the company for 25 years or more and some who were second and third generation employees—lost their jobs without any notice. For more than 130 years, the employees there had built the machines that cut nuts and bolts. With its deeply rooted traditions like its summer picnics and its Quarter Century Club for its longest-serving employees, the workers of Tiffin felt honored to serve “The National,” as they affectionately called it.

The manner in which they learned of National’s shuttering left the workers stunned and feeling betrayed. Looking for answers and a way to channel their furor, some learned that National Machinery might have violated the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act, known as the WARN Act, by failing to notify workers of the impending layoffs. The 20-year-old law requires many employers to give workers 60 days advance notice before plant closings and massive layoffs.

Workers later sued, seeking 60 days of back pay, the most they could demand under a WARN Act claim. Three years later and over the objections of former National Machinery employees, U.S. District Court Judge James Carr reluctantly approved a settlement that paid the workers $375 each, a far cry from what many felt they were owed. The judge labeled the settlement a “pittance” and explained that it was the best they could hope for under the weak WARN Act.

Needing a Public Watchdog

Spurned once by his longtime employer and again by the government’s failure to protect workers on the verge of losing their jobs, Tom Kummerer, a National employee for nearly 25 years, called The Blade in nearby Toledo and spoke with Special Assignments Editor Dave Murray. He pleaded for the paper to do some digging, and this became my first investigative project with The Blade.

In July 2007, nearly three years later, The Blade revealed in a four-part series the shortcomings of the WARN Act and its failures to protect not only the men and women who’d worked at National Machinery Company but displaced workers nationwide.

That this series of stories took nearly three years from assignment to publication is testament to the kind of resource-related challenges confronted by newsrooms, even by ones as dedicated as ours to investigative efforts. During those intervening years, labor disputes arose at The Blade, investigative reporting colleagues departed, and a huge watchdog story broke in our backyard stretching our depleted ranks even thinner. Now, my role with The Blade is evolving as the paper’s only remaining investigative reporter. These days I am paired with beat reporters on projects of varying length and scope to expose them to investigative reporting as we try to keep alive The Blade’s reputation as the public’s watchdog.

To report this story initially, I shuttled between rural Tiffin, Ohio, and Toledo, about a 50-minute drive. In Tiffin, I pieced together the history of National Machinery Company and the lineage of the Frost-Kalnow family, which owned the company for most of the 20th century. I met with groups of National Machinery Company employees so I could chronicle their stories and learn what transpired in the days after Christmas 2001, and later in 2002, when the company reopened as National Machinery LLC. Former employees told stories of lives changed overnight. For some, it had taken years to find new jobs; others never returned to work. A gripping story began to emerge of what it’s like when hundreds of dedicated workers from a community’s dominant employer suddenly have no jobs and no paychecks.

Next, I needed to figure out how the WARN Act failed these people. So I started to review thousands of pages of legal documents and depositions. As I did it became clear that this law—intended to help such workers—was of little use to them or other workers who were confronting this same circumstance. I had already found dozens of examples of employers nationally skirting their obligations under the WARN Act with little or no repercussions. This prompted the paper to decide to examine more broadly how often workers had been ill served by the WARN Act.

Expanding the Investigation’s Focus

Early in the spring of 2005, just as the National Machinery investigation was picking up steam, another Blade investigation took off. On April 3, 2005, reporters James Drew and Mike Wilkinson wrote the initial stories about Toledo-area rare coin dealer Tom Noe, a political insider who managed a $50 million rare-coin fund for the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation. Within two weeks, there was an onslaught of attention on the story—known soon as “Coingate”—and this caused The Blade to expand its “coin team” to include Christopher Kirkpatrick and me.RELATED ARTICLE

See "Investigative Talent Departs After Awards Come In" for more about The Blade's Coingate investigation »For two nearly two years, and as our team grew to six reporters, we tirelessly investigated Ohio state government, triggering a state and federal probe that led to 19 criminal convictions, including Ohio Governor Bob Taft on ethics charges. In November 2006, a judge sentenced Noe, a top contributor of the governor and President Bush, to 18 years in prison for stealing millions of dollars from the coin fund. As Coingate ballooned, my National Machinery files sat untouched. It wasn’t until early 2007, as Coingate drew to a close, that the files were opened again.

At that point James Drew, who worked with me on The Blade’s investigative unit, joined me on this story, and we picked up where I’d left off—starting to examine in-depth national examples of the failures of the WARN Act. Soon we were in Detroit for a week, working out of the nonprofit Maurice and Jane Sugar Law Center that assists workers in WARN Act lawsuits, where we sifted through the center’s records and correspondence. This gave us a good sense about the number of people affected by this act’s weak provisions.

EDITOR'S NOTE

The House of Representatives passed an overhaul of the WARN Act in 2007, and action in the Senate—where Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama has backed a bill to reform the plant closing notification law—is pending. Combining the center’s records with court documents, we built a database of 226 WARN Act cases nationwide. This is what steered our reporting through the final months of the investigation as these records highlighted for us the many ways that businesses exploited the law’s loopholes to avoid warning workers facing layoffs. We spotlighted loopholes by pairing the information we’d garnered from documents with stories we were hearing from affected workers across the nation, including coal miners in West Virginia, mortgage company employees in Connecticut, and paper cup manufacturers in Illinois. Their stories—like those we’d heard in Tiffin—illuminated how few protections the WARN Act actually provides, and our reporting about this situation spurred legislative initiatives in the U.S. Congress.

Trying a Different Approach

Within months of the publication of our WARN Act series, Drew announced his departure, leaving me as the newspaper’s lone investigative reporter. The rapidly changing circumstances of newspapers in this uncertain time of declining ad revenues and digital demands haven’t permitted The Blade to hire an investigative reporter to fill Drew’s position. Our I-team is no longer a team but a single player. But this has not prevented us from doing watchdog journalism.

In August, The Blade published a four-part series documenting new threats to the doctor-patient relationship, an eight-month investigation that I coauthored with Blade health reporter Julie M. McKinnon. The series was the first under our newsroom’s new strategy of integrating beat reporters into investigative projects. In transforming our approach to investigative reporting, the goal is to train more reporters in our newsroom to perform watchdog journalism so our tradition of investigative reporting holds strong.

Like other newspapers, The Blade is looking for ways to tap alternative sources of financing for costly investigative projects. Earlier this year, I was awarded a World Affairs Journalism Fellowship through the nonprofit Washington-based International Center for Journalists. I will use this fellowship opportunity in the fall to journey halfway around the globe, and from there I will report an investigative story that will be of significant importance to our local readers. When I return, the plans call for me to resume my role as an investigative partner with beat reporters in the newsroom; this time I will work alongside a sports reporter on what promises to be a long-term project. And like the others I’ve done, its roots are likely to burrow deep into our local community.

Steve Eder is projects reporter at The Blade. He was a member of the paper’s “Coingate” reporting team whose coverage won a National Headliner Award, a Gerald Loeb Award, and an Associated Press Managing Editors’ Award. The WARN Act project won first place in investigative reporting from the Inland Press Association.