Every few years a big news story breaks out from Indian Country. This year it was the tragedy at Red Lake, Minnesota. A few years ago it was the hantavirus epidemic in New Mexico on the Navajo Nation. Or the occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. These are stories that capture the nation’s attention because television news brings us the up-to-date events directly to our living room.

The 1973 siege at Wounded Knee now seems from another era. The TV reporting about the incident was essentially war reporting. There was not even the perception (by TV or print) that an American Indian reporter would or could add perspective. It was an event that just as easily could have been a satellite image from the Middle East or Africa. Anchors, including CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, described the political activism as “Indians on the warpath.”

But pushed by the civil rights movement, the world was changing—even in TV news. In February of 1989 Hattie Kauffman, then working for ABC’s “Good Morning America,” became the first American Indian to report a story for the evening news. The story involved a United Airlines accident. Kauffman happened to be in Hawaii when the story broke and was given the assignment for ABC News.

A few years later, when a mystery illness seemed to be killing young American Indians, the story was reported by more than a dozen Native Americans working for newspapers, local TV and radio stations, and two TV networks. Kauffman was again on the scene, this time representing CBS News. And NBC hired Albuquerque anchor Conroy Chino as a special correspondent.

Patty Talahongva, then a producer for a Phoenix TV station, said she was determined from the start to tell a different version of events. “I made sure from the beginning that it was not a Navajo disease; we never referred to it that way. And we made sure every victim was not a Navajo.” Not all the media were so thoughtful. USA Today coined the phrase “Navajo flu”—a phrase that was easily and often-repeated on TV.

Since that story, however, the number of Native Americans working at the network level has been frozen. When the Red Lake tragedy story unfolded in April, CBS News sent Hattie Kauffman. Unlike many reporters, she had access to tribal officials and was able to fully report the story. But she was the only one telling the story to a national TV audience from a Native American perspective.

Think of that: A generation of one. Hattie Kauffman was the one and only TV network news reporter in 1989. And the same is true in 2005.

There has been a little progress, some hiring of reporters and even anchors in markets from Oklahoma City to Phoenix. But no dramatic change has occurred at either local stations or at the network level. Recent data from Ball State University and the Radio-Television News Directors Association shows Native Americans comprise only three-tenths of one percent of those working in broadcast media.

CNN demonstrated the invisibility of Natives in TV news in June when it announced $1 million in minority journalism scholarships. The money was awarded to the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, the National Association of Black Journalists, and the Asian American Journalists Association. The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) was not included.

“We appreciate CNN’s support for our upcoming convention and their pledge of continued support, and we know our Unity partners will do great things with the money they’ve received. But it’s hard not to be disappointed when the rest of our Unity partners are recognized in this way and we are not,” NAJA’s then-President Dan Lewerenz (Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska) said. “Native people are the most underrepresented of all minorities in national network news. I don’t know of a single Native person currently working in news production for CNN. And many of our students attend colleges that don’t have formal journalism programs or television training opportunities. CNN could have taken tremendous strides toward correcting these imbalances but chose not to. That’s what makes this particularly painful.”

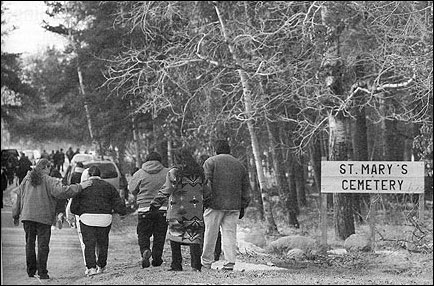

Tribal members walk to the cemetery on the Red Lake Indian Reservation for the burial of the first two victims of the school shootings. March 2005. Photo by Ken Blackbird/The Associated Press.

The Value of New Voices

What will it take to do better? It’s unlikely there will be any improvement until TV news recognizes the depth of the problem. Three-tenths of a percent ought to be painful to news executives, too. “If the broadcast news industry takes seriously its commitment to diversity, then we need to see these numbers turn around,” Lewerenz said. “That’s going to require outreach to both high school and college students. It’s going to require looking beyond the established journalism schools and finding innovative ways to train journalists outside the curriculum. It’s going to require paid internships, so that students aren’t forced to choose between earning work experience and paying for college.”

It’s tempting to dismiss diversity in the broadcast news media as impossible to achieve, to give up on reaching the goal—or perhaps focus on other media. But here’s another story, a hopeful one. A few years ago, Eugene Tapahe was offered an internship at the sports cable network ESPN. Tapahe, then 33, worked at his tribal newspaper, the Navajo Times, but he was eager to try something new and accepted the internship. Once he started, Tapahe was surprised to learn that ESPN had never aired a story about American Indian symbols and names being used as franchise mascots.

So Tapahe pitched the story, researched the topic, and waited. A day went by, then a week. He asked a producer what was up, only to be told that his material had not yet been read. But Tapahe wouldn’t quit. He knew he had good stuff and wanted the producers to go forward, or to just tell him to forget the idea. Finally he marched into a senior producer’s office and made his pitch in person.

His courage and determination paid off. The story was assigned, and the project was a go. Perhaps it’s significant that Tapahe did not play a major role in developing the story that eventually aired. He was, after all, an intern. But he helped create an environment of journalistic respect in which reporters and producers went about telling a story in a different way. Tapahe says he’s proud of the story that eventually aired.

Indian Country is full of such stories, ones that ought to be told with respect. There are complicated histories that defy traditional grab-and-go journalism—stories with roots deep in history. They are stories about nations whose governments predated those of the United States, stories about cultures, languages and people. Native Americans deserve to be among those who decide and report those news stories—and others—to a TV audience. The talent is there; it’s just not visible. How invisible? Well, 99.7 percent makes what little presence there might be very close to being completely invisible.

Mark Trahant is the editorial page editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He is a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe and author of “Pictures of Our Nobler Selves: A History of Native American Contributions to News Media,” published by The Freedom Forum First Amendment Center, 1995.

The 1973 siege at Wounded Knee now seems from another era. The TV reporting about the incident was essentially war reporting. There was not even the perception (by TV or print) that an American Indian reporter would or could add perspective. It was an event that just as easily could have been a satellite image from the Middle East or Africa. Anchors, including CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, described the political activism as “Indians on the warpath.”

But pushed by the civil rights movement, the world was changing—even in TV news. In February of 1989 Hattie Kauffman, then working for ABC’s “Good Morning America,” became the first American Indian to report a story for the evening news. The story involved a United Airlines accident. Kauffman happened to be in Hawaii when the story broke and was given the assignment for ABC News.

A few years later, when a mystery illness seemed to be killing young American Indians, the story was reported by more than a dozen Native Americans working for newspapers, local TV and radio stations, and two TV networks. Kauffman was again on the scene, this time representing CBS News. And NBC hired Albuquerque anchor Conroy Chino as a special correspondent.

Patty Talahongva, then a producer for a Phoenix TV station, said she was determined from the start to tell a different version of events. “I made sure from the beginning that it was not a Navajo disease; we never referred to it that way. And we made sure every victim was not a Navajo.” Not all the media were so thoughtful. USA Today coined the phrase “Navajo flu”—a phrase that was easily and often-repeated on TV.

Since that story, however, the number of Native Americans working at the network level has been frozen. When the Red Lake tragedy story unfolded in April, CBS News sent Hattie Kauffman. Unlike many reporters, she had access to tribal officials and was able to fully report the story. But she was the only one telling the story to a national TV audience from a Native American perspective.

Think of that: A generation of one. Hattie Kauffman was the one and only TV network news reporter in 1989. And the same is true in 2005.

There has been a little progress, some hiring of reporters and even anchors in markets from Oklahoma City to Phoenix. But no dramatic change has occurred at either local stations or at the network level. Recent data from Ball State University and the Radio-Television News Directors Association shows Native Americans comprise only three-tenths of one percent of those working in broadcast media.

CNN demonstrated the invisibility of Natives in TV news in June when it announced $1 million in minority journalism scholarships. The money was awarded to the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, the National Association of Black Journalists, and the Asian American Journalists Association. The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) was not included.

“We appreciate CNN’s support for our upcoming convention and their pledge of continued support, and we know our Unity partners will do great things with the money they’ve received. But it’s hard not to be disappointed when the rest of our Unity partners are recognized in this way and we are not,” NAJA’s then-President Dan Lewerenz (Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska) said. “Native people are the most underrepresented of all minorities in national network news. I don’t know of a single Native person currently working in news production for CNN. And many of our students attend colleges that don’t have formal journalism programs or television training opportunities. CNN could have taken tremendous strides toward correcting these imbalances but chose not to. That’s what makes this particularly painful.”

Tribal members walk to the cemetery on the Red Lake Indian Reservation for the burial of the first two victims of the school shootings. March 2005. Photo by Ken Blackbird/The Associated Press.

The Value of New Voices

What will it take to do better? It’s unlikely there will be any improvement until TV news recognizes the depth of the problem. Three-tenths of a percent ought to be painful to news executives, too. “If the broadcast news industry takes seriously its commitment to diversity, then we need to see these numbers turn around,” Lewerenz said. “That’s going to require outreach to both high school and college students. It’s going to require looking beyond the established journalism schools and finding innovative ways to train journalists outside the curriculum. It’s going to require paid internships, so that students aren’t forced to choose between earning work experience and paying for college.”

It’s tempting to dismiss diversity in the broadcast news media as impossible to achieve, to give up on reaching the goal—or perhaps focus on other media. But here’s another story, a hopeful one. A few years ago, Eugene Tapahe was offered an internship at the sports cable network ESPN. Tapahe, then 33, worked at his tribal newspaper, the Navajo Times, but he was eager to try something new and accepted the internship. Once he started, Tapahe was surprised to learn that ESPN had never aired a story about American Indian symbols and names being used as franchise mascots.

So Tapahe pitched the story, researched the topic, and waited. A day went by, then a week. He asked a producer what was up, only to be told that his material had not yet been read. But Tapahe wouldn’t quit. He knew he had good stuff and wanted the producers to go forward, or to just tell him to forget the idea. Finally he marched into a senior producer’s office and made his pitch in person.

His courage and determination paid off. The story was assigned, and the project was a go. Perhaps it’s significant that Tapahe did not play a major role in developing the story that eventually aired. He was, after all, an intern. But he helped create an environment of journalistic respect in which reporters and producers went about telling a story in a different way. Tapahe says he’s proud of the story that eventually aired.

Indian Country is full of such stories, ones that ought to be told with respect. There are complicated histories that defy traditional grab-and-go journalism—stories with roots deep in history. They are stories about nations whose governments predated those of the United States, stories about cultures, languages and people. Native Americans deserve to be among those who decide and report those news stories—and others—to a TV audience. The talent is there; it’s just not visible. How invisible? Well, 99.7 percent makes what little presence there might be very close to being completely invisible.

Mark Trahant is the editorial page editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He is a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe and author of “Pictures of Our Nobler Selves: A History of Native American Contributions to News Media,” published by The Freedom Forum First Amendment Center, 1995.