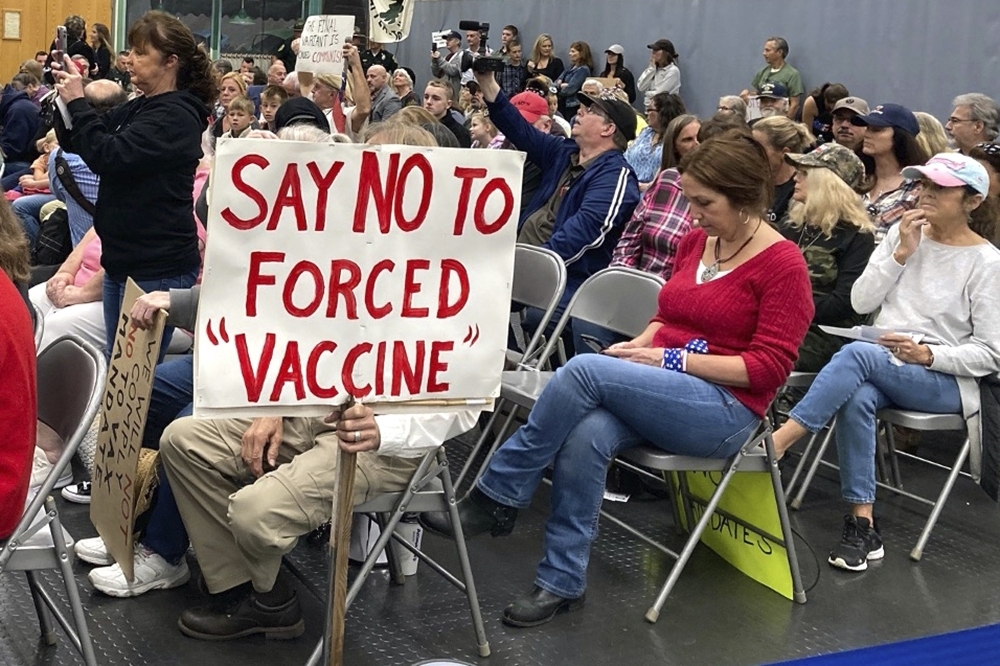

Over the past few years, Americans have become increasingly polarized, having trouble even simply talking to each other and agreeing on basic facts. A 2020 study revealed that the polarization gap — how negatively members of opposing political parties viewed each other — soared by nearly 70 percent.

In this issue, Nieman Reports explores how newsrooms are advancing political coverage that considers voters rather than just vote-seekers, explores divisions without oversimplifying or overstating them, and identifies not only the existence of problems but possible solutions — a practice that in turn makes the reporting more useful and even more accurate.

Stefanie Friedhoff, NF ’01, has launched a new initiative to help address information gaps

Technology has fundamentally changed where people seek information and what they believe. It’s why, no matter how often officials revert to it, communicating by press conference and media interviews alone is no longer sufficient to quickly inform diverse audiences in a crisis and build trust.

Working with public health experts during this pandemic, I realized how easy it is for those of us who have been in journalism for a long time to overestimate what people understand about how our changed information ecosystem shapes the conversation around important issues. While fake news and alternative facts have seeped into the public consciousness, people know less about how underlying design and policy choices allow age-old phenomena like rumors and lies to dominate. This created significant inequities in who has access to accurate, evidence-based information.

That’s why Claire Wardle, founder of First Draft News, and I started the Information Futures Lab (IFL) at the Brown University School of Public Health.

At its core, the Lab is built for individuals and organizations who help people access the information and knowledge they need to live healthy, socially connected lives. From journalists who contextualize news to community organizations that translate issues like changes in abortion rights to public health officials to librarians to educators — the lab equips them with resources, skills, and a network.

How do we do this? By creating rapid learning cycles connecting researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Our team translates into plain language key findings from siloed research fields such as misinformation, behavioral sciences, and the digital humanities. A literature review will launch this fall.

We work directly with practitioners, for example, on evaluating and capturing new ways to build health literacy and misinformation resilience in communities of color hit hard by the pandemic.

We run design sprints, a fellowship program, and a global Community of Infodemics Managers to push for ideation and testing of practices for our new information realities. We think that collectively, we can find out what works long-term to create information spaces that by and large benefit democracy, not threaten it.